Emerging Markets Contagion? Maybe. Crisis? No.

Will the turmoil in Turkey will morph into some sort of global contagion that takes down financial markets? Nah

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Emerging-market equities and currencies as measured by MSCI indexes both fell on Monday to their lowest levels since July 2017, and everyone wants to know whether the turmoil in Turkey will morph into some sort of global contagion that takes down financial markets. If you think of contagion as some sort of event that causes a broad repricing of financial assets, then, yes, contagion is a possibility. But a full-blown crisis? It’s too early to say, judging by the markets.

Besides Turkey, plenty of sizable markets are under severe pressure: South Africa, Russia, India, Brazil and even China could be included in that group. The MSCI EM Index of equities is down 18.2 percent from its peak on Jan. 26, while its sister currency gauge has dropped 8.14 percent since early April. What often gets lost in the discussion about emerging markets is that while it’s true they probably borrowed too much as major central banks slashed interest rates to zero after the financial crisis, their economies are in pretty good shape. Foreign-exchange reserves for the 12 largest EM economies excluding China stand at $3.15 trillion, rising from less than $2 trillion in 2009, data compiled by Bloomberg show. Outside of China and Turkey, current-account deficits have turned into surpluses since 2016 despite tighter funding conditions because of higher U.S. interest rates, according to Bloomberg News’s Netty Ismail and Filipe Pacheco. “There aren’t really any other emerging markets that have exactly the same toxic blend that Turkey has,” Paul McNamara, a London-based fund manager at GAM UK Ltd., told Bloomberg Television. “Only Argentina really has the external deficit, and they don’t have as much domestic debt.”

Some traditional measures of market stresses would seem to back up McNamara’s assertion. The so-called Ted Spread, or difference between the three-month London Interbank Offered Rate for dollars and similar maturity Treasury bills, has dropped to 0.28 percentage point from 0.64 point in April. The difference between Libor and overnight index swap rates has dropped by a similar amount as well. And finally, despite the worry about the exposure of banks to Turkey and a drop in their share prices, a measure of expected short-term bank funding costs has dropped to its lowest since February.

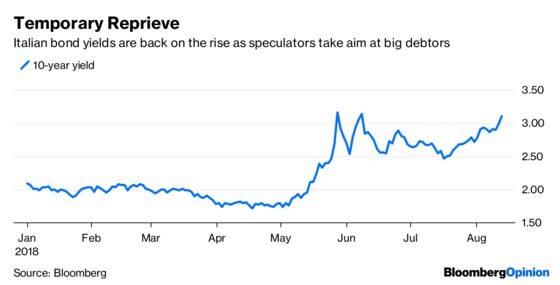

ITALY IS WORTH WORRYING ABOUT

If you’re looking for a market to worry about, check out Italy. Its bonds tumbled in May when a new populist government raised doubts about the country’s continuing membership in the European Union. The rhetoric died down for a while as officials signaled that they were willing to play nice with the rest of the EU. But now the nation’s bonds are back on the decline, with yields on Italian 10-year notes rising on Monday to 2.77 percentage points above those on similar maturity German bunds, the widest gap since the May concerns. With $2.5 trillion in government debt, Italy is tied with France as the world’s fourth-most indebted nation after the U.S., China and Japan. So why aren’t the broader measures of market stresses also panicking about Italy? The answer is probably because central banks — especially the European Central Bank — have proved time and again that they are willing to step in and provide as much money as it takes to prevent another financial crisis. Investors know that’s something Claudio Borghi, the head of the budget committee in Italy’s lower house, probably realizes. He said in an interview with Bloomberg News on Monday that the ECB should keep providing a shield to the government securities of all monetary union members to avoid a dismantlement of the entire euro system. “There cannot be a system at the mercy of market movements,” Borghi said.

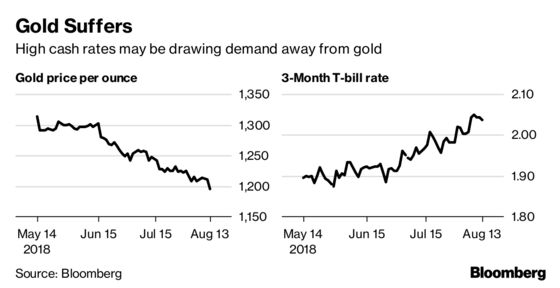

GOLD LOSES ITS LUSTER

Surely gold, a traditional market haven, is seeing demand, right? Wrong. The price of the precious metal dipped below $1,200 an ounce on Monday for the first time in 18 months. As recently as April, the price of gold was above $1,350 an ounce. Investors and strategists like to tie gold’s weakness to the strength of the dollar. That is because gold is traded in greenbacks and any increase in the currency’s value makes buying gold that much more expensive. There’s certainly some truth to that, with the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index rising on Monday to its highest level since June 2017. But more is going on to suggest that gold’s decline is far from over. For the first time in more than a decade, gold has some strong competition from cash for the attention of haven-seeking investors. Three-month Treasury bill rates are above 2 percent for the first time since mid-2008. They were about 1 percent less than a year ago and virtually zero from 2009 through 2015. Those higher rates are drawing international investors to the dollar, helping to boost the greenback. Money managers are making a big bet that gold prices will continue to decline. In the week ended Aug. 7, money managers expanded their net-short position, or the difference between bets on a price increase and wagers on a decline, by 54 percent to 63,282 futures and options, according to Commodity Futures Trading Commission data, according to Bloomberg News’s Joe Deaux. That’s the biggest bearish bet since the data began in 2006.

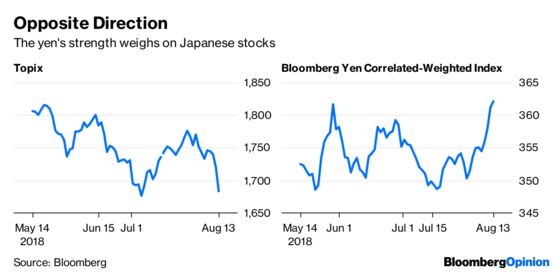

THE YEN'S A WORLDBEATER

One traditional measure of market concern is acting appropriately. The yen, which gained on Monday, is the only one of 31 major currencies tracked by Bloomberg to appreciate against the dollar this month, rising just more than 1 percent. A Bloomberg Correlated-Weighted Index of the yen against its developed-market peers puts the currency at its strongest level since April 2017. Japan’s healthy current-account surplus means it’s one of the few major economies that isn’t depending on outside capital to fund itself. Also, many investors take out low-cost loans in yen and use the money to invest elsewhere in the world where rates are much higher. In times of “risk off” environment, like now, investors typically reverse those bets, creating demand for yen so they can pay off the loans. This strength in the yen is largely unwelcome in Japan, which desires a weaker currency to boost exports in an economy only forecast to expand about 1 percent this year. As such, yen strength was a main reason the benchmark Topix index of equities tumbled as much as 2.23 percent Monday, the most since March. The Topix has dropped 7.4 percent in 2018 for the worst performance among developed equity markets tracked by Bloomberg. The Topix trades at 13 times estimated earnings, the lowest level since July 2016. The S&P 500 Index in the U.S. is valued at 17.6 times expected profits.

STOCK PREMIUMS RETHOUGHT

U.S. stocks haven’t sidestepped the sell-off in global equities, with the S&P 500 Index falling on Monday for the fourth consecutive day. That’s the longest slump since March. Although at 1.28 percent, the declines over the last four trading days are much less than the 2.98 percent drop in the MSCI All-Country World Index excluding the U.S., the weakness may indicate that investors are questioning how much they’re willing to pay to be in U.S. equities. The S&P 500’s 12-month forward price-to-earnings ratio of about 17.5 compares with about 13.3 for the MSCI index excluding the U.S. Such a heady premium for U.S. equities is largely predicated on the recent strength in America’s economy continuing, but the U.S. government isn’t even sure that will be the case. The Congressional Budget Office slightly lowered its forecast for U.S. economic growth for this year and warned of increasing uncertainty from the Trump administration’s plans to widen tariffs. The U.S. economy is projected to expand 3.1 percent this year, down from a previous forecast in April of 3.3 percent, the nonpartisan group said in a report on Monday. The expansion will ease to 2.4 percent in 2019, unchanged from April’s projection, on slowing growth in business investment and government purchases, the CBO said.

TEA LEAVES

It’s a big week for economic data in China, and the first round of reports weren’t so great. China’s broadest measure of new credit slowed, underlining concerns about the economy that have prompted authorities to start doing more to support growth, according to Bloomberg News. Next up on Tuesday is industrial production, with the median estimate of economists surveyed by Bloomberg calling for a tick up to 6.3 percent annual growth for July from 6 percent in June after robust exports. Also, retail sales are seen increasing 9.1 percent, after a 9 percent jump in June. Chief Economist Tom Orlik wrote in a Saturday note that the view of Bloomberg Economics is that with headwinds to expansion blowing from home and abroad, a tilt toward pro-growth policies carries more pluses than minuses.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.