(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Ten years on from the financial crisis, bank balance sheets haven’t become any simpler to digest for the average investor. Finance firms are big and leveraged; regulations have just become new instruments of complexity. That might suggest a potential windfall for any brainy number-cruncher who’s bored enough to spend a year looking for inconsistencies in the industry’s accounts.

London hedge fund Caius Capital certainly thinks so. It carved out a niche for itself in 2017 when it accused Britain’s mighty West Bromwich Building Society – 750 employees, 9 million pounds ($12 million) in profit – of wrongly classifying debt instruments as core capital. Not exactly the stuff of a Michael Lewis thriller, but it kind of worked. The Midlands firm bought back the instruments before the regulator had made a final judgment on the case. Caius made money.

The limits of this strategy were exposed, though, after Caius went after a much bigger fish. In May, the hedge fund accused Italian bank UniCredit Spa of wrongly classifying hybrid securities as core capital. This time, Caius was shot down by Europe’s banking regulator. UniCredit is now suing the hedge fund for damages. It’s hard to say what the average market participant has gained.

The UniCredit case centers around 2.4 billion euros of instruments, which the bank has counted towards its closely-watched core capital ratio since 2011. These have a share component, but also a fixed-dividend component via payouts on those shares, which make them similar to debt. Caius argued that under more recent banking rules, they shouldn’t be defined as core capital, and some kind of conversion or buyback was needed. To the hedge fund’s benefit, of course.

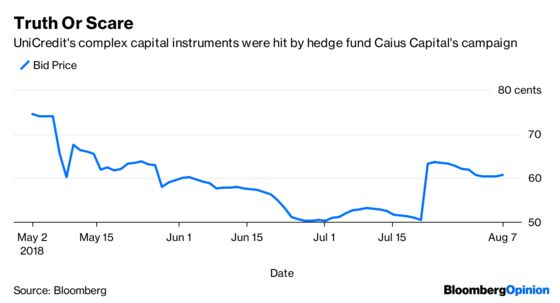

The episode does reveal one useful thing. When an attack like this is launched, the market clearly has trouble working out whether it has any merit. The bonds in question dropped, and kept dropping, as even sophisticated analysts were unable to categorically rule out an upholding of the claim by the regulator.

Indeed, even after the European Banking Authority ruled that there wasn’t enough evidence to uphold the Caius thesis, the bonds are still not back to April’s 75-euro cent levels – although they have recovered to about 60 euro cents, from lows around the 50 euro cent mark.

But there are obvious problems with the Caius approach. It clearly over-reached, and not in a responsible way. It didn’t just question these specific instruments, but explicitly cast doubt on the entirety of UniCredit’s capital base. That probably explains why the bank’s CEO Jean Pierre Mustier – with experience of both the 2008 meltdown and the euro-zone debt crisis – is insisting on a counter-strike. Bank runs are unpredictable things, and the wrong headline on a wrong day may cause just that.

For its part, Caius insists there are holes in the EBA’s response. But its inability to convince the regulator shows the potential danger of such campaigns. If neither the bank nor its supervisor blinks, it becomes harder to view these hedge fund strategies as serving a wider purpose for an efficient market. Rather, it just risks creating liquidity shocks in specific situations. Hardly the ideal of the ethical short.

Caius will doubtless keep railing against bank balance sheets, and UniCredit will pursue its claim for redress. But for that poor average investor, it would all be far easier if regulators made bank balance sheets understandable for mere mortals.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering finance and markets. He previously worked at Reuters and Forbes.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.