(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The answer to one of Mario Draghi’s problems lies in a dusty corner of a basement gym.

Though the European Central Bank is ending new net bond purchases through quantitative easing, its stimulus packages are still very much under discussion. One issue concerns the maturities it will target when it reinvests its substantial slug of maturing debt and coupon payments — should these go short, or long? This choice poses a dilemma, and resolving it may be a matter of crushing it with a barbell.

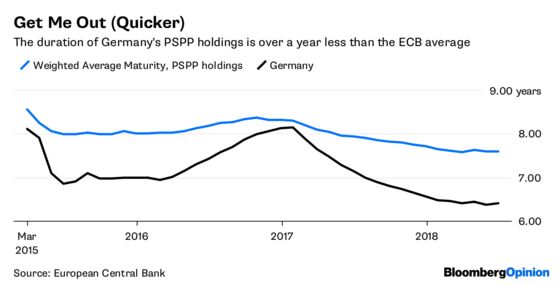

There’s a lot of merit in plowing redemptions into short-dated government debt. As I’ve argued, that would shorten the duration of the ECB’s stock of purchases, paving the way for the ECB to be fully out of the program sooner. Core European countries such as Germany and the Netherlands have been wanting this for ages.

But it would be a stealth tightening move. The bank has been worried about the portfolio’s duration shelving off for some time. ECB Chief Economist Peter Praet said in a speech on Oct. 2 that as time passes the loss of duration in the bank’s portfolio is “bound to exert increasing upward pressure on the term premium.” That’s higher long-end yields to you and me.

For the bloc’s economic laggards, such as Italy, that would be a really unwelcome development. But the alternative — focusing redemptions on very long-dated bonds to bring down yields — would be too much for the core nations to swallow.

The recent pattern of purchases have been focused around 5-10 years and produced an average duration of 7.6 years. Continuing probably means duration would continue to drift lower — that’s Praet’s point.

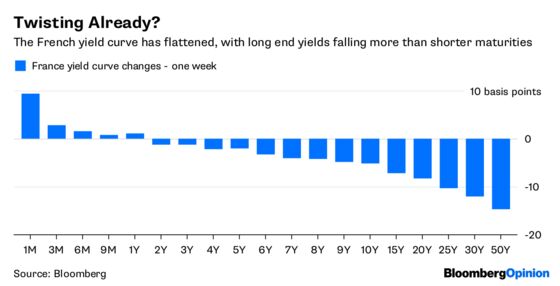

Talk of ultra-long buying has already had an impact. The yield differential between 10-year and 30-year French bonds decreased 10 basis points in the past week.

An alternative to the above would be for the ECB to use funds from maturing German debt and coupon payments to buy debt of weaker countries, possibly at the very long end. But that looks like a step too close to fiscal transfers, and the Bundesbank has already pushed back, insisting that officials must stick to the capital key, a guideline for bond purchases that’s linked to the size of member nations’ economies. That seems an outright veto.

Board member Joachim Wuermeling has said the Bundesbank must also insist on market neutrality — meaning, no dramatic change to duration. This sounds more like an objection than a veto. Some skillful negotiation could bring Germany’s central bank around.

And it might accept one way to solve the dilemma. The remedy could be a time-lagged barbell. From now until the end of QE, purchases could focus on one-year debt. As these mature they’d bolster the pool of funds the ECB can spend. By late 2019, the bank may have serious extra firepower to start buying securities as long as 31 years.

In the very near term, this would drag down the average duration of the ECB’s portfolio. But that wouldn’t have to last. Weaponizing this war chest could give officials almost as much control over the yield curve as they had through the flow of purchases. This would be enhanced were they to extend the time frame for their redemptions policy.

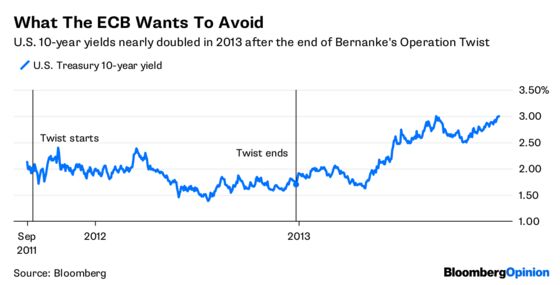

Central banks’ experiments with controlling the yield curve in recent years have produced mixed results. The Federal Reserve’s Operation Twist in 2011 didn’t necessarily live up to expectations, and Chairman Ben Bernanke reverted back to regular QE in little more than a year.

Japan has had remarkable success with its Yield Curve Control program, which fixes 10-year yields at or close to zero. The ECB must be eying this result with envy.

The ECB could have the power to retain as much control over the bond market in the countries it needs to for many years to come, even though it will no longer be making new net purchases. Having bought more than 2 trillion euros ($2.3 trillion) of government bonds over the last three years to rescue the European economy, officials would be foolish not to do everything they can to maintain the potency of their efforts — and Draghi could take an opportunity to secure his legacy.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jennifer Ryan at jryan13@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.