Novartis Goes Back to Its $191 Billion Core

Novartis’s new boss has picked the low-hanging fruit. Now he needs to get on with running it as a drugmaker.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Novartis AG’s former CEO Daniel Vasella made a mistake when he bought into the eyecare provider Alcon back in 2008. Joe Jimenez, his successor at the Swiss drug giant, acknowledged as much by launching a review of the business early last year.

Now, Jimenez’s own replacement, Vas Narasimhan, is taking decisive steps to move on by arranging the unit’s demerger. Narasimhan is quickly shaking off the baggage he inherited from his two predecessors. We’ll now see what he really wants to do with this $191 billion company.

He’s had some luck so far. He started in February, just before Novartis gained the right to sell out of its consumer healthcare joint venture with GlaxoSmithKline Plc. He seized his chance, raising $13 billion in the process at a pretty punchy multiple of the unit’s profit. With $8.7 billion of the proceeds, Narasimhan bought AveXis Inc., a promising biotech that isn’t generating any earnings yet.

In fairness to Jimenez, the decisions on getting rid of Alcon and the consumer health business were a gift to the new boss. There’s no convincing argument for keeping Alcon. After a long period of ownership, the synergies with the rest of Novartis are negligible. Investors buy big pharmaceuticals companies in the hope of seeing a high-margin blockbuster drug. By contrast, progress in the kind of medical technology offered by Alcon is more gradual. Profitability is lower too: Alcon is a drag on margins.

The only question was the mechanism for separation. Other big drug companies wouldn’t want to own Alcon either. The asset, valued by Vontobel analysts at $15-$23 billion, is probably too big a mouthful for private equity. An initial public offering would mean wading through red tape by issuing a prospectus to new investors, while only selling a minority stake. That would raise relatively paltry proceeds for such a large company. A demerger is a tax efficient way of finding new investors who actually want to own medical technology.

While Narasimhan looks like a man in a hurry given all he has done in his five months in charge, these moves were expected. He’s fortunate too that he can use the remaining proceeds from the GSK deal on a $5 billion share buyback. That will lift earnings per share, providing a counter-balance to the reduction in earnings from offloading the consumer and eyecare businesses — useful when recent acquisitions will take time to start delivering.

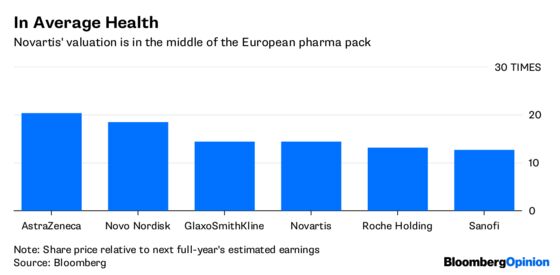

Narasimhan is making the most of his inheritance. Novartis can now focus on drug discovery. It has a relatively strong pipeline, which means it doesn’t have as much need to buy expensive biotechs as some of its peers. But there is a strong balance sheet to take advantage of any opportunities that arise. After taking all the low-hanging fruit, the new CEO now needs to get on with running the company as a drugmaker.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.