(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The Labour Party’s plan to oblige the Bank of England to pursue a productivity target alongside its current inflation objective has been widely derided. But it has ambitions to press-gang the central bank into supporting its statist objectives that go much further, are potentially more damaging to the economy, and threaten to undermine the institution’s independence.

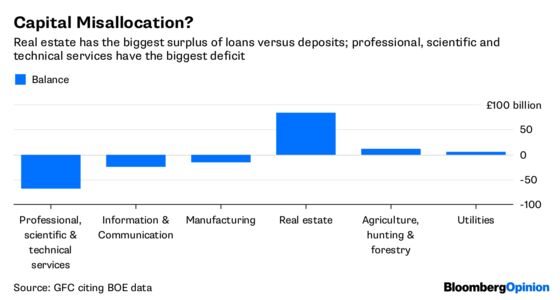

The aim is to co-opt the central bank into using its regulatory muscle to steer commercial bank lending into areas of the economy that the party deems beneficial to boosting productivity, like manufacturing, and away from sectors it finds objectionable, namely residential and commercial real estate. If this reeks of central planning, it’s because it is.

“Monetary policy, macroprudential policy and the government’s industrial strategy need to be integrated,” the report says. “The Bank of England will need to use credit guidance to influence the flow of credit both quantitatively and qualitatively.” If Labour is elected, it should widen the central bank’s responsibilities to include boosting “private sector investment into critical areas of technology.”

But U.K. Finance, a trade association representing the finance and banking industry, said this week that lending to manufacturers has expanded by 5.1 percent in the past six months, compared with a 2.5 percent contraction in total borrowing by U.K. businesses. So the idea that banks aren’t lending to manufacturing is false.

One of the wackier proposals is that banks should be obliged to reduce their reliance on real estate as collateral for loans. “Banks will be required to show they are raising the share of loans backed by intellectual property instead,” the report says. If assessing the value of bricks and mortar is difficult, it’s a walk in the park compared with trying to gauge how much a patent or an innovative manufacturing process could be worth.

There’s also a hint of how quantitative easing would be used in the future. The Bank of England halted its corporate bond purchases earlier this year, having bought 10 billion pounds ($13 billion) of debt. The program, according to the white paper, “missed a chance to influence the cost of borrowing for companies that will contribute more to raising the potential growth path of the economy.”

That suggests that under a Labour government, any new QE program would be steered toward purchasing the debt of companies deemed to be aligned with the government’s industrial strategy, begging the question as to which industries would be favored and which would be shunned.

Moreover, Labour is rubbing its hands at the prospect of having its own state-controlled bank to enforce its policies. The government has a 62 percent stake in Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc, after bailing it out during the financial crisis.

Labour’s plan envisages creating a Strategic Investment Board which would “provide direction for the Bank of England in respect of credit guidance,” as well as a National Investment Bank which would direct lending through RBS.

“Business relationship managers at the Royal Bank of Scotland would need to target small- and medium-sized enterprises, helping the development of their businesses,” the white paper says. “Banks haven’t done enough to support companies in sectors that are critical to raising the productive potential of the U.K. economy. Credit guidance is a new policy tool for the Bank of England designed to correct this flaw with monetary policy.”

Ewen Stevenson, once tipped as a future CEO of RBS, must be breathing a sigh of relief. He stepped down as RBS’s chief financial officer last month before taking up the same job at HSBC Holdings Plc. Rising to the top of one of banking’s greasy poles looks far less attractive if the institution you hoped to head has to kowtow to the government’s interventionist policies.

The idea that the government knows which industries should be rewarded with access to capital and which should be starved of investment is straight out of the central planning handbook, which went out of print in capitalist economies decades ago. It beggars belief that Labour reckons it knows best when it comes to allocating loans across the economy.

It was Labour that won over financial markets by granting the Bank of England independence over monetary policy back in May 1997. Its newfound enthusiasm for dragooning the institution into executing its efforts to steer commercial bank loans this way and that will be much less welcomed by investors if Labour wins power in what will already be a troubled post-Brexit economy.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.