There’s No Brexit Dividend. Nobody Cares.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Each side of the U.K.'s 2016 Brexit debate peddled an economic narrative. Remainers warned of big economic costs from leaving the European Union. Leavers promised Brexit dividends: budget savings to be spent on the National Health Service, freedom from red tape, "frictionless" EU trade and a host of new trade deals that would be a boon to exporters.

These days, it's becoming clear which side was selling snake oil. And yet, those who sold the Brexit-dividend narrative are doubling down on that bet. Those who assumed that economic reality would force Brexiters to retreat from their demands of a harsh break with the EU have been mistaken.

Evidence of economic pain has been steadily piling up. Growth has slowed dramatically, wages are stagnant and households are not spending near what they would have been expected to spend had the Brexit referendum failed two years ago.

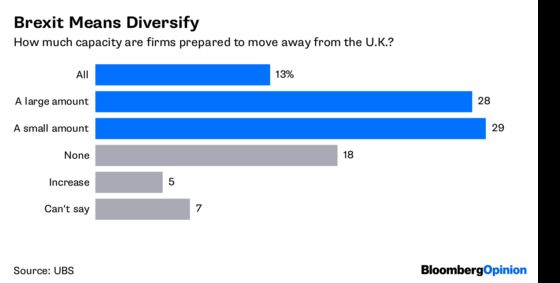

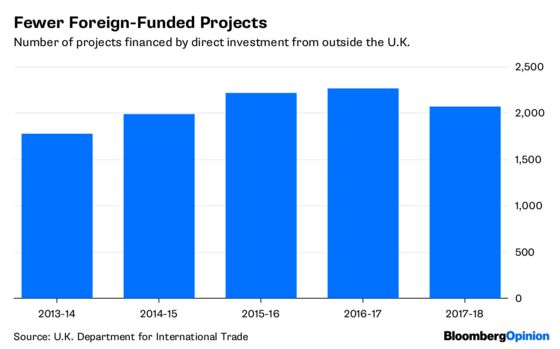

A boon for the U.K. economy? European companies are cutting investments in the U.K. A recent survey from UBS of 600 firms suggests that 35 percent of companies plan to reduce their investment in the country after it leaves the EU; 41 percent plan to move a large amount of capacity out of the U.K. entirely and 42 percent plan to shift that to the euro zone.

Last week Airbus — which employs 14,000 workers in the U.K. and supports another 110,000 jobs through its supply chain — put the government on notice that it would pack up if the government can't reach a deal for a new trading relationship with the EU, the very "no deal" option that Prime Minister Theresa May insists it must preserve for negotiations to be successful. Other big U.K. employers issued similar warnings.

Brexiters cling to the much-ridiculed promise of a 350 million pound ($460 million) weekly windfall that would supposedly arrive when payments to the EU stop, and that could be used to finance the troubled NHS. A week ago, Theresa May promised an extra 20 billion pounds of spending on health care, but it was quickly clear that this would not come from any Brexit-related savings; it would either come from cuts elsewhere, more borrowing or new taxes, and probably all three.

There is no sign of new free-trade deals to follow or any regulatory overhaul that would turn the U.K. into a Singapore-on-the-Thames. There is no chance that the EU will grant May the full control she wants as well as the access to EU markets she's asking for, especially for financial services. Brexit is only the fourth most important item to be discussed at the European summit Thursday and Friday.

Logic might seem to dictate that, at this point, more people should want to call the whole thing off. But far from accepting the Remain case on the economy, the latest troubles have caused Brexiters to dig in, point the finger at business for stoking fears and accuse Remainers of being pessimistic and impatient. Chief Leaver Jacob-Rees-Mogg has dismissed businesses that warn of the costs of Brexiting with "wanting to suck up to the Treasury," the ministry that Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson derided as the "heart of Remain."

As psychologists of decision-making have found, emotional signals trump objective information for voters. This is evident in attitudes toward immigration, which remain instinctively hostile despite a dramatic drop-off in European migration and skills shortages in parts of the economy, including the health service and technology sectors.

Remainers (some 100,000 demonstrated in London last weekend) point to shifts in public opinion and hope their arguments are holding more sway. It's true that if you ask people whether they thought the vote was right or wrong, more people now say it was wrong. But it's far from clear how a second vote would go, or even what the question would be. And it seems that the shift that's being observed has more to do with those who didn't vote for Brexit now taking a skeptical view, than Leavers actually changing sides.

Britain is thus caught in a vicious circle. The factors that created Brexit are only being worsened by Brexit, but as the pain grows, it brings more criticism of the establishment, business and other perceived enemies. Brexiters don't blame Brexit. That will make it hard for any government to make decisions that fuel growth and investment.

Leading Brexiters like Rees-Mogg and Johnson are betting that there will be economic gains once the dust has settled. But they understand that for Brexit voters — those whom they hope will elect the next Conservative government — the real dividend is already here. It's emotional satisfaction.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jonathan Landman at jlandman4@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.