OPEC Has Your Back. Feel Better?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The day after OPEC delivered a statement with all the clarity of a White House press briefing, Saudi Arabia’s energy minister went out of his way to clarify one thing: Consumers can count on the group to deliver.

History (and projections) would suggest not to take that at face value.

An old saying about OPEC is that it’s like a tea bag, working best in hot water. The group tends to be quite successful at dealing with painful price crashes by taking oil supply off the market. Capping rallies to help out customers is a different story.

Back at the turn of the century, OPEC was just emerging from a dip in the teapot, having cut supply to resuscitate sub-$10 oil prices. The group foresaw steady growth in global oil demand and big gains in market share. In late 2000, Nigeria, Iran and Venezuela talked of raising their oil output by at least 4.7 million barrels a day that decade, equivalent to creating another Iran and then some.

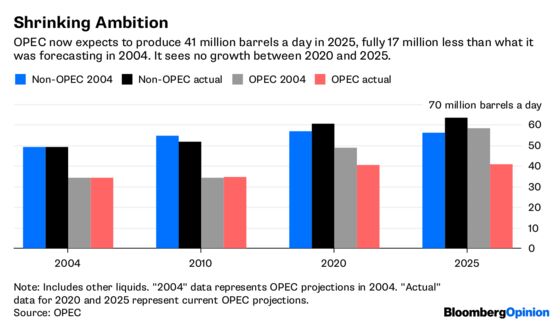

By 2004, oil prices had quadrupled from 1998’s trough and China’s supercycle was revving up — as were OPEC’s ambitions. It forecast global supply rising 27 percent by 2020, to 106 million barrels a day. And OPEC would supply two out of every three of those extra 22 million barrels, taking its market share from 41 percent to 46 percent. By 2025, that was set to rise to 51 percent, power not seen since the energy shocks of the 1970s.

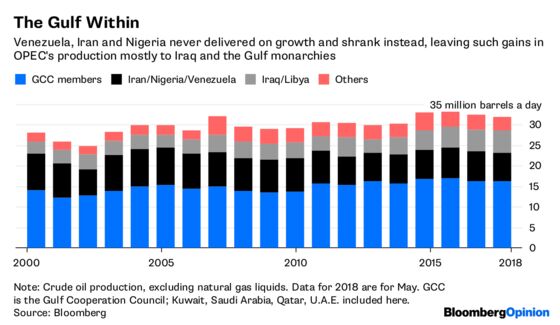

Something didn’t add up, though; namely, OPEC’s internal market shares. The group’s crude oil production increased by almost 2 million barrels a day between 2000 and 2004. Within that, output from Venezuela, Iran and Nigeria rose by a collective … 30,000 barrels a day. In fact, 2004 turned out to be the peak for those three countries this century; by May of this year, they were down to less than 7 million barrels of crude a day, and heading lower. So much for another Iran.

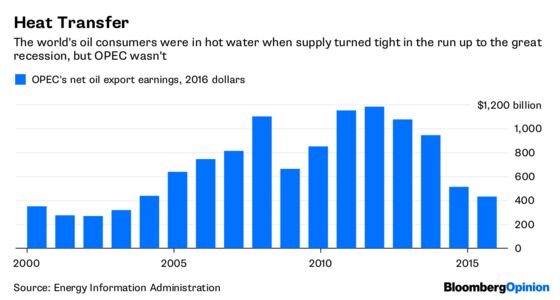

Those missing barrels helped catapult oil into triple digits by 2008, as surging demand ate into virtually all of OPEC’s spare capacity. And one can’t help thinking that a lack of hot water played a part. After all, the price spike meant that, while OPEC’s crude oil output in 2008 was actually slightly lower than in 2004, the group’s net revenue from oil exports jumped 151 percent in real terms:

Similarly, when Libya blew up in 2011, the best OPEC did was to keep its output flat. Oil prices were stable; indeed, implied volatility hits its lowest since the mid-1990s. Problem is, they were stable at $100-plus, providing other OPEC members with the means to boost public and defense spending in order to fend off any Libya-like turmoil.

OPEC did eventually boost production by almost 3 million barrels a day. It’s just that most of it came in 2015, and mostly in an attempt to wrest market share back from rival producers in places like North America, rather than concern for customers. The latter were already voting with their wallets: Demand growth in 2014 was the weakest since the crisis year of 2009.

OPEC’s ambitions of the early 2000s now read like fantasy. Being unable or unwilling to cap rallies brought periodic windfalls. But the cost has been steep, encouraging alternative supplies — including from tight oil, particularly nettlesome for OPEC — conservation, and vehicle-electrification efforts. In other words, the market isn’t as big as was expected, and neither is OPEC’s share of it:

The other price is division. OPEC’s announcement was studiedly obscure to disguise its main point — namely, that the Gulf monarchies such as Saudi Arabia and outside partners such as Russia would step in to supply the extra barrels the likes of Iran and Venezuela could not.

That will keep the market looser through the rest of this year. There’s an obvious long-term problem here, though. The enlarged OPEC-plus group has a combined market share of about 50 percent — just as the old group once dreamed — but corralling a wider set of producers won’t be any easier than with the smaller one.

Absent dramatic turnarounds in the fortunes of countries such as Venezuela, OPEC will be hamstrung in its core mission of keeping the world buying oil (especially its oil), let alone dealing with existential issues like climate change. In an increasingly competitive energy market, reliability counts. OPEC has a dwindling capacity to provide barrels as needed. More importantly, as this latest declaration shows, that need arises mostly from the weakness within its own ranks.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.