(Bloomberg Opinion) -- If this year’s bank stress tests were graded on curve, Wells Fargo & Co. would be at the bottom.

It didn’t fail. No bank did. For the second consecutive year, all of the banks examined were able to survive the Federal Reserve’s hypothetical worst-case economic scenario, according to results of the first round released on Thursday. Next week, the Fed will examine the banks’ own capital plans and approve or reject their proposed dividends and buybacks. That portion of the test, given that the economy is not in a recession, has become more significant than the first round.

But on this portion of the test, nearly 10 years after it was introduced, it’s not clear “passing” is the right benchmark for success. Nor is it how high a bank scored above the minimum set by the Fed. The best measure is how much effort was required to pass. Wells Fargo had to cram the most — another fallout from all of its problems in the past year.

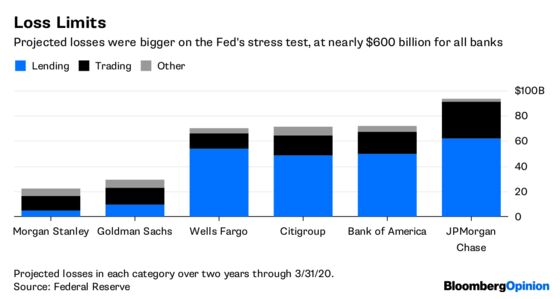

Risk in the banking system can be measured in any number of ways. One is to look at how much banks will lose on soured loans and bad trades during an economic downturn. This year the Fed estimated that in a severe economic downturn the largest U.S. banks would lose a collective $578 billion. That’s up from last year’s estimate of $493 billion, though it does appear that the test’s economic scenario was more dire this year. The biggest loser was JPMorgan Chase & Co., with losses of $93 billion, followed by Bank of America Corp. with $72 billion and Wells Fargo with $70 billion. Morgan Stanley, which is still a relatively small lender, would lose only $22.4 billion.

Another way to measure risk, and the one that has become standard since the financial crisis, is to look at how prepared the banks are for those losses. That’s what people are talking about when they say the banks are much safer than they used to be. One gauge is money the banks have already set aside to cover bad loans, called provisions. Based on that, the big banks, as I wrote recently, look pretty risky. Those reserves have shrunk close to the level they were before the financial crisis.

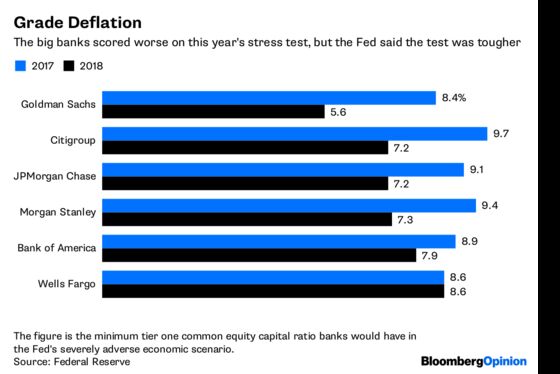

What most people look at, however, are the banks’ capital levels, which is the money they have to cover losses once those provisions have been drained. And it is on this measure that the banks look safe. Those capital ratios are much higher than they were a few years ago, though lower this year than last. (Again, that was likely because the Fed, after making the test easier for a few years in a row, tightened the screws a bit this year.) Nonetheless, the Fed predicted all of the banks’ tier one common equity capital ratios would stay above 4.5 percent, which is the minimum, even in a severe economic downturn.

Here’s where it gets interesting. You don’t want to be too close to that 4.5 percent, or 3 percent on the supplementary leverage ratio, which is another measure banks have to clear. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Morgan Stanley appeared to have cut it a bit close this year, which may affect their dividends and stock buybacks and how they do on next week’s test.

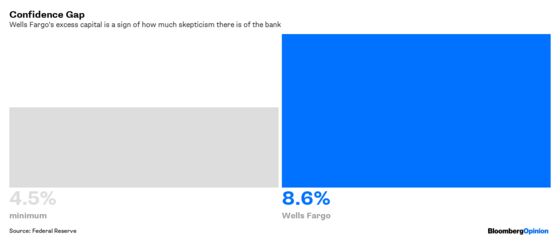

But you don’t want to be too far above that minimum, either. The more excess capital you have, the lower your returns will be. And the only reason you would hang on to extra capital is either because you have mismanaged the amount you need or because investors or regulators are requiring you to hold extra protection because they think you are too risky. That’s where Wells Fargo comes out the big loser this year. The Fed estimates Wells Fargo’s key capital ratio in an economic downturn would bottom out at 8.6 percent, nearly double the minimum and the highest of all the banks. Bank of America’s similar capital ratio would fall to 7.9 percent. Citigroup Inc., which had the highest minimum of the big banks last year, hit 7.2 percent this year. Goldman’s capital ratio would be 5.6 percent.

The point of the Fed’s annual stress test has been to prove to investors and depositors that the banks are safe. And mostly it has worked. JPMorgan can be projected to lose nearly $100 billion, and after this test no one will be worried that it’s too risky. But no one was really thinking that anyway. Nearly 10 years after the first test, what the stress test is truly doing is putting a number on the confidence gap in the banking system and for each bank. For Wells Fargo — after creating phony accounts, selling customers auto insurance they didn’t need and becoming the biggest funder of subprime lenders and gun makers — that number has become fairly large.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.