Don’t Follow Australia’s Grim Path on Migration

Whenever the supply of a highly desirable good is restricted, the black market will find a way of filling the gap.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Fariborz Karami had been held in Australia’s offshore detention system for five years when he killed himself in his mouldy tent on the Pacific island of Nauru Friday. Less than a month earlier, a 52-year-old member of Burma’s Rohingya ethnic group died after throwing himself from a vehicle near Australia’s other offshore detention center in Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island.

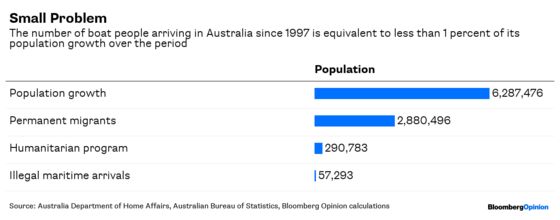

In all, 15 people have perished in the country’s offshore detention system since the camps in Manus and Nauru were re-opened in 2013, according to the Australian Border Deaths Database, a project of Melbourne’s Monash University, with seven of that total suspected suicides.

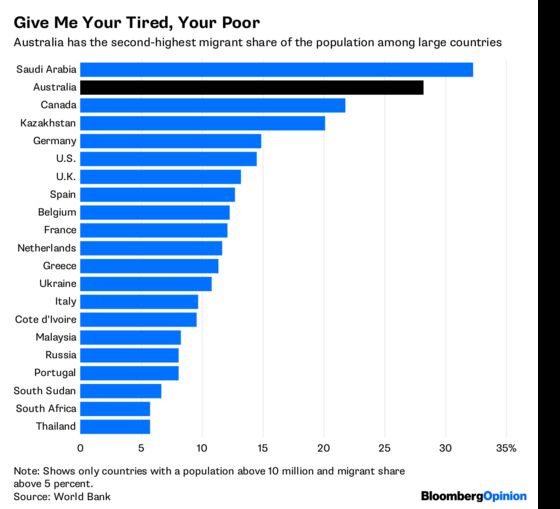

Australia’s treatment of people arriving by sea in search of asylum — “boat people,” as they’re known locally — has long been a stain on a nation that’s become a beacon for free movement since the end of its racist White Australia policy in 1973, with the proportionately highest migrant stock of any large country after Saudi Arabia.

The way that a system originally intended as a temporary measure has gradually turned into a “dire humanitarian situation” that’s contrary to “common decency” (in the words of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) offers a warning to the U.S. as it heads down its own path of more restrictive immigration enforcement.

The core justifications that have been offered for Australia’s detention of boat people since it started in 1992 are strikingly similar to those now being proffered in the U.S.: that the policy is essential both for the government to maintain control of its borders, and to prevent migrants from risking their lives on dangerous crossings.

All too rarely is it asked why refugees are prepared to make such perilous and expensive journeys in an era when mass air transport can move people around for far less than the $3,000-and-upward cost of being smuggled across a border. At its most basic, it’s often about supply and demand.

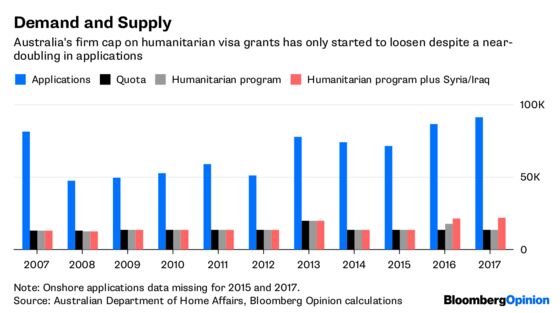

Australia, for instance, had until the past year held its annual migrant intake close to 13,750 since 1996. That’s despite a one-third increase in Australia’s population and a global group of at-risk people that’s risen from 20 million to 68 million over the period.

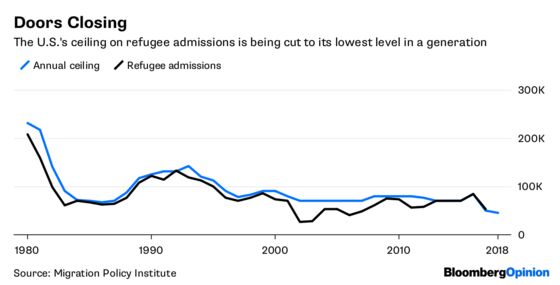

The U.S. is little different: Its ceiling on refugee admissions, which averaged about 113,000 in the 1980s and 1990s, had fallen to 75,000 since 2000 before being cut to 50,000 and, this year, 45,000 by the Trump administration.

The effect of this government restriction has been visible in the gap between applications for Australia’s various humanitarian migrant programs and acceptances: Only one in four people who’ve sought asylum and protection over the past decade have been accepted.

Some of those refuseniks have gone on to other countries such as those in North America, or the European Union. Some, to be sure, may have returned to their homeland due to a weakening of unrest or giving up on their hopes for a better life elsewhere. Many, though, have been left in the limbo that’s driven some to seek their chances paying people-smugglers to take them over the high seas separating Australia from Indonesia.

The lesson is the oldest one of prohibition: Whenever the supply of a highly desirable good is restricted — whether it’s liquor in the U.S. in the 1920s, or the right of asylum in Australia in the 2010s — the black market will find a way of filling the gap, and only the most draconian of policies will be able to stamp it out.

That’s why governments should acknowledge their own role in creating this problem. By imposing artificial caps on migrant flows that are driven by war and chaos, they create the demand for treacherous alternative paths across borders. By restricting numbers, they turn people from refugees worthy of sympathy in the public mind into illegal lawbreakers deserving punishment.

As the world has seen in Baghdad’s Abu Ghraib prison, the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment, and Australia’s own camps in Nauru and Manus, once you start treating the vulnerable as criminals who need to be punished in order to deter others, it’s remarkable the level of cruelty humans are prepared to accept.

The 1,995 children who were separated from their parents and detained in the U.S. between mid-April and the end of May aren’t many fewer than the 2,500 people of all ages who’ve been put into Australia’s Pacific detention centers since 2013.

America, with its noble history as a home for the world’s dispossessed, should be wary of following Australia’s path. A restrictionist approach to migration can look like a delicate tool for a temporary problem when it’s first taken up. Once in the hands of government, it’s a ratchet.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Katrina Nicholas at knicholas2@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.