Thanks to Fed, an Inverted Yield Curve Is Imminent

If Federal Reserve officials are truly trying to avoid an inverted yield curve, they have a funny way of showing it.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- If Federal Reserve officials are truly trying to avoid an inverted yield curve, they have a funny way of showing it.

Policy makers on Wednesday raised the central bank’s benchmark as expected while also shifting their “dot plot” higher for the next two years. They now anticipate a total of four quarter-point rate hikes in 2018, up from three previously. In 2019, the median estimate calls for a 3.125 percent fed funds rate (or a range of 3 percent to 3.25 percent). That means for the first time since the projections were introduced in 2012, the forecast for the following year is higher than officials’ estimate of the longer-term neutral rate at 2.875 percent.

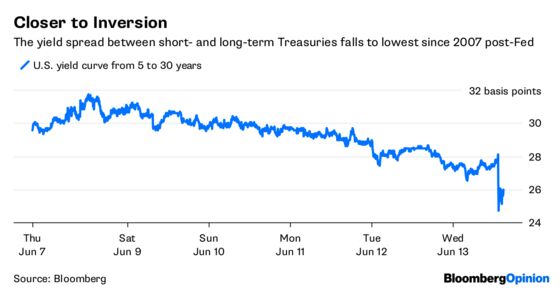

It should come as little surprise then that Treasury yield curves flattened to the lowest levels since 2007 after the Fed’s decision. The spread between two- and 10-year maturities fell to 39 basis points and the gap between five- and 30-year securities dropped below 25 basis points. That’s only logical, considering that central bankers see short-term rates as higher than the current yield on long bonds by the end of 2019.

Enough Fed officials have expressed concern about an inverted yield curve and what it signals for the economic outlook over the past few months that it’s surprising how willing they are to bring about that scenario. St. Louis Fed President James Bullard said last month that inversion was bearish for the U.S. economy and that “you could be talking about it in September. I don’t think it’s likely to happen that fast.”

Well, if the Fed follows through with another rate hike that month, a reasonable argument can be made that the yield curve will invert as soon as September.

“The yield curve is something people are talking about a lot, including FOMC participants,” Chairman Jerome Powell said during his press conference. “That discussion is really about what is appropriate policy and how do we think about policy as we approach the neutral rate?”

Now, an inverted yield curve has been a great tool to predict U.S. recessions, with the yield spread between three-month bills and 10-year notes falling below zero before each of the past seven slowdowns. But it doesn’t usually happen immediately. That means a recession could come in late 2019, in 2020, or even later. That probably doesn’t come as a surprise to most investors after one of the longest economic expansions in history.

But it does signal that this Fed, under Powell, is much different from its predecessors. It’s not going to go easy on monetary policy. It’s not going to be ultra-cautious. There will be a press conference after every meeting, starting in January. Treasuries knew what to do upon that realization, selling off across the curve, with 10-year yields topping 3 percent for the first time since May 24.

Stocks, on the other hand, weren’t so sure. The S&P 500 Index hit session lows, then rebounded, then hit new lows, then rebounded once more. But, in the grand scheme of things, they’re little changed.

It’s the yield curve, then, that sticks out. On the one hand, it confirms the bias among bond traders for flattening. But, as Bloomberg News’s Cameron Crise put it, it’s also a realization that “this isn’t your older sibling’s Fed anymore.”

Interest rates are headed higher, and it’s going to take more than a little turbulence— or fear of an inverted yield curve — to knock the Fed off course.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.