(Bloomberg Opinion) -- China’s plans to create a pipeline giant to aid development of its natural gas market are overdue, and welcome. Unfortunately, they don’t go far enough.

The state-owned champion, provisionally dubbed China Pipelines Corp., will combine the pipeline divisions of state-owned PetroChina Co., China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. or Sinopec, and Cnooc Ltd. A mooted market capitalization of as much as 500 billion yuan ($78 billion) would make it the world’s largest pipeline operator on that measure, comfortably outstripping Enterprise Product Partners LP at $64 billion.

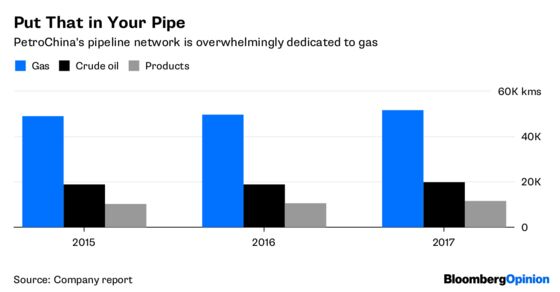

There’s much to like in that plan, given the way the current setup has helped stymie China’s drive to increase the role of gas in its domestic energy mix. At present, producers and sellers of petroleum control the midstream sector, with PetroChina owning a commanding majority of the pipes, and Sinopec and Cnooc carving up the remainder.

If China’s highways were owned and tolled by its three largest trucking companies, it wouldn’t be surprising if they favored their own freight over that of competitors, to the detriment of traffic as a whole. A similar thing appears to have happened with midstream petroleum infrastructure, which for years has been starved of much-needed investment.

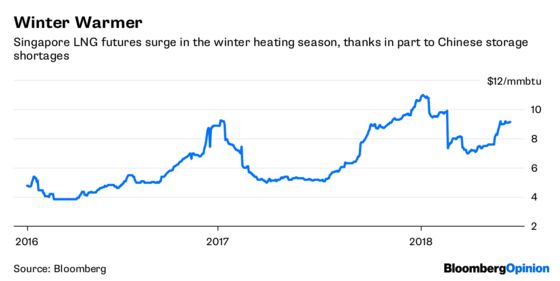

The network at the end of 2014 was capable of shifting about 240 billion cubic meters of gas, barely more than the minimum 220 billion cubic meters necessary to accommodate peak demand, according to a 2017 paper by analysts associated with Royal Dutch Shell Plc and China’s governing State Council. The same pipes would hardly carry more than half of the demand forecast for 2020 and only a third of 2030’s total, the authors wrote, while underground storage capacity is “severely lacking.”

The effect of that poor network design was glimpsed last winter, when a ban on coal-fired heating in northern cities and a shortage of storage capacity caused a supply crunch that helped drive Singapore LNG futures up about 25 percent in the three months through December.

A dedicated midstream operator would answer some of those issues. Assets from the big three could be transferred into the new company and external investors brought in to reduce their share to 50 percent, taking the network out of the hands of its biggest users and providing fresh capital to build infrastructure.

That’s probably the best way to address the issue in the short term, “given the urgency and importance of ensuring gas supply stability,” Miaoru Huang, a Beijing-based analyst for consultancy Wood Mackenzie, said by email.

Still, it leaves out an important part of the puzzle. After all, if China wants to keep up with the pace of demand, it needs to increase its pipeline network from about 72,000 kilometers at present to 150,000 kilometers in 2020 and 250,000 kilometers in 2030, as well as adding LNG terminals and additional storage capacity to take the edge off requirement peaks.

That’s less likely to happen under a state monopoly, whose incentives will be to sweat assets and maximise utilization of existing infrastructure before any expansion. A better option would be to carve up the network and create competitive tension between two or more players – essentially the policy that Beijing followed in the Deng-era restructuring of its oil and gas industry that created the big three oil firms.

One objection to such a structure is that pipelines are a natural monopoly. Almost all of the costs are the fixed ones involved in building them; as long as there’s spare capacity, the incremental expense of moving an extra cubic meter of gas down the line is infinitesimal. As a result, companies won’t build competing infrastructure because they know existing operators can undercut them, eroding returns.

That’s all true, but it’s worth reflecting on the amount of work being done by the phrase “as long as there’s spare capacity.” If demand is rising quickly and capacity is running out on the existing pipelines – precisely the situation China is facing – the competitive advantage shifts from the company with the incumbent infrastructure, to the one that can do the best job of building new lines.

By spurning that opportunity, China is ensuring a tighter gas supply market, and one more prone to regulatory capture by the big incumbent player – exactly the situation the current asset split is meant to be addressing.

These days, China’s policy seems more focused on creating powerful state-owned giants than establishing efficient markets, so a split of these assets probably won’t be on the cards any time soon. Still, that should be seen for what it is – a policy failure that will stunt Beijing’s ability to meet its growth and pollution targets.

China Pipelines Corp. may become a national champion, but the Chinese people will be worse off as a result.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Katrina Nicholas at knicholas2@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.