(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Brian Moynihan’s slow waltz to safety is clearing some of Bank of America’s dance floor. That might not be such a bad thing.

Bloomberg News reported last week that a number of top bankers have left Bank of America Corp. recently. The complaint of the departed seems to be that the bank is being too risk averse, costing it, and perhaps the bankers, deals. One of the most notable departures was A.J. Murphy, the head of global capital markets and one of the highest-ranking female bankers on Wall Street, who joined private-equity firm Silver Lake. Murphy hasn’t said why she left, but she was a top leveraged-finance banker, and that’s an area a bank would shun if it wanted to cut back on risk. And indeed, Bank of America has recently fallen to No. 2 in leveraged loans, behind JPMorgan Chase & Co., for the first time since 2009.

Moynihan has been pretty vocal about trying to win the title of the nation’s safest large bank. His letter to shareholders this year pledged to stick to “responsible growth.” A prominent board member, Frank Bramble Sr., kicked off the shareholder meeting by promising shareholders that the bank was not going to do “anything crazy.” Its bankers have been among those warning about problems in the commercial real estate market.

One reason Moynihan has been so vocal about his plans most likely stems from an effort to build some consensus from shareholders and employees for his direction for the bank. Clearly the employee departures are a setback. But a bigger reason is that you have to be outspoken if you want the strategy to pay off.

Soon after the financial crisis, several professors and policy experts, perhaps most prominently Stanford University professor Anat Admati, made the case that forcing the banks to be less risky might actually make them more valuable; at the very least they wouldn’t lose as much value as the bankers complained they would with more regulation. The idea was that even if banks had lower returns, investors would pay more for them because they were less risky. Moynihan is perhaps the first banker to truly test this theory, though Morgan Stanley, with its move toward asset management, has become safer. Goldman has also at times tried to convince investors it was paring back some risk, but its message has been inconsistent.

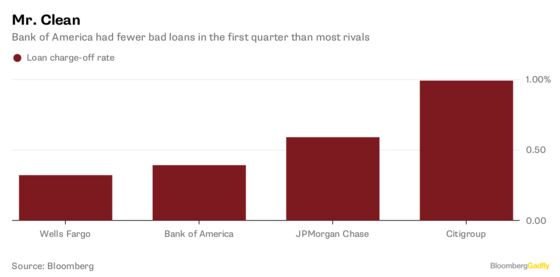

Taking on less risk has led to lower loan losses for Bank of America, as I pointed out after the last earnings announcement. But the real question about whether Moynihan’s plan is working has to do with that second part: Persuading investors to pay more for the bank’s returns. Figuring out if that is working is a little harder to do.

Bank of America’s shares have a price-to-book ratio of 1.26, which is higher than Goldman’s and Citigroup’s but still lower than the 1.31 average of its rivals. But Bank of America has a lower return on equity, which again is part of the lower risk model. The question is whether it is being compensated for its lower risk. And that does seem to be the case. Bank of America’s ratio of price-to-book to its return on equity, which in the most recent quarter was 10.9 percent, was 11.6, which is close to the highest of its rivals. The average is 10.2. And Bank of America’s price-to-book has been rising faster than its rivals as it has put its risk-off strategy in place. Its stock has also outperformed rivals over the past three years as well. That higher-than-average valuation, for its return, has essentially boosted Bank of America’s market cap by $39 billion, or nearly 15 percent, to $304 billion.

But it has lost business and bankers, as well. Was it worth it? The answer seems to be an easy yes. Revenue rose 9 percent in the past quarter, near the lowest of its rivals, which averaged a 14 percent increase. If Bank of America had increased its revenue at that level, it would have been $1.1 billion higher, and profits, based on its margins, would have been $330 million higher. Its return on equity would have also been higher, at about 11.3 percent. But Bank of America would have been riskier, so its price-to-book ratio would have been lower. The bottom line: The market value would be $28 billion less than it is now, using the average of its rivals.

Bank of America’s dealmakers may want Moynihan to pick up the pace, given the current tempo of the economy. But investors, at least for now, like his predictable two-step just fine. If he loses some bankers along the way, the beat will go on.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.