(Bloomberg Opinion) -- After Jay Clayton became chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission in early May 2017, agency officials promised more quality and less quantity. That was meant, in part, as a repudiation of Clayton’s predecessor, Mary Jo White, who brought the “Broken Windows” philosophy of law enforcement to market regulation.

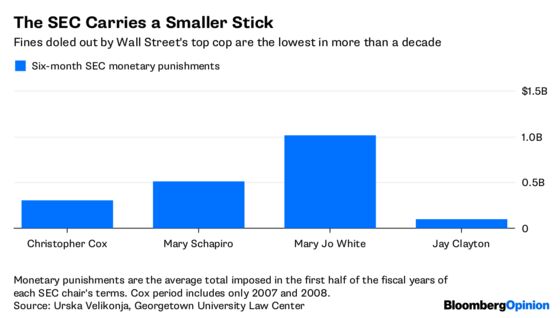

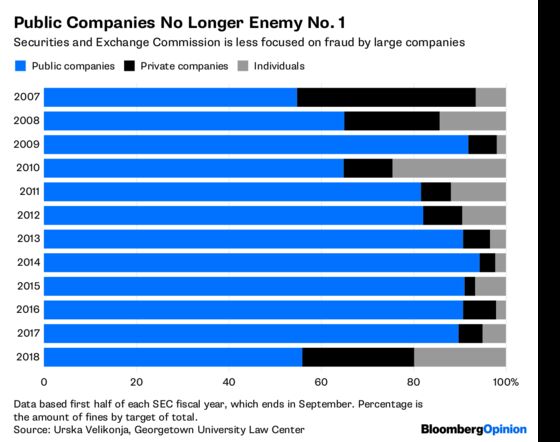

But 13 months in, Clayton’s SEC appears to be giving quality short shrift, at least as measured by the settlements it is reaching. According to a recent, previously unreported study conducted by Urska Velikonja, a professor of law at Georgetown University, the SEC’s monetary punishments plunged 93 percent in the period from October 2017 to March 2018 — the first half of the SEC’s 2018 fiscal year — compared with the amount in the period a year earlier. The total of $102 million was down from $1.4 billion and was the lowest of any similar period for at least the past 12 years. The number of cases in the same period was down by a quarter. That suggests Clayton has refocused the SEC’s lens on either smaller fish or smaller frauds.

“The cases they are bringing are ‘real fraud’ cases,” said Velikonja, referring to a shift away from administrative error cases, like failing to report a stock sale in a timely manner, and more toward those in which individuals were direct victims of fraud. “But are they really bringing cases that will make financial markets safer? I’m not sure.”

Another study of the October 2017 to March 2018 period, by the New York University Pollack Center for Law & Business and Cornerstone Research, which focused on SEC cases just against public companies, found that the average fine was $4.3 million. That was also the lowest six-month average in their database, which goes back to fiscal 2010. The largest penalty imposed during the first six months of the SEC’s fiscal 2018 was $14 million, far less than the $415 million Merrill Lynch paid the SEC for misappropriating customer’s cash in White’s full year running the agency.

In a potential sign of the SEC’s newer lighter touch, the agency in September settled its case against William Tirrell, the one executive who was under investigation as part of that Merrill case. His fine: $0. Tirrell’s sole punishment was to promise he “cease and desist” from breaking the law in the future.

The SEC publishes enforcement data once for its fiscal year, which ends in September, and its next report won’t come out until October, so a full picture of Clayton’s first year on the job is not easy to get. No study has yet to review his first 12 months as chairman, and most SEC cases take more than a year to develop. But a search of the Bloomberg Law database for the 13 months Clayton has been on the job produced 227 court cases in which the SEC is listed as the plaintiff. That was up slightly from 212 in the 13 months before Clayton, who was previous a top corporate lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell, started at the SEC. But the Bloomberg database does not include cases in the SEC’s own administrative court, which appear to have dropped in the past year.

The SEC did not return a call for comment.

Previous SEC chairmen have also faced criticism that they have been reluctant to bring cases against Wall Street and prominent bankers, particularly in the wake of the financial crisis. And Clayton has won some fans, even among the crowd that isn’t just looking for less regulation.

Sal Arnuk, a critic of high-frequency trading, said Clayton had “moved the ball forward” more than his predecessors. Separately, the SEC has proposed a pilot program that would limit payments that some say encourage brokers to send trades to the exchanges that pay the most rather than where clients will get the best prices. The exchanges have criticized the SEC’s proposal as misguided.

Cases against investment advisers are also up, though some say that trend started under White. “He’s better than feared on enforcement actions,” said Bartlett Naylor, a consumer advocate at Public Citizen. “We are not displeased, though the cases seem to be relatively small.” And Naylor said Clayton had appeared to defend shareholders’ ability to get resolutions on proxy ballets. Corporations have lobbied the SEC to limit the resolutions. Naylor said the SEC’s “Best Interest” rule for broker conduct — a potential replacement for the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule — was a missed opportunity because it relies too much on disclosure and doesn’t do a great job of defining what’s prohibited.

On other issues, Clayton has received more mixed reviews. The SEC, and Clayton in particular, have been vocal about potential fraud in bitcoin and cryptocurrencies in general. It created a fake initial coin offering to alert investors to the dangers, issued subpoenas and halted a few offerings. Nonetheless, critics say, the SEC has been slow to clarify what is and is not allowed among ICOs, even as the deals continue to suck in more and more investors.

More worrisome has been Clayton’s push to boost the number of initial public offerings — some of Wall Street’s most lucrative deals — which he has said is a key focus. He’s said he supports allowing less disclosure and for markets to lower the bar for companies to go public. Clayton has pushed Reg A offerings, which have so far mostly produced losses for investors. At the same time, Clayton has said he has been surprised by the level of fraud at smaller public companies.

But at least based on the evidence so far, it seems, it shouldn’t come as a surprise if Clayton’s SEC finds relatively little fraud elsewhere.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.