(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Imagine you are a director at a small-ish exploration and production company in the middle of an oil-market crash. Would you:

A) Approve spending $1.68 million to buy out the CEO’s and CFO’s minority stakes in a private jet, of which the company owns 80 percent already?

B) Do pretty much anything else?

If you answered (A) then, in another life, you might have served on the board of Comstock Resources Inc., which signed off on that deal in January 2015. A month later, dividends were "temporarily suspended" in order to "preserve liquidity."

Water under the bridge, of course – except Comstock recently announced a deal to sell an 84 percent stake in itself to a company controlled by Jerry Jones, owner of the Dallas Cowboys. That sounds about as thrilling as it gets in Texan oil circles, until you look at this chart:

The deal will help Comstock handle its mountain of debt – a net 8.5 times Ebitda at the end of 2017, according to data compiled by Bloomberg – and the stock has more than doubled since its announcement. On the other hand, that has only taken the stock back to where it was in early 2017. And the price is that Comstock’s non-insider shareholders get diluted down to less than 14 percent ownership. It’s tough to call that a home run.

Meanwhile, CEO Jay Allison’s total compensation doubled last year, according to Comstock’s recently filed proxy statement. In the decade ending 2017, he was paid almost $26 million in salary and bonuses, according to proxy filings – coinciding with Comstock generating a total return of negative 94.7 percent, according to Bloomberg figures. He was also awarded a notional $37.9 million in restricted stock and stock-units, according to annual proxy filings, although some of that was eviscerated along with the share price. If the deal with Jones goes through, $7.9 million worth restricted stock and units held by Allison will vest immediately.

Across the battered E&P sector, investors and analysts have lately kicked up a stink about poor performance and managers’ incentives. Even large, successful companies such as Pioneer Natural Resources Co. and Anadarko Petroleum Corp. have instituted reforms in response.

Comstock is much smaller (current market cap: $177 million.) I first got interested in it several months ago, when an anonymous Twitter account, @EnergyCredit1, posted a long, highly critical thread about the company’s management. So I took a look at the proxy statements. Comstock didn’t respond to several requests to discuss these issues.

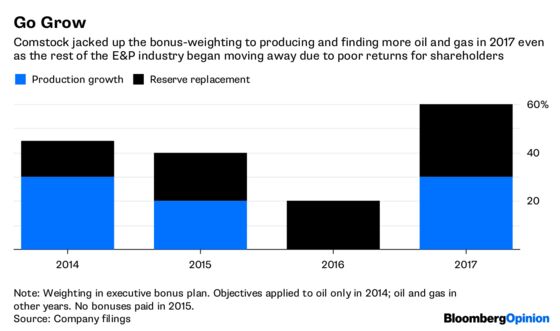

One noticeable thing is how Comstock’s bonus criteria move around. For example, in 2014, 30 percent of the target bonus was linked to growing the company’s oil production. That changed the following year to overall production growth (including natural gas), but now at 20 percent. In 2016, growth disappeared altogether from the equation, before coming back in 2017 with a 30-percent weighting. Here’s how those line up with Comstock’s actual production:

Short-term incentives do change; they’re short-term, after all. However, as Chris Crawford, president of compensation consultancy Longnecker & Associates, put it to me: “It’s not healthy to have big changes year to year, especially when it yields a result of high payouts and low performance.”

Focusing on absolute growth in production and reserves has damaged returns and balance sheets, not just at Comstock but across the sector – which is why so many are moving away from this. Goldman Sachs noted recently that 19 of 39 E&P firms it surveyed reported corporate returns or production growth per debt-adjusted share – which factors in capital discipline – as management incentives in their latest proxies, up from just four last year. Comstock, on the other hand, tied 60 percent of last year’s executive bonuses to boosting production and reserves.

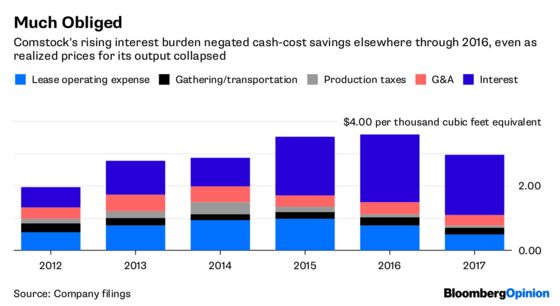

Meanwhile, controlling leverage, an objective in 2014’s bonus plan, disappeared after that. Which is unfortunate, because ballooning interest costs more than offset savings Comstock made elsewhere on a per-unit basis:

Even in 2014, managing leverage was merely one element in a bucket labeled “other key objectives”. A quarter of the bonus weighting in 2014, this bucket – including qualitative things like “leadership development” and “execution of strategic plan” – ballooned to 40 percent in the particularly hard years of 2015 and 2016.

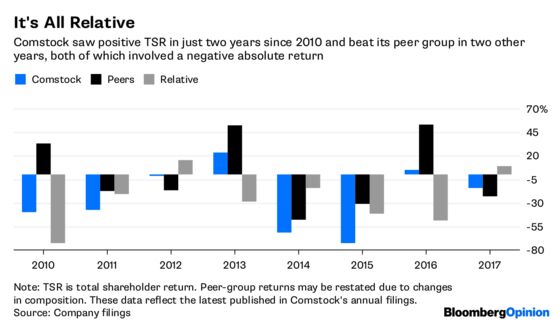

Another element, total shareholder return, or TSR, is objectively quantifiable. But, like many E&P companies, Comstock judges TSR relative to a peer group, rather than just in absolute terms. Besides a small role in bonus-setting, TSR largely determines the number of performance-based restricted stock units awarded as part of executives’ long-term incentive plan.

The key thing to note here is that 100 percent of the target number of those units is awarded, as long as Comstock’s TSR is at the 50th percentile for the peer-group – even if all are down in absolute terms. Comstock’s annual TSR has been positive in only two of the past eight years, according to its annual filings:

Comstock has actually improved on prior practices. Its proxy filings indicate that, until 2010, the CEO recommended his own salary and bonus. And in 2013, partly in response to criticism from Institutional Shareholder Services, Comstock enacted other reforms, including taking out the discretionary element of the bonus and requiring positive absolute TSR in order for future performance-based restricted stock-units to vest. Overall, Allison’s annual compensation in the five years after 2012 averaged $3.6 million versus $9.6 million in the prior five years. And in 2015, executives didn’t get their bonuses, given the suspension of dividends.

Then again, 2015 was also the year the board agreed to Comstock using precious cash to buy out the CEO’s and CFO’s interest in that plane. Meanwhile, the positive-TSR requirement related to those restricted stock units seems to have disappeared by the time the 2016 proxy was filed.

Doug Terreson, Evercore ISI’s veteran oil and gas analyst, published a detailed report on c-suite pay last summer in which he wrote “the most pressing corporate governance issue in energy today involves CEO compensation structure.” While higher oil prices have helped to perk up E&P stocks in recent months, fixing internal incentives is vital for long-term healing.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.