China’s Not Feeling the Yuan Market Love

The PBOC established the system to move the yuan, or renminbi, away from its historical soft peg against the dollar.

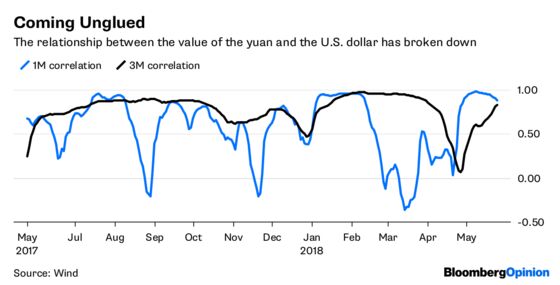

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The relationship between the value of the yuan and the U.S. dollar has broken down in the first few months of 2018, raising questions over the actions and objectives of China’s central bank.

Since unveiling a basket of reference currencies used to set the yuan’s exchange rate in 2015, the People’s Bank of China has largely left it alone. The PBOC established the system to move the yuan, or renminbi, away from its historical soft peg against the dollar, aiming to broaden the currency’s value-setting base and reduce volatility.

In practice, the system has resulted in the yuan closely tracking the value of a U.S. dollar index that measures the greenback’s movement against a broad basket of major currencies. The rolling three-month correlation between the yuan’s exchange rate and the dollar index has averaged almost 0.8 since the basket’s inception (a figure of 1 would indicate they move in perfect lockstep, while minus 1 would mean they move exactly in opposite directions).

Note that it’s an inverse-value relationship: When the U.S. dollar index rises, the yuan tends to fall, and vice-versa (since the renminbi exchange rate is commonly expressed in yuan per dollar, a higher figure indicates that the Chinese currency has depreciated).

For the three months from February through April, these correlations vanished. Whereas before a one-month coefficient would frequently hover upward of 0.9, the relationship was near zero and even negative. The dollar index rose about 6.4 percent between the end of January and May 29. Over the same period, the yuan lost only 2 percent.

What changed? At the start of the year, the PBOC told banks that traded foreign exchange to reduce use of a so-called counter-cyclical factor that was introduced in 2017 in an effort to lower volatility. This effectively weakened the importance of the yuan’s end-of-day closing price against the dollar, allowing banks to submit reference rates to the central bank that reflected more trading activity and smoothed out swings in the exchange rate.

However, if the counter-cyclical factor was the driving force, we should have seen a quick reaction after the announcement. In fact, correlations remained high into late January. So what is driving the change?

Beijing is facing immense pressure in two specific areas. One is trade. By propping up the renminbi’s value, China takes away one of President Donald Trump’s charges – that the country manipulates its currency to drive export growth.

The dollar’s rally should have pushed the yuan to below 6.5 or even 6.6 per greenback. Instead, it sits at 6.4. Given the trade pressures, it’s not unreasonable to ask whether Beijing is trying to appease Trump by manipulating the currency basket – a much less-noticed route than yielding to tariff demands.

The second factor is capital outflows. It’s possible Beijing is concerned that allowing the yuan to weaken too much will spur investors to pull money out of the country, and so is tapping the brakes. With current and capital account net outflows topping $500 billion after the unexpected yuan devaluation in August 2015, the government is hyper-sensitive to anything that might trigger a repeat.

Net outflows are currently close to zero, with banks and the foreign-exchange regulator applying greater scrutiny to every international transaction. Depreciation pressures have been reduced by the implementation in January 2017 of a rule that restricts banks to paying out only as much foreign currency as they receive.

Whatever the explanation, the problem that will remain is Beijing’s meddling hand in asset prices. The yuan basket was created not only to move away from a dollar seen as excessively volatile, but also to create the appearance of a market-determined exchange rate.

As in other areas of the economy, this remains a chimera. China controls the value of financial assets from the currency to stocks to commodities. In the equity and raw-materials markets, traders design strategies around what they expect the government to do.

If Chinese authorities are trying to support the yuan to weaken Trump administration allegations of currency manipulation, they can just as easily decide at some point to push it down. What Beijing fails to grasp is that manipulation is manipulation, whether the desired direction is up or down.

A market that’s loved only when it gives you the price you want isn’t a market.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.