(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Aluminum likes to cherish its image as the green metal.

Endlessly recyclable and – in North America and Europe at least – largely manufactured using renewable hydroelectric power rather than the dirty coal used to produce steel and cement, its reputation is so solid that Apple Inc., Alcoa Corp. and Rio Tinto Group are aiming to make it even greener.

A joint venture between Alcoa and Rio Tinto, with support from Apple and the Canadian government, will aim to make aluminum by 2024 with an innovative process that removes the carbon anodes that have been used in the smelting process ever since it was developed in the late 19th century.

That’s a worthwhile ambition. Aluminum is made in high-temperature electrolysis cells where powerful currents are passed through molten aluminum oxide – otherwise known as alumina, the same material that rubies and sapphires are made of. The process drives the oxygen from the alumina to a carbon anode with which it reacts to form carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide, while the leftover molten aluminum settles on the cathode.

That step deals a blow to aluminum’s low-carbon aspirations. Each metric ton of metal involves about 1.6 tons of carbon-equivalent emissions at the anode, with about two-thirds of the total from the direct consumption of the carbon and another third from relatively small but intense emissions of perfluorocarbons during momentary flaws in the smelting process.

The so-called inert anode technology being explored by Alcoa would replace the carbon electrode with alternative materials that would instead drive the oxygen off as a by-product. As well as cutting emissions, it would reduce the costs and operational challenges involved in replacing the rapidly consumed anodes.

There’s a beam in the eye of the industry, however, that makes anode technology look like a mote.

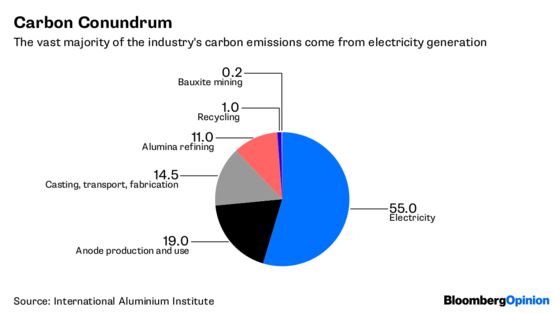

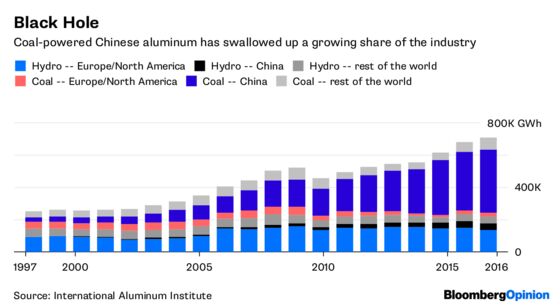

The vast majority of carbon emissions from aluminum come not from electrodes, but electricity. While it’s true that most smelters in the West are powered by hydroelectricity, the growth sector in recent decades has been coal.

Smelters consumed about 11,000 more gigawatt-hours of hydro power in 2016 compared to 2006, according to the International Aluminium Institute – but their draw from coal generators grew by 254,000 gigawatt-hours, with more than 100 percent of that increase coming from China where new fossil-fired plants offset closures elsewhere. (Natural gas, which is used largely to power a string of smelters in Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, contributed an additional 46,000 gigawatt-hours.)

About 55 percent of emissions globally come from power generation, compared to just 19 percent from anodes, according to the Institute – and those figures are based on the industry in 2008, so are likely to have deteriorated as coal dependency has risen.

We’re only making tentative steps toward addressing that issue. Beijing has begun cracking down on power plants that fall short of environmental standards and is attempting to rein in overcapacity in its metals industry. The world’s largest aluminum producer, China Hongqiao Holdings Ltd., last year closed 2.68 million metric tons of projects, compared to a total of 6.46 million tons in operation at the end of 2017.

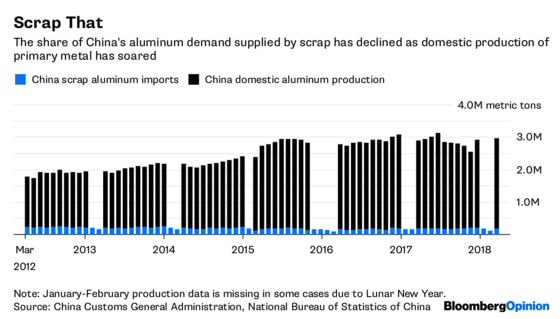

Still, coal generators co-located with mines and aluminum smelters and plugged into local power grids have been a driver of provincial electrification in China for many years and often have substantial cost advantages. Getting those smelters to switch to renewables will be challenging, given the higher expense of grid electricity and the location of many plants in northern and eastern parts of the country distant from the hydro resources of the southwest. Meanwhile, China’s tariffs on scrap imports risk eating away at the small but significant slice of aluminum output that’s recycled, by far the most climate-friendly way of making metal.

That’s no reason to dismiss the plan by Apple, Alcoa and Rio Tinto to reduce anode emissions – but you’ve got to put it in perspective. For every gram of Chinese-made aluminum in your consumer goods, about 15 times that amount of carbon has been put into the atmosphere. Until that’s fixed, this metal’s green credentials will look distinctly threadbare.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Katrina Nicholas at knicholas2@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.