Why It Took 233 Years to Get the First Black Female Supreme Court Nominee

Why It Took 233 Years to Get the First Black Female Supreme Court Nominee

(Bloomberg) -- Ketanji Brown Jackson has achieved something that few Black women in the legal profession have: Made it through the leaky pipeline.

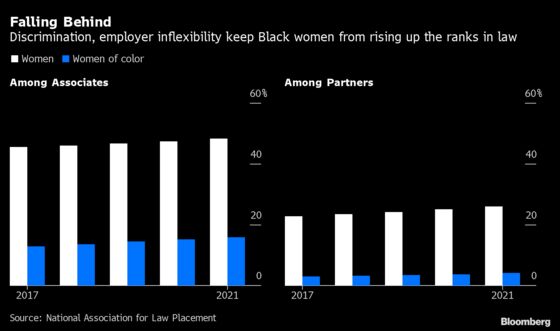

While Black women make up just under 5% of first-year law students, attrition rates among minority attorneys are as much as three times that of their White peers, according to the American Bar Association. Black women make up just over 3% of associates and less than 1% of partners. Jackson, who President Joe Biden last month nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court, is just one of 70 Black women to have served as a federal judge, and if confirmed, would be the first to sit on the nation’s highest court.

Professional women of all kinds lose ground as they climb the ranks for a variety of reasons including bias, lack of support for parents and insufficient opportunities for growth. Black women are even less likely than White ones to be promoted into management, and more likely to report being subjected to disrespectful comments, according to McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.Org surveys.

Within firms and court rooms specifically, Black women say they face bullying and, when they call out inappropriate behavior, retaliation. In industry focus groups, Black women said they faced stereotypes about being overly aggressive, and had to repeatedly prove themselves to clients with outsized results.

“I think it says a lot when women have broken through, when there have been legislative, judicial, social and other barriers to keep them down,” said Michele Bratcher Goodwin, a Chancellor’s Professor at the University of California Irvine. “Now, what does that mean for Black women? It has meant climbing, not hills, but in fact very steep mountains in order to dismantle historic patterns of discrimination, segregation and exclusion.”

In a 2017 speech at the University of Georgia School of Law, Jackson herself discussed the hurdles she faced as a mother and a Black woman in law.

“The hours are long, the workflow is unpredictable, you have little control over your time and your schedule — and you start to feel as though the demands of the billable hour are constantly in conflict with the needs of your children and your family responsibilities,” she said at the time.

Jackson, 51, said that it was the “inflexibility of the work schedules and assignments that became the deal breaker” for her working at a big law firm early in her career, leading her to a series of jobs in government and private practice, and ultimately to the bench. She was confirmed as a federal district court judge in 2013 and a federal appeals court judge in 2021.

Biases, however, can show up much earlier. In the 1980s, when Jackson told her high school guidance counselor she wanted to attend Harvard University, she was warned not set her “sights so high,” according to the White House. While she proved her naysayers wrong — later graduating magna cum laude from Harvard and cum laude from Harvard Law School — she was one of the few.

Due to segregation, Black people were “barely visible in law schools” until the 1960s, according to researchers; and it wasn’t until after the 1972 passage of Title IX of the Higher Education Act, which prohibited sex-based discrimination in enrollment, that law schools began to admit more women.

From the early 1970s to the mid-1990s, the percentage of African-American law students tripled, but the rate of progress slowed as anti-affirmative action initiatives took hold in some states. As of 2020, 8% of law students were African-American, according to the ABA.

Getting into and graduating law school is just the first hurdle.

In focus groups and surveys of 100 women of color who had graduated from law school 15 years ago or more, nearly all said they’d “experienced bias and stereotyping during the course of their legal careers,” according to a 2020 ABA report. Respondents said they had to walk a “tightrope” in order to avoid tropes like being seen as overly aggressive when dealing with discriminatory behavior. Earlier research found that more than half of women of color in the profession had been confused for custodial, administrative or courtroom staff.

Many also reported not being given many opportunities to work with high-profile clients, and had fewer opportunities for advancement. Black women and men made up less than 1% of the those within the top 10% compensation group at firms, a 2020 ABA survey found.

Some, like Andrienne McKay, a 26-year-old personal injury attorney in Georgia, say they question whether they’d be treated the same by colleagues if they were male, or White, in professional settings like depositions.

“Most of the time you refer to counsel by their last name, but there are times, opposing counsel will say ‘Andrienne’,” she said. “I have to stop at times and say, “We’re on the record right now, so Ms. McKay will be fine.’ You also don’t want to be seen as the ‘angry Black woman.’ So it’s always trying to balance, do I address this or let it slide?”

Under pressure to diversify their ranks, at least 118 law firms have pledged to enact the Mansfield Rule when hiring and making promotions, which requires that at least 30% of candidates come from an underrepresented group. Early adopters diversified their management committees at more than 30 times the rate of firms that didn’t use the rule between 2017 and 2019. Meanwhile, a record high of 28 Black women are leading law schools as deans or interim deans, and the 2021 class of summer associates at major U.S. firms was the most diverse ever. An increased focus on diversifying the cohort of judicial clerks may also open the way for more “firsts” on the bench, too.

During his presidential campaign, Biden pledged to diversify the courts — and he's tapped more women and minorities to the bench than either Trump or Obama. Of the 46 federal judges confirmed under Biden, 24% have been Black and 73% have been women, according to the American Constitution Society. These include a number of Black women, including Tiffany Cunningham, Eunice Lee and Holly Thomas.

A recent 108-page report from the Delaware Supreme Court Chief Justice Collins J. Seitz Jr. and Justice Tamika Montgomery-Reeves outlined additional strategies that firms and law schools could adopt to boost diversity.

They recommended creating paid internship opportunities at the pre-college level; a targeted media campaign to boost student awareness of career paths in the field; mentorship opportunities between judges and students interested in judgeship; and the creation of reporting requirements to measure the success of program initiatives.

The report also suggested adopting a scholars program as an alternative to the bar exam and a loan repayment program for those that go through the program.

“It takes intentionality,” said Yvette McGee Brown, who was the first Black female justice on the Ohio Supreme Court and is now a partner at Jones Day. “It takes saying to your partners, ‘I want you to mentor this person’ and you look for opportunities to have those diverse associates get experiences on important matters with important clients. And partners have to make sure that diverse lawyers have access to client-facing opportunities, because lawyers stay where they’re happy.”

By increasing representation, it shows those coming up the ranks what’s possible.

For Megan Byrne, a supervising attorney and director of the Racial Justice Project at the Center for Appellate Litigation, it’s encouraging to see a pathway for someone who worked in similar corners of the legal field as her; Jackson would also make history as the first public defender to serve on the Supreme Court.

“She has had family members who have been impacted by the criminal system,” said Byrne, who supervises representation of indigent criminal defendants. “It’s sad that this is a rarity and so groundbreaking, but it’s made me more hopeful for the future.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.