Wealthy Black Executives Take on Racial Inequality

Wealthy Black Executives Take on Racial Inequality

(Bloomberg Markets) -- More than a half-century after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was enacted and Shirley Chisholm became the first black woman elected to Congress, African American households still have half the income of white families. Sure, black unemployment is close to a record low, as President Donald Trump points out. But it’s still almost twice as high as the jobless rate for whites. The wealth gap is wide: Black families with bachelor’s degrees or higher have a net worth of about $68,000, about one-sixth that of white households with similar educations.

So for one group of black executives, the message was clear: The wealth we’ve accrued comes with the power—and responsibility—to enact change.

It started small, as these things do: free tickets for black teens to see the movies Selma or Hidden Figures; a personal donation to assist disadvantaged students pursuing engineering degrees. Then the 2016 election replaced Barack Obama with Trump, who spent years spreading the false claim that the first black president wasn’t a natural-born U.S. citizen.

Priorities changed in Washington. The group of executives raised their sights. In 2017 they created the Black Economic Alliance, which, by their reckoning, is the nation’s only political action committee founded by black business leaders and specifically dedicated to the economic issues—wealth, wages, work—that affect black Americans.

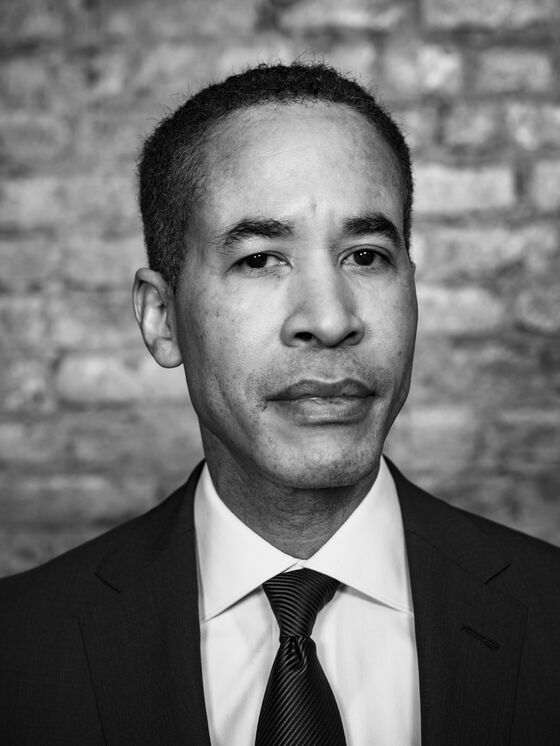

That focus on business and economic issues differentiates the BEA from other PACs led by or for African Americans. So does the business experience, and wealth, of its leaders. “We got to the point in our careers where we can take risks,” says co-Chair Charles Phillips, who earned $43.3 million in 2017 after a subsidiary of Koch Industries Inc. completed a more than $2 billion investment in his software company, Infor Inc.

Phillips, a former president at Oracle Corp., has said the BEA wants to learn from the political fundraising and influence tactics used by Charles and David Koch, majority owners of Koch Industries and among the most influential donors in conservative politics. (In January, Infor said it was getting an additional $1.5 billion, ahead of a potential initial public offering, from a Koch fund and from Golden Gate Capital.)

While the BEA is nonpartisan, all 26 candidates it endorsed in November’s elections were Democrats. They ranged from newcomer Lauren Underwood in Illinois, who became the youngest-ever black woman in Congress, to Tim Kaine, a white U.S. senator who won reelection from Virginia and was Hillary Clinton’s running mate in 2016. None of the Republican candidates the BEA contacted before the election responded to the group’s 10-question survey.

The BEA is tiny in the world of PACs. As of Dec. 7 it had raised $5.8 million, a fraction of the funds donated to groups such as the National Rifle Association’s Political Victory Fund or the National Association of Realtors’ PAC. And the BEA is still deciding where it stands on controversial economic policies that are dividing the Democratic Party, such as tax breaks for businesses.

Along with Phillips and his wife, Karen, co-founder of the Phillips Charitable Organization, the eight-person board includes co-Chair Tony Coles, a doctor who’s spent his career at drug and biotech companies, and Fred Terrell, a former vice chairman of the investment banking division at Credit Suisse Group AG. The 22-member advisory board features members of the Obama and Bill Clinton administrations, such as Clinton’s U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Robert Rubin and Obama’s National Security Adviser Susan Rice, as well as former Citigroup Inc. Chairman Richard Parsons and Michael Steele, the first African American to serve as chairman of the Republican National Committee.

The fledgling PAC is banking on this collective financial power and business acumen to give it a voice on economic issues that impinge on black Americans, leaving other important social justice causes to groups including the 110-year-old National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the NAACP. “We’re just trying to bring to bear what we know best—which is job growth and value creation for shareholders—in a way that will make an important difference in the lives of people,” Coles says.

Race is a defining factor for black Americans in a country that spent centuries systemically blocking them from the American dream. Even for those that reach the highest echelons of wealth and status, their fate remains precarious. African American boys from the richest U.S. households earn less when they grow up than white peers with similar pedigrees. Black men raised in the top one percent of incomes are as likely to go to prison as white men from households earning around $36,000, according to research from academics at the U.S. Census Bureau and Harvard and Stanford universities.

“We’re at that point in time when you have a critical mass of African Americans that have achieved a certain level of success in business, in health care, in technology, you name the industry,” says Carla Harris, vice chairman of Morgan Stanley’s Wealth Management division, who also sits on the BEA’s advisory board. “We do have a responsibility to lend whatever we have toward moving the needle and more importantly bringing others on board with us.”

But how best to do that? The BEA’s entrance into politics comes as economic solutions proposed by some Democratic progressives—such as newly elected New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s call for a 70 percent top marginal tax rate to finance a “Green New Deal”—conflict with those widely embraced by the business community. (The BEA focused its resources on helping candidates in the most competitive races. It didn’t take a position in the overwhelmingly Democratic district that Ocasio-Cortez won.)

The potential for tension between the private sector tilt of the BEA’s leadership and activists in the trenches in black communities surfaced during a post-election call with donors in December. One donor wanted to know the Washington-based group’s stance on tax breaks for investors in s “opportunity zones”—incentives designed to fuel development of economically disadvantaged areas.

Akunna Cook, the BEA’s executive director, paused for a few beats. She said she hadn’t closely studied the legislation, included in the 2017 tax overhaul, and would circle back after she looked into it.

The caller pushed further, starting to home in on what he called the “catch” in a tax plan that allows investors to reduce or defer taxes on capital gains.

Coles took a stab at a response, acknowledging that the issue fell right into the BEA’s wheelhouse. He noted that the zones had received bipartisan support from African American Senators Tim Scott of South Carolina, a Republican, and Cory Booker of New Jersey, a Democrat. Coles said the senators had told him they were looking for ways to “fill in the blanks” in the law. He believes that if entrepreneurial opportunities can be part of the zones, African Americans at least could benefit from that.

But the donor on the call said he was concerned that the rush of investment wouldn’t include African Americans, few of whom have large, taxable investment portfolios. And the investments could lead to neighborhood gentrification, pushing out low-income residents. Coles said there was still time before the plan was fully implemented—then suggested taking the discussion offline and moving on to the next question.

NAACP President Derrick Johnson, on the call, chimed in. Johnson, a Detroit native who previously had led the NAACP in Mississippi, said this wasn’t the first time in his life he’d seen a program like this. They may appear to provide “extremely lucrative entrepreneur opportunities,” but it’s important that residents reap the benefits and aren’t “preyed upon,” he said. Otherwise, we’ll “look at the project five years later and we’re displaced and we can no longer be part of the opportunity.”

Phillips, interviewed two weeks later, says he sees policies such as opportunity zones as a good start, albeit in need of modifications to encourage companies to move to the neighborhoods and employ black workers.

Similarly, Ocasio-Cortez and some other progressive politicians say that tax incentives to lure a corporate giant such as Amazon.com Inc. to New York and Virginia deplete public funds that could be put to better use helping the community. But Phillips sees potential in bringing tech jobs to new neighborhoods. “One of the reasons there is such a low percentage of people of color in technology is the largest companies haven’t been located in places where black people live,” he says. “In Seattle and the Bay Area, there’s just not a high concentration. But if you go to New York or outside of D.C., the labor pool changes dramatically.”

On the night of the November 2018 midterms, the BEA’s members gathered to watch the results at a five-story loft in Manhattan’s trendy SoHo neighborhood. The group had endorsed candidates in competitive congressional and gubernatorial races in places where the population was at least 10 percent black. Of the Democrats who were contacted, about 75 percent responded to the BEA’s survey.

Almost half of the BEA-endorsed candidates won seats in Congress or governors’ mansions that night. They included 32-year-old Underwood, a nurse with two master’s degrees who served in the Department of Health and Human Services under Obama, and Colin Allred, a 35-year-old civil rights attorney and former National Football League player who ran in an historically Republican district in Texas. They joined the freshman class of 2019, the most racially diverse ever in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Like the nation, the BEA is now setting its sights on the race for U.S. president in 2020. To better define its policy agenda, Cook says, the group plans to hire a research firm to learn more about what black voters and workers want in the economy. “Our goal is to make sure that every single candidate running for office has a defined policy position and a strong stance on what they’re going to do in office to help black communities economically,” says Cook, who was an adviser to Eric Holder, a former attorney general in the Obama administration, on the National Democratic Redistricting Committee.

Both political parties, Cook adds, need to do more to make sure they’re welcoming to black voters. Black voter turnout declined in the 2016 presidential election for the first time in 20 years after reaching a record high in 2012 when Obama was reelected. Democratic presidential aspirants understand the importance of black voters to their chances of winning the party’s nomination, as well as the general election in 2020.

Sharply focusing on that electorate could increase the BEA’s influence. “This is change from the ground up,” says Coles. “It’s working to get officials elected and then working with them for policy and legislative change. A hope and a prayer won’t be enough.”

Holman covers retail in New York.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stryker McGuire at smcguire12@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.