Virus Threat Grows in U.S. Where Millions Lost Health Coverage

Virus Threat Grows in U.S. Where Millions Lost Health Coverage

(Bloomberg) -- As a second coronavirus wave threatens America, millions are stranded without health insurance after losing their jobs when the disease first hit.

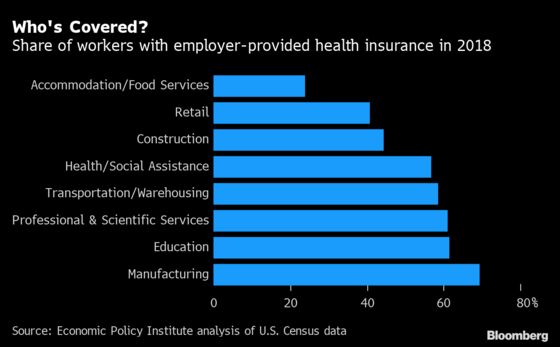

More than half the U.S. population relied on the workplace for health coverage, before a pandemic that’s triggered record job losses worldwide. In other developed economies, the newly unemployed could rely on systems of universal health care. In America, they’ve had to navigate a bewildering menu of options to figure out if they have access to a patched-together safety net.

While Congress has set aside billions of dollars to pay for virus-related care for the uninsured, they’ll be on their own for more ordinary medical expenses.

“With health insurance in particular, we have a social support system that really isn’t very functional when you have job loss,” said Ben Zipperer, an economist at the Economic Policy Institute in Washington. That’s a problem at the best of times, he said, “but it’s a real disaster when you have tens of millions of workers suddenly lose their job.”

The Covid-19 shock had likely pushed more than 16 million workers off employer-provided health insurance as of early May, the left-leaning EPI estimates. Unemployment data for June, due Thursday, will shed more light on the picture.

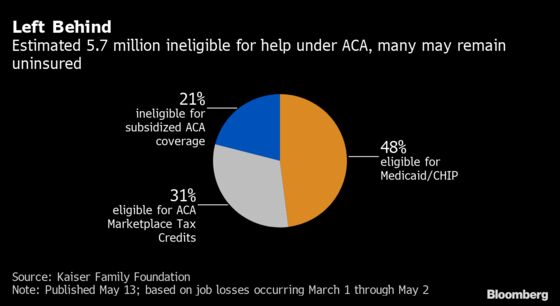

Including dependents like spouses and children, the Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that almost 27 million people could have lost their employer-sponsored coverage and become uninsured between March and May. It said that while most of those are eligible for some kind of subsidized coverage through Medicaid or the Affordable Care Act marketplaces, about 5.7 million probably aren’t.

‘Really Help People’

The ACA, known as Obamacare, aimed to broaden coverage in two main ways. For households with low or moderate incomes, it offered subsidized private plans that could replace job-based coverage. The 2010 law also expanded Medicaid, a program that offers free health insurance for the poorest Americans, to include those slightly above the poverty level.

But 14 states –- including Texas and Florida, where coronavirus cases have been soaring –- opted out of the latter provision. In those places, it’s been especially easy to fall through cracks in the system.

That’s what happened to Emily, whose asthma puts her in a high-risk group from Covid-19, after she was laid off from her sales job in Houston in March and lost health insurance. Her husband is also out of work, and she asked not to be identified by her surname discussing personal details while she’s seeking employment.

Emily had the option of keeping her workplace plan at her own expense under a program called Cobra, which allows Americans to extend employer-provided health coverage after a job loss. But she said that would have cost almost $2,000 a month for her and her husband.

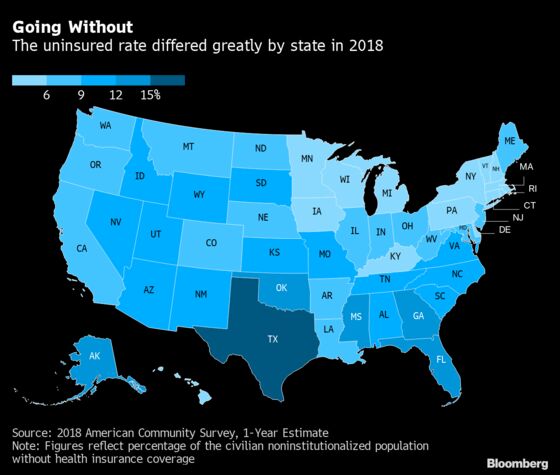

The couple didn’t qualify for Medicaid in Texas -- a state which had the highest share of uninsured people in the country as of 2018. Meanwhile, Emily’s application for unemployment insurance wasn’t approved till June. And that delay in turn meant that she fell short of the minimum income threshold for subsidies under the ACA, she said, which would have cut the cost of buying a plan on state exchanges to about $180 a month, from $450.

Her conclusion: “The system is not set up to really help people.”

‘One of Millions’

About 27.5 million Americans, or 8.5% of people, were uninsured in 2018. The numbers are down sharply by comparison with the pre-ACA years, and the reform probably helped prevent a bigger spike in the numbers during the pandemic, too.

How affordable its provisions are is a different question.

Brian Smith, 44, played double bass in the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra before he was furloughed in March when performances shut down. Smith initially kept his health insurance, because he was getting partial pay after his employer got a Paycheck Protection Program loan. But it ran out June 7, and the orchestra’s 76 musicians and librarians lost their coverage.

Going without insurance wasn’t an option for Smith, who needs physical therapy after breaking an elbow bone in May, and has a child with asthma. But “my costs are significantly higher” just when income has dried up, he said. “I’m one of millions of people that’s dealing with this.”

While U.S. unemployment has already begun to fall back from the highest levels since the Great Depression era, it may take longer to close the new gaps in health insurance.

Companies added 3.1 million workers back onto payrolls in May, likely helping many to regain employer-provided health insurance. But much of the re-hiring was in industries like hospitality and retail that are relatively less likely to offer such benefits -- a trend that’s expected to continue in the June data coming this week.

Roll the Dice

Meanwhile, some 6 million white-collar jobs, from professional services to real estate, are vulnerable to a second wave of layoffs. State and local governments continued to cut staff in May, and may be forced into further reductions as revenues decline. About two-thirds of public-sector workers were covered by health insurance through their employer in 2018, according to EPI.

“It’s probably a safe bet to think that this is still going to be a disaster that’s unfolding,” Zipperer said.

A recent survey by the Commonwealth Fund found that among adults who had insurance through their workplace, and saw their job disrupted by the pandemic, one in five said they or their partner are now uninsured.

Zachary Seif in Evansville, Indiana, has been without coverage for about two months, since he was permanently laid off from his job selling furniture a month after being furloughed.

Due to a mistake on the unemployment insurance application by his former employer, Seif says, he still hasn’t received any of the money. Even so, he says he doesn’t qualify for Indiana’s Medicaid program. “It is super unfortunate to be at that cutoff,” he said. It’s “an arbitrary number because everybody’s expenses and costs are different.”

Seif has leaned on his still-employed fiancée, and a philanthropist he reached out to on Twitter, to pay for two months of his medications. He has a new job lined up at a car dealership starting in July -- which would mean that two months later, he’ll once again be getting health insurance via his employer.

Until then, he’s planning to roll the dice, and go without.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.