Virus-Test Stampede Bypasses 10,000 U.S. Urgent-Care Facilities

Virus-Test Stampede Bypasses 10,000 U.S. Urgent-Care Facilities

(Bloomberg) -- America’s Covid-19 testing push has relied on pharmacies, hospitals, state health departments and even grocery chains to accommodate the exploding demand.

One logical option hasn’t been tapped: the 10,000 urgent-care facilities spread across the country. They say that while they’ve stayed open for business and ready to test even as patient visits plunged during the lockdowns, they’ve largely been left out of the equation.

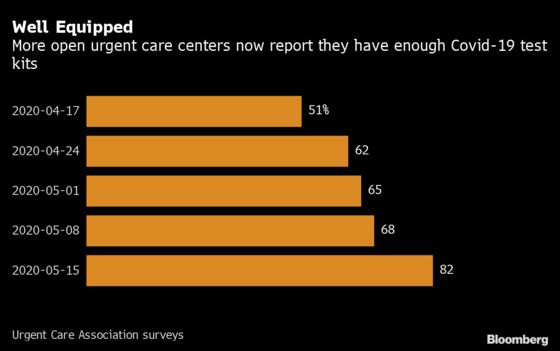

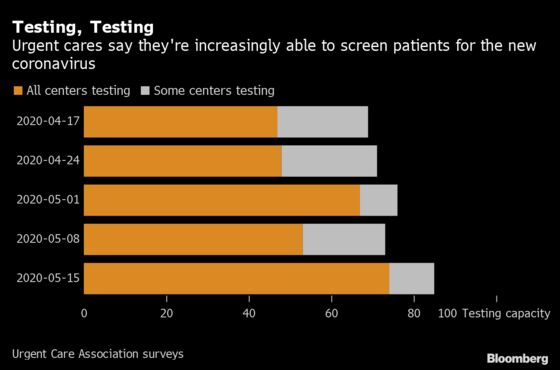

In the early stages of the pandemic, urgent-care clinics had little testing bandwidth. But after moving to close the shortfall, facilities now find the tests are piling up unused despite continuing U.S. efforts to expand Covid-19 screening and reopen the economy. Laurel Stoimenoff, chief executive officer of the lobbying group the Urgent Care Association, calls it “baffling.” John Radford, a physician who founded New York chain WellNow Urgent Care, says urgent-care facilities are a “blind spot.”

While it’s hard to say exactly how much testing capacity is going unused, the Urgent Care Association says the industry has the ability to do about 500,000 tests a day. Right now, they have the ability to treat 390,000 more patients a day than they’re currently seeing, based on data from Experity Health, which provides back-office services to nearly half of U.S. urgent-care centers. That translates to 11.7 million more people a month. Covid tests take less time than a traditional visit, so these numbers may underestimate how many more people urgent cares are capable of accommodating.

“I haven’t heard one public health official say, ‘Just go to your urgent care and get tested,’” said Experity CEO David Stern. “Almost everyone has an urgent care within a 30 minute drive to get that testing and treatment.”

‘Completely Siloed’

Urgent cares’ exclusion illustrates the difficulty of organizing a fragmented health-care system to respond to a nationwide pandemic. Harnessing their diagnostic capacities may be more crucial than ever as Trump administration officials push to more than double the country’s testing, and experts call for even greater testing capacity to find Covid-19 patients and prevent outbreaks as workplaces, schools and restaurants reopen.

“We are completely siloed and there’s no nationalized approach to testing,” said Susan Butler-Wu, an associate professor of clinical pathology at USC’s Keck School of Medicine.

Bloomberg spoke with half a dozen urgent-care companies with hundreds of locations spanning the Midwest, Northeast, South and mid-Atlantic states. They said they have abundant testing capacity but weren’t being fully utilized.

Additional diagnostic firepower is sorely needed as experts say mass testing -- to the tune of at least 900,000 tests daily -- will be key to stemming further outbreaks, especially as states reopen. The U.S. averaged roughly 330,000 tests a day last week, a little more than double the testing rate in mid-April, according to data from the Covid Tracking Project, a volunteer initiative to monitor virus data.

In the face of test-kit and protective-equipment shortages, urgent cares got a relatively late start in setting up robust testing capabilities. Now, though, they say the problem is not enough patients are coming through their doors. In early March, centers averaged 231 visits a week, according to Experity. That plunged to a low of 88 the week of April 11. Patients are starting to return, and the week of May 30 saw the average rise to 145, the survey found.

That may reflect a messaging gap. The Urgent Care Association says that local and national officials largely aren’t directing patients to get tested at their facilities. And 30% of urgent cares the trade group surveyed said they don’t think their local community is aware of their ability to conduct testing. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention referred questions on the role of urgent care in testing to the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which said in an emailed statement that it was focused on “the principle of locally executed, state managed, and federally supported response.”

In Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles, two cities where health officials have promoted getting tested at urgent care sites, the centers saw a marked increase, according to data gathered by Experity.

Lobbying Voice

As a relatively young and fractured industry lacking the consolidated heft of large retail pharmacies and the associated lobbying firepower, urgent cares may well have been politically disadvantaged from the start.

Compared with companies like CVS Health Corp., Walmart Inc. and Target Corp. that the Trump administration turned to to lead the country’s testing push, the urgent care lobby’s presence in Washington, D.C., is meager. In the first quarter of this year, it spent just $5,000 on federal lobbying, “a David to a Goliath-like CVS Health,” which spent $3.5 million on lobbying during that period, said Sheila Krumholz, executive director of the Center for Responsive Politics.

Bigger industry players are “able to hit the ground running when an opportunity or crisis arises. They have the people in place, and those people have relationships and expertise,” Krumholz said. “Unfortunately, those who may be best equipped may not be able to or may not have invested in those lobbying relationships, so they may not have the loudest voice.”

The Urgent Care Association’s Stoimenoff has taken her pleas to decision-makers, including the CDC. When the department of health in her home state of Arizona launched a testing blitz that didn’t include urgent cares, she called to successfully lobby for the facilities’ inclusion.

An Arizona Department of Health Services spokeswoman said the agency initially reached out to a distribution list of providers to conduct its testing blitz but has since expanded its outreach. As of May 16th, there were more than 80 providers participating and the department “greatly appreciates” its collaboration with urgent cares, among other providers.

Roadside Ads

When traffic dropped 85% at some Velocity Urgent Care-branded centers in Virginia, Chief Executive Officer Alan Ayers turned to TV ads for the first time and even roadside signs that he’d associated with junk haulers or house painters.

“There are populations we needed to reach and we were concerned we couldn’t reach them other ways,” Ayers said. It worked and he said colleagues around the country have reached out to him to replicate his approach.

The Urgent Care Association’s Stoimenoff says the industry was practically built to do this testing. For example, centers often have back doors to take emergency patients out, a feature that lets suspected Covid-19 patients bypass other patients in waiting rooms, she said.

Northeast Georgia Physicians Group, a practice with more than 65 locations in northern Georgia, agrees, having early on leveraged four of its urgent cares to do much of its testing.

The walk-in facilities were “already a logical source of care” since they’re in central locations and open nights and weekends, said Monica Newton, a family physician who leads the group’s quality and patient safety council. And with ambulance bays at the ready for more serious cases, they’re well-designed for this type of work, she said.

Dave Reid, a 36-year-old web developer who lives in Omaha, Nebraska, first tried to get tested in late April. He was told he’d need to be hospitalized to get one.

Still sick, one morning in early May he went back to the same testing center, a local urgent care run by the University of Nebraska. Within an hour of arriving, he was swabbed for the test while sitting in his car.

“I was just surprised that they were doing it that easily,” Reid said. “Because they’ve been talking about doing some drive-through testing in Nebraska, setting that up, I kind of assumed I would have to wait for that to be completed.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.