VA Hospitals Are the U.S. Safety Net. Covid-19 Exposed the Holes

VA Hospitals Are the U.S. Safety Net. Covid-19 Exposed the Holes

(Bloomberg) --

The Department of Veterans Affairs is supposed to provide a safety net for the U.S. medical system in times of crisis.

Yet its hospitals have treated just 135 civilians afflicted with Covid-19, according to numbers released this week, even as coronavirus infections have pushed tens of thousands of Americans into the nation’s hospitals.

The limited response stems in part from efforts to rein in the VA’s medical services, after a series of political battles over whether to privatize elements of the nation’s largest hospital network. In the early months of his term, President Donald Trump assigned an unconventional group to oversee the VA -- his son-in-law, senior adviser Jared Kushner, and three political advisers who socialized at his Mar-a-Lago resort. Their involvement caused so much bureaucratic distress that the VA ended up with an assortment of vacancies in high-level management positions.

The Trump administration has been increasing funding for veterans to seek care from private doctors, while presiding over chronic staffing shortages within the VA’s hospital system, the Veterans Health Administration. In the months since the coronavirus began threatening the U.S., the White House task force and agencies responding to the crisis have kept the VA largely on the sidelines.

That late and limited involvement is particularly surprising because the VA was among the first federal agencies brought in to monitor the virus. In early January, as the deadly new illness emerged in China, a VA doctor was embedded in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to study its spread. By the end of January, a VA medical expert warned senior officials that the virus could devastate the U.S. medical system and economy and that VA hospitals needed more safety equipment.

Since then, VA employees have grappled with a shortage of protective gear, including for nonmedical workers who’ve been tapped to screen new patients, several of them said in interviews. Top VA political appointees nonetheless turned down offers of funding from Congress in early March to buy protective gear for medical staff of its 170 hospitals and 1,074 clinics. It wasn’t until March 23, after a national emergency had been declared, that the agency released its Covid-19 response plan. It has treated more than 5,000 Covid-19 cases overall, almost exclusively among veterans.

With staff at VA hospitals struggling to anticipate the needs of veterans, the agency has taken only modest steps to fill its congressionally mandated “fourth mission” -- providing a safety net for the civilian hospital system.

The VA provided 50 acute- and intensive-care beds in New York City, for example, as authorities there prepared to accommodate thousands of patients in parks and convention halls. Currently 37% of the VA’s acute care and ICU beds are in use nationwide, according to a recent report to Congress reviewed by Bloomberg.

“How can you expect them to carry out their fourth mission when you’re busy taking away resources to carry out their first mission?” asked Suzanne Gordon, a senior policy fellow at the Veterans Healthcare Policy Institute, who has written extensively about the VA’s evolution.

In a written statement, the agency said it has appropriate protective gear for its workers. It said that while its response plan was made public in late March, planning began in early January before the first confirmed U.S. case. As for pitching in to help civilians under a national emergency, it said it responds to requests from states that are routed through the Federal Emergency Management Agency. The “VA will only accept such assignments when they do not negatively impact veteran care, as taking care of veterans is always VA’s first priority,” according to the statement.

The VA this week broadened its policies on personal protective equipment to provide masks more frequently to some workers. It also underscored its commitment to civilians, with a statement outlining how it freed up a few hundred beds in hard hit areas including Louisiana and Illinois, lent several medical staffers to hot spots in Connecticut and Massachusetts, and dispatched a mobile pharmacy to Detroit.

“VA is in this fight not only for the millions of veterans we serve each day; we’re in the fight for the people of the United States,” VA Secretary Robert Wilkie said in the statement.

‘At the Forefront’

On paper, the VA should be poised to pitch in during a public health crisis. It has 8,862 acute care and 2,951 ICU beds and close to 3,000 ventilators. In recent years, public health studies have shown that VA hospitals often produce better treatment outcomes than their civilian counterparts. The agency is well positioned to be “at the forefront of the nation’s response to the crisis,” former VA head David Shulkin said this month.

Founded in 1930 and elevated to a cabinet-level agency in 1989, the VA has become one of the government’s biggest agencies and a focus of budget battles. Years of efforts to privatize many of its functions have resulted in upheaval. The Trump Administration expanded funding to steer veterans into private care, raising administrative costs without achieving the desired goal of shorter wait times for patients. The White House has said it has no intention of privatizing the current system, but Shulkin has written that he was ousted in 2018 by presidential tweet because he was viewed as an “obstacle to privatization.”

At the time the coronavirus crisis hit, the VA had a staff of about 400,000 -- and roughly 50,000 vacancies that include doctors and nurses, according to a June 2019 agency report. That means its bed count likely includes many it can’t actually employ, said Marilyn Park, a legislative representative for the American Federation of Government Employees, or AFGE.

The staffing gaps extend to the top of the agency. The Undersecretary for Health position has been vacant for much of Trump’s administration. The VA’s Office of Emergency Management was left leaderless for months after its chief stepped down in 2018. VA officials testified to Congress that the vacancy, now filled, hobbled their ability to learn from missteps after 2017’s Hurricane Maria left a VA facility as Puerto Rico’s only functioning hospital.

The VA has reported that the agency has lower turnover than other cabinet agencies and the health-care industry.

Mixed Messages

As the coronavirus pandemic spread, the agency sent mixed messages about its readiness and commitment to civilian hospitals. On March 4, an agency official assured Congress it had enough money, staffing and protective equipment. “We are the nation’s surge force,” Secretary Wilkie told National Public Radio two weeks later.

Wilkie later tempered those expectations, telling Congress and hospital officials that the VA needed approval from FEMA and the Department of Health and Human Services to treat civilians. The congressional relief bill passed in late March, the CARES Act, included $17 billion in additional funding for the VA to provide Covid-19 care.

As of Monday, the VA was treating 83 nonveteran patients, even as more than 60% of its acute care and ICU beds were sitting empty, according to a VA report to Congress. Like many hospitals across the country, it has cleared space to ramp up where needed. The VA referred questions about its use of funding for civilian care to HHS, which didn’t respond to requests for comment.

As it scrambles to care for veterans, the VA is battling absenteeism. According to the Covid-19 readiness plan the VA published in late March, 40% of staffers could fail to report for duty in a severe outbreak due to illness, family-care duties or fear of contracting the virus.

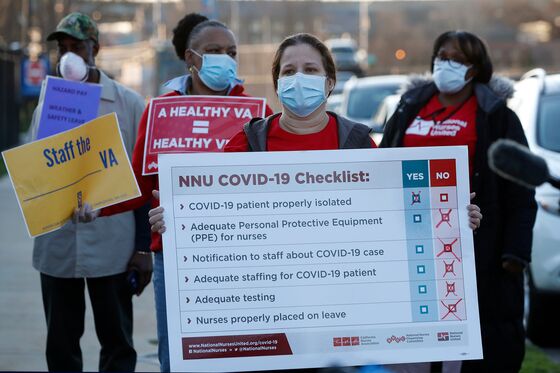

Those fears are widespread. According to workers and union representatives, protective equipment has been in short supply at sites in California, Illinois, Missouri and Arkansas. The VA in Houston sent an email soliciting masks from the public. In Northern California, management sent employees a link to a video about how to make masks, and some staff members have started making their own protective gear out of T-shirts and bras, according to employees there.

Some of these people said that while doctors and nurses had access to masks, administrative employees didn’t. In several locations, employees said, these unprotected workers were assigned to interview walk-in patients and in some cases take temperatures to screen for suspected Covid-19 cases. One worker in Illinois recounted how a colleague tearfully grappled with two bad options -- getting written up for refusing to do work with potential virus exposure, or risking getting himself and his family sick.

The VA, which began virus screenings on March 11, said Monday that 1,530 of its workers have tested positive for Covid-19. Ten have died.

“Employees know ‘this is my job,’ but they’re terrified because they can’t get the stuff they need,” said Daniel Scott, the president of an AFGE local representing VA employees in Arkansas, Oklahoma and Missouri. “It’s like going into a combat zone and you’re about to be attacked and they give you a hammer because you’re out of machine guns,” he said.

Following a complaint filed by AFGE, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration is opening an investigation “concerning worker exposure to patients with Covid-19,” according to a letter sent to the union by the agency.

Asked about the probe, an agency spokeswoman said the VA follows CDC guidance on personal protective equipment and that there is “no truth” to allegations that employees aren’t adequately protected. The VA’s employee infection is less than 1%, she added, citing other facilities with higher rates.

‘Amazingly Well’

Similar concerns arose in a review conducted in late March by the VA’s inspector general’s office. Agency managers were also worried about staff shortages and that their treatment strategy left gaps in its coordination with civilian health-care networks, the IG said.

Responding to the audit, VA officials said its emergency planning was sound. They criticized the inspector general for its unannounced visits to hospitals, which they said could have spread the virus. In a written statement, the VA added that its employees were performing “amazingly well” in a rapidly changing environment.

During the IG review last month, officials at most VA facilities said that if they are overwhelmed with veterans suffering from Covid-19, their fallback plan is the inverse of the fourth mission: they would send patients to the private, community and university hospitals they’re supposed to support, the inspector general found.

It’s “disturbing and infuriating” that the VA has provided little aid to civilians and endangered its staff, many of whom are veterans who took an oath to support the public, said Kristofer Goldsmith, assistant policy director at Vietnam Veterans of America.

“When you have a government being run by people who don’t believe government works, you get a government that doesn’t work,” he said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.