UnitedHealth’s Recipe for Lower Costs: Send Patients to Its Own Doctors

UnitedHealth’s Recipe for Lower Costs: Send Patients to Its Own Doctors

(Bloomberg) -- UnitedHealth Group Inc., the country’s largest health insurer, is selling a new plan that directs patients to see the company’s own doctors, a wager that some people will give up access to a greater range of physicians in exchange for lower premiums.

The company’s Optum division, the source of half its profits, has spent years buying medical practices and now employs, manages or contracts with almost 50,000 doctors, according to a recent securities filing. That’s equivalent to roughly 5% of the practicing physician workforce in the U.S.

The new coverage plan, called Harmony, relies on Optum doctors and a small number of outside providers. A tighter, more coordinated network can save customers money and improve patients’ care, UnitedHealth says. Harmony’s premiums are about 20% lower than its own comparable HMO plans.

A number of insurers are promoting similar plans in the face of complaints that insurance often costs too much and covers too little. Blue Cross Blue Shield plans and CVS Health Corp.’s Aetna are marketing lower-cost coverage options that steer members to a smaller selection of doctors and hospitals they say are top-performers.

“You’re redirecting employees to providers who are demonstrating higher value care and improved outcomes,” said Jennifer Atkins, vice president of network solutions at the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association.

UnitedHealth said 35,000 people have signed up for Harmony in Southern California, the first market where it's available, since the company began selling it to employers there in the second half of 2019. The company is paying agents sales bonuses of $100 for each member who enrolls, compared to $50 or $25 for most other plans, according to a document distributed to brokers. Executives have said they will expand it to Seattle and Texas next.

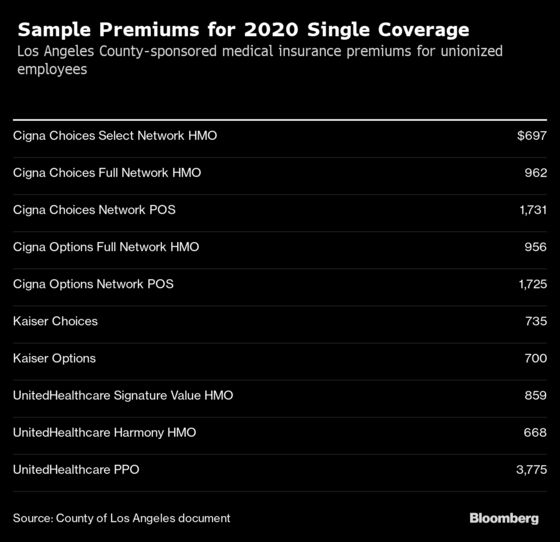

Premiums for Harmony are lower than competing plans from Kaiser Permanente, the large California-based HMO, and Cigna Corp., according to rates for Los Angeles County-employee medical plans posted to the county’s website.

Insurance plans that let members go to any physician they choose, known as preferred-provider organizations, or PPOs, cost more than plans that control which doctors people can see. That’s because providers will often accept lower rates in smaller networks that steer more patients to their practices.

Health-maintenance organizations, or HMOs, fell out of favor in the 1990s after a backlash against insurance-company restrictions. But with health-care costs squeezing the budgets of more families and employers, the idea is getting renewed attention.

“Narrow networks make really good sense,” said Jeff Levin-Scherz, co-leader of the health management practice at consultancy Willis Towers Watson. Because health-care prices vary widely, and high-priced care isn’t necessarily better, “you can often buy much higher quality at the same cost, or maybe even, in some instances, at lower cost,” he said.

Less than 20% of large employers currently offer plans with “high-performance networks,” an industry term for plans like Harmony, according to a Willis survey last year. Another 35% said they were considering the strategy for 2021. Employers typically offer these plans as an option alongside broader networks.

Drawing lessons from earlier backlash to HMOs, insurers position their new offerings as curated networks that steer patients to a list of top clinics and hospitals.

The Blue Cross Blue Shield Association is marketing a national high-performance network with what it touts as “carefully selected” clinics and hospitals that will be available in 2021. Walmart Inc. started steering some employees to “featured providers” in certain markets this year. In Atlanta, CVS Health’s Aetna insurance unit announced a “Whole Health” plan with limited networks that will include the company’s new health hub primary care centers.

Alone among its competitors, UnitedHealth has made owning medical practices a core part of its strategy, allowing it to turn expenses for its insurance business into revenue for its Optum health-services arm. Harmony is one of the clearest examples of the company stitching the businesses together. The plan “unites care and coverage,” Optum Chief Executive Andrew Witty said at an investor conference in December.

Wary Regulators

Federal and state regulators have expressed some wariness about UnitedHealth consolidating doctors and health plans under the same corporate umbrella. After the company reached a $4.3 billion deal to acquire practices employing thousands of physicians from DaVita Inc. in 2019, the Federal Trade Commission required UnitedHealth to divest DaVita’s physicians in Las Vegas to gain approval for the transaction. Otherwise, UnitedHealth would have “a near monopoly” on managed-care provider services sold to Medicare Advantage plans in the region, the agency said.

(Peter Grauer, the chairman of Bloomberg LP, the parent company of Bloomberg News, is a member of DaVita's board.)

Colorado’s attorney general also required UnitedHealth to lift its exclusive contract with one of the state’s major hospital systems before acquiring the DaVita doctors, and required the medical practices it purchased to continue contracting with UnitedHealth competitor Humana.

In New Jersey, a group of independent doctors have accused UnitedHealth of cutting them out of the company’s Medicaid plan there, sometimes directing patients to Optum physicians instead. UnitedHealth said the changes affected less than 2% of physicians in its New Jersey Medicaid network, and members still had access to 14,800 doctors, only 2% of which were affiliated with the company.

UnitedHealth says Harmony shows how the company can work with its own doctors and select outside providers to lower costs and improve patients’ experience.

Physician groups in the Harmony network in Los Angeles County, Orange County, Riverside County, and San Bernardino County are all affiliated with UnitedHealth’s Optum or HealthCare Partners groups, the company said. In San Diego, physicians on the plan are affiliated with UC San Diego Health and Sharp HealthCare.

Smaller Networks

By working with a smaller network of providers, UnitedHealth can more smoothly integrate customer service, clinical care and data to improve patient experience, says Rob Falkenberg, chief executive of UnitedHealthcare of California. He said in other markets the plans may work with providers not affiliated with Optum.

“I hate to even admit to this but today, when you call -- this is pre-Harmony -- if you were to call a doctor’s office, they really don't know anything about the insurance coverage, and they don’t even know how to get that information,” Falkenberg said.

The new plan has a dedicated customer-service team. The providers have signed contracts where they receive a share of medical savings and are at risk for cost overruns. “We are sharing in the success or the risk, and so we are aligned in every way,” Falkenberg said.

He said both the insurance company and providers are accepting lower margins on the Harmony business. “The reason providers are willing to share in this commitment is we are able to get them more patients,” he said. “They see this as a way to grow their practices.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Drew Armstrong at darmstrong17@bloomberg.net, Timothy Annett

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.