No Tears for One Less $100 Billion Behemoth

No Tears for One Less $100 Billion Behemoth

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It took four years, two activists and a $30 billion acquisition, but United Technologies Corp. is finally breaking up.

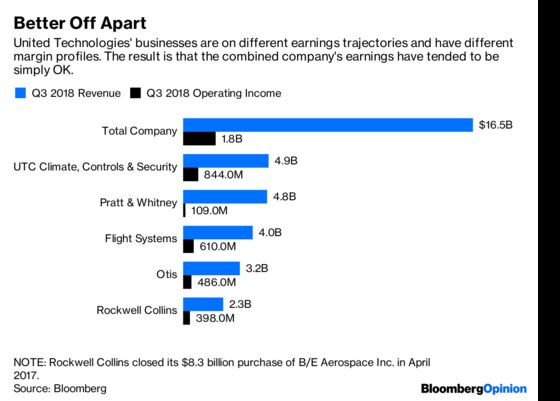

The industrial conglomerate announced late Monday that it will spin off its climate-controls unit and elevator business, leaving the company focused on Pratt & Whitney jet engines and the merger of its aerospace-parts division with avionics-maker Rockwell Collins Inc. That $30 billion deal also closed Monday after a drawn-out regulatory review in China, and was key to cushioning the surviving United Technologies aerospace business with the cash flow needed for expensive engine-development cycles.

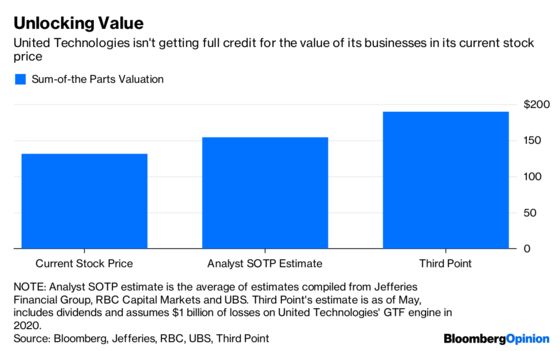

A debate over the merits of a grand shakeup has carried on in earnest since Greg Hayes took over as CEO of United Technologies in 2014. The situation eventually drew the interest of activist investors Dan Loeb and Bill Ackman, who both backed a split. And that’s because it makes so much sense.

United Technologies’ Carrier climate-control unit and Otis elevator division have little in common with its aerospace operations. The businesses have different capital requirements, growth profiles and debt capacities, and Monday’s breakup announcement is an acknowledgment of that reality. Splitting them up will give the new management teams flexibility to pursue the strategy that’s best for each individual business, rather than the conglomerate as a whole.

After previously pushing back on a split because he felt the cost of setting up independent companies was too high, Hayes has become increasingly vocal about the value of focused businesses, making this week’s announcement something of a formality. But the breakup roadmap he laid out may yet evolve. The benefit of the planned spinoffs is that they are tax-free to United Technologies shareholders. Recall, though, that the company was initially contemplating a spinoff of its Sikorsky helicopter unit before striking a tax-efficient deal to sell it to Lockheed Martin Corp. for $9 billion in 2015. Hayes mentioned that precedent in July, noting “all options are on the table.” I think that’s still true today.

The strong cash-flow trends at the Otis elevator business may appeal to private equity firms that see a path to reversing the unit’s margin underperformance and have the stomach to brave trade war side effects. A merger with the elevator units of Thyssenkrupp AG or Kone Oyj is another possibility, although a trickier one given the likely antitrust hurdles to consolidation among a small field of competitors. Within the climate-control division, United Technologies is reportedly in the final round of auctioning off its fire-safety and security business. That would create an essentially pure-play HVAC and refrigeration company that seems ripe for consolidation.

Johnson Controls International Plc recently struck a deal to sell its automotive battery business to Brookfield Asset Management Inc. for $13.2 billion. It will use as much as $3.5 billion of the after-tax proceeds to pay down debt, but kept open the option of using the rest to participate in deals for its remaining HVAC business. A deal with United Technologies’ Carrier unit seems doable from an antitrust perspective, and the companies may be able to structure a transaction as a tax-free Reverse Morris Trust, if they can sort out the ownership percentages. Lennox International Inc. CEO Todd Bluedorn has also been a proponent of consolidation and has said there may be a way to get a deal between his company and Carrier blessed by regulators.

The appeal of Carrier and Otis divestitures is that such transactions would likely close faster than the current 18-month to two-year timeline for spinoffs. Hayes wasn’t wrong that disentangling businesses that have been tied together for decades is complicated, even if he initially overestimated the costs. That kind of waiting game hasn’t been good for the stock prices of companies in similar situations, such as Honeywell International Inc., which spun off its turbochargers and consumer-facing home technologies businesses this year, or DowDuPont Inc., which is still working on a three-way breakup three years after announcing the merger that precipitated it.

On a final note, United Technologies’ breakup sounds yet another death knell for the conglomerate model and could cast a spotlight on other incongruous portfolios. Ingersoll-Rand Plc, which sells golf carts, fluid-handling products and power tools alongside its heaters and air conditioners, immediately comes to mind. Last year, CEO Mike Lamach echoed Hayes’s concerns about the hundreds of millions of dollars it would cost to replicate centralized functions for separate companies. Hayes, as we know, got over it. Lamach and other industrial CEOs should learn from his example.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brooke Sutherland is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals and industrial companies. She previously wrote an M&A column for Bloomberg News.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.