U.S. Wireless Envy May Drive Trudeau Response to Rogers Merger

U.S. Wireless Envy May Drive Trudeau Response to Rogers Merger

(Bloomberg) -- The fate of Rogers Communications Inc.’s $16 billion takeover of Shaw Communications Inc. may come down to which the Canadian government wants more: better wireless networks or lower prices.

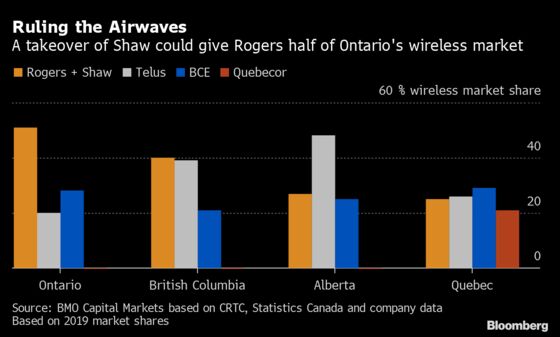

The transaction would reduce the number of wireless providers to three from four in about two-thirds of the country, according to BMO Capital Markets, potentially driving up consumer costs. It could also alter Shaw’s status as a low-cost alternative to the big carriers.

The companies, for their part, say the deal will allow them to spend billions on faster networks for remote regions and across the less densely populated west.

Most analysts expect the deal, which also includes the companies’ cable assets, to be approved by the government and regulators in 2022, but with stipulations. Here are the key issues.

Competition and Cost

To assuage antitrust concerns, the government is almost certain to force Rogers to divest some of Shaw’s wireless assets, which include a physical network, customer base and spectrum.

About 70% of Shaw’s wireless subscribers are in Ontario, and most of those are in the greater Toronto region, BMO telecom analyst Tim Casey said in a report. The merged company could have 51% market share in Canada’s largest province.

“We expect a much more contentious review of wireless” than any other part of the deal, Casey wrote, adding that Rogers might satisfy regulators by selling subscriber accounts and spectrum. “An outright sale of the Shaw wireless business does not seem obvious to us.”

Canadians have long bemoaned the cost of mobile services, especially as compared with their neighbors to the south. In 2020, the country ranked 209th in affordability out of 228 countries tracked by cable.co.uk. In Canada, the average price of 1 gigabyte of mobile data is $12.55, versus $8 in the U.S.

Geography is a big reason: Providing service to a country that’s larger than the U.S. but has 12% as many people is expensive.

Rogers and Shaw will need to show regulators some willingness to keep bills lower, according to Canadian competition lawyers who spoke on the condition they not be identified because their firms are, or expect to be, involved in the deal.

The companies could benefit from a provision in Canadian law known as the “efficiencies defense,” according to these lawyers. It allows merging companies to make the argument that synergies of a deal are so significant they outweigh any anticompetitive effects.

Spectrum

Shaw has benefited from a government policy that sets aside discounted spectrum licenses to regional players. The company was the third-largest buyer of 600-megahertz spectrum in 2019, spending almost C$500 million to win 11 licenses across the country.

The spectrum issue is politically contentious, and it’s not at all certain that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government would let Rogers, already Canada’s largest wireless provider, own licenses intended for smaller competitors.

Another question for regulators is whether Shaw should be allowed to participate in the auction of 3,500-MHz wireless spectrum in June, since the merger won’t be approved by then.

Rural Canada and the West

Infrastructure costs for rural and remote communities are high, and service can be poor. Fewer than half of Canadians in rural areas, and about one-third of indigenous communities, have access to high-speed internet, according to BMO’s Casey.

That’s a policy problem that Rogers and Shaw are promising to address. The deal announcement included pledges to spend C$2.5 billion ($2 billion) on 5G networks in the less densely populated western provinces and C$1 billion for connections in rural and indigenous areas.

Those promises -- along with commitments to add jobs and create a western headquarters for Rogers in Calgary -- could mitigate government concerns. Among other things, regulators will examine whether the companies can realistically deliver on those promises, according to one person with direct knowledge of the government’s thinking.

The process will probably force the government to review its policies on competition, according to competition lawyers, and that will take time. The companies themselves don’t expect the deal to close until the first half of 2022. That’s one reason Shaw is trading at a 15% discount to the takeover bid price of C$40.50 a share.

“This won’t come as a surprise to anyone but the success of this deal comes down to two things: affordability and jobs,” said Elliot Hughes, a former economic adviser in Trudeau’s government who’s now a senior public affairs adviser at Summa Strategies Canada Inc. and isn’t involved in the Rogers-Shaw deal.

“If the two companies are unable to demonstrate this merger will lead to lower prices for consumers and the creation of Canadian jobs, then it may face some raised eyebrows from regulators and officials,” Hughes said.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.