Trying to Shock Stocks With Emergency Cuts Usually Falls Short

Trying to Shock Stocks With Emergency Cuts Usually Falls Short

(Bloomberg) -- By definition, emergency rate actions don’t happen when everything is wonderful. The things they are intended to address have resisted an easy fix, and are often overwhelming. In the past, the celebration in markets was generally fleeting.

The Federal Reserve lowered rates by half a percentage point Tuesday -- the first reduction outside of a normal policy schedule since 2008. Anticipation of the move sent stocks up 5% on Monday. In its wake, they dropped 3.5%.

Of course, buttressing stocks isn’t the Fed’s mission, and every crisis the central bank was addressing with past measures eventually ended. But for anyone expecting markets to right themselves for good just because Chairman Jerome Powell is offering stimulus, history suggests otherwise.

“If you’re cutting rates intra-meeting, it’s because there’s an underlying crisis and monetary policy and rate cuts can’t address that crisis on a short-term time horizon,” said Eric Winograd, senior U.S. economist at AllianceBernstein. “I don’t think anybody really believes an intra-meeting rate cut solves the underlying problem.”

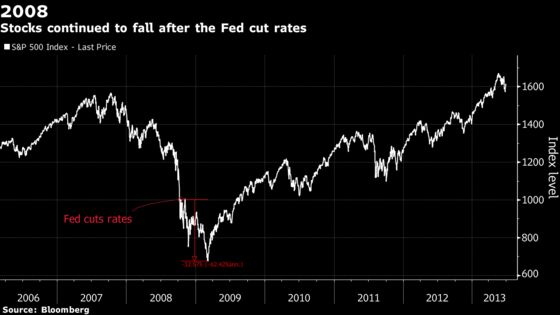

October 2008

As part of a coordinated action in the wake of the Lehman Brothers collapse, the Fed cut interest rates by 50 basis points on Oct. 8, 2008. The S&P 500 went on to plunge more than 30% before bottoming in March 2009, and the benchmark wouldn’t notch a fresh record high for another five years.

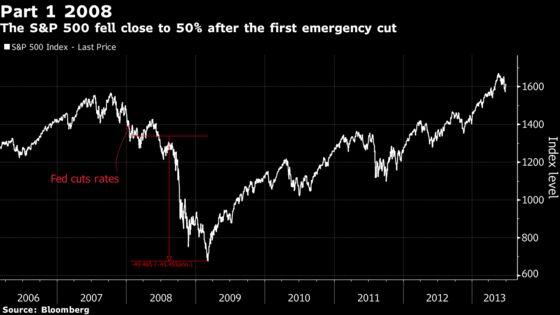

January 2008

The second of three such actions during the financial crisis came Jan. 22. From this point until the market bottomed, the S&P 500 plunged close to 50%. One year on from this date, the benchmark was still off by 37%.

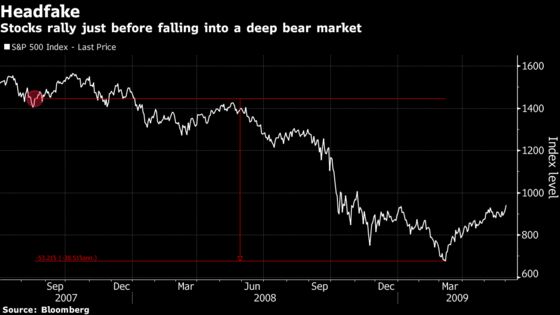

August 2007

The Fed cut rates by 50 basis points on Aug. 17, 2007. The S&P 500 first rallied 11% through early October, before beginning its slide into a bear market that wouldn’t bottom until the benchmark dropped 57%.

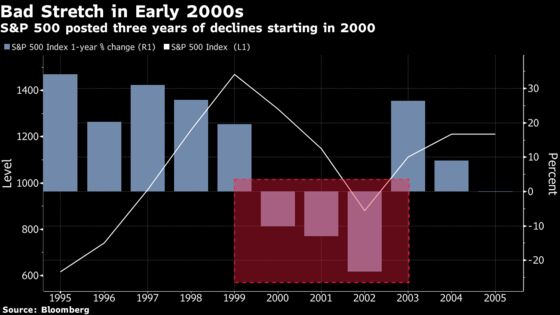

A Series of Three in 2001

The Fed cut its benchmark about a year after the bursting of the dot-com bubble, on Jan. 3, 2001, by a half-percentage point. Three-and-a-half months later, on April 18, the Fed lowered interest rates by the same amount once again. Then, on Sept. 17, days after the 9/11 attacks, the central bank once more issued emergency measures, cutting 50 basis points.

Before the first at the start of the year, the S&P 500 was already trading in a correction, off 10% from record highs. Stocks continued to tumble in the period prior to the April cut and fell further over the summer. While the S&P hit a low for the year four days after the Fed’s third reduction, the index still finished the year down 13%, its second straight annual loss. The following year didn’t see a turnaround, either -- the S&P fell more than 23% in 2002.

October 1998

The Fed introduced an unplanned cut of 25 basis points on Oct. 15, 1998, as Russia’s financial crisis and the collapse of Long Term Capital Management threatened a credit crunch. U.S. stocks had dropped nearly 20% over a six-week period in the summer of 1998 but the Fed’s intervention preceded a major rally that didn’t end until the bursting of the dot-com bubble in the early 2000s.

In 1998, the S&P gained near 27% and added an additional 20% in the subsequent year.

Last year, during a post-FOMC meeting press conference, Chairman Jerome Powell was asked about the Fed’s 1998 experience, including how the central bank was blamed for stoking the subsequent dot-com bubble. His answer focused on the Fed’s other tools for preserving financial stability.

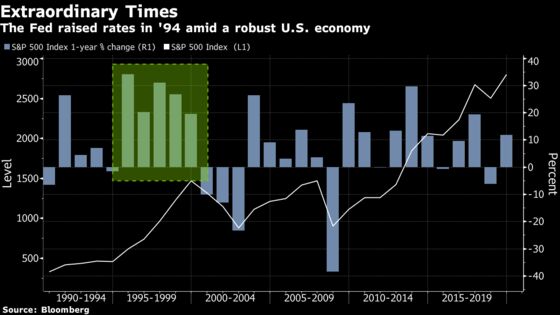

April 1994

Not every instance of extraordinary measures by the central bank amounted to interest rate reductions -- on April 18, 1994, the Fed increased its rate to 3.75% from 3.5%. It was the third hike that year meant to slow down a robust U.S. economy, whose growth at the time was notable for its lack of inflation.

Though stocks saw a slight decline in 1994, they rallied for the next five years. In 1995, the S&P posted its best annual gain over the last quarter-century, gaining more than 34%.

--With assistance from Simon Kennedy.

To contact the reporters on this story: Sarah Ponczek in New York at sponczek2@bloomberg.net;Vildana Hajric in New York at vhajric1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeremy Herron at jherron8@bloomberg.net, Chris Nagi

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.