Those Burgers and Tacos Are Actually Backing Bonds

Those Burgers and Tacos Are Actually Backing Bonds

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Wendy’s. Domino’s. Dunkin’.

Jimmy John’s. Taco Bell. Sonic.

Applebee’s. IHOP. Five Guys. Arby’s.

Chances are most Americans know at least some of these restaurant chains, if not all of them. Combined, they have more than 60,000 stores with hundreds of thousands of workers at their franchisees. They all have an operating history that spans more than three decades.

What’s perhaps less well known is that they’ve been something of pioneers on Wall Street. Together, they and others like them back the overwhelming majority of esoteric asset-backed securities known as “whole business securitizations,” which have quietly become a large and growing part of the structured-finance market. They ring of the kind of alchemy that contributed to the financial crisis, but they are likely to remain popular with yield-hungry investors.

The securities are about as straightforward as the name implies — franchise-focused companies sell virtually all of their revenue-generating assets (thus, “whole business”) into into bankruptcy-remote, special-purpose entities. Investors then buy pieces of the securitizations, which tend to have credit ratings five or six levels higher than the companies themselves, according to S&P Global Ratings. Creditors take comfort in knowing the cash flows are isolated from bankruptcy. The restaurants get significantly cheaper financing.

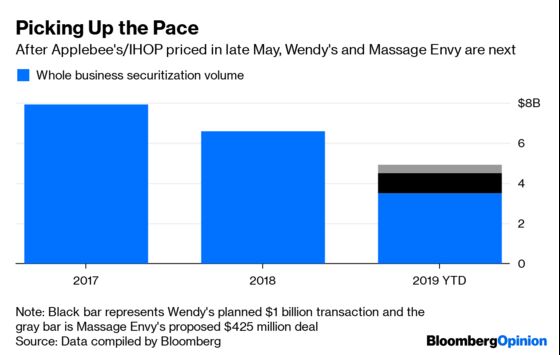

Cumulative gross issuance of whole-business securitizations reached about $35 billion at the end of 2018, compared with about $13 billion just four years earlier, according to S&P. The past two years have been banner years for the structures, with $7.9 billion offered in 2017 and $6.6 billion last year, according to data from Bloomberg News’s Charles Williams.

Things have been slower in 2019, though they look to be picking up. In late May, Dine Brands Global Inc., the parent company overseeing the Applebee’s and IHOP brands, completed a $1.3 billion refinancing of its senior notes from 2014. The Wendy’s Co. will be in the market soon, also to refinance a previous offering. And in a non-restaurant offering, private-equity-backed spa chain Massage Envy LLC is planning to sell $425 million in its inaugural whole-business securitization, Bloomberg News’s Claire Boston reported.

Wendy’s credit rating is five levels below investment grade from S&P and Moody’s Investors Service, yet its ABS are triple-B. That’s the same rating as Dine Brands got on its recent offering. “Dine’s asset-light business model provides us with access to the attractive securitization market,” Thomas Song, the company’s chief financial officer, said in a statement.

In the post-financial-crisis world, it’s easy to be immediately skeptical of anything that looks like a somewhat new and complex structured product. In reality, most transactions are done for smart and specific reasons.

Yes, whole-business securitizations have some downsides. As the name implies, going through with the transaction means those restaurant companies largely forfeit the opportunity to do any other borrowing — after all, virtually all of their cash-generating assets are promised to the SPEs. That means fewer options to weather any sort of sustained weakness in their business. At the same time, these are largely well-established brands. In fact, many could be considered recession-proof, given their low prices. Taco Bell’s tacos are $1.29, and at Domino’s, a large cheese pizza is about $10.

In writing about Domino’s securitization in 2017, The Wall Street Journal’s Ben Eisen smartly pointed out that “in some ways, the structure requires the company and investor to iron out what would happen to the debt in a hypothetical bankruptcy before the securities are even issued.” That pretty much summarizes why otherwise junk-rated corporate borrowers get bumped up to investment grade and their borrowing costs plummet.

The biggest risk in buying high-yield bonds is that the company goes into bankruptcy and stops paying its debts. S&P said in a February report that franchise-heavy businesses are strong candidates for this type of securitization because many individual stores would most likely continue operating even after the parent seeks court protection. Investors should have “confidence that the business’ assets will continue to generate cash following the manager’s filing, irrespective of who has claims to that cash.” There are no such assurances in typical corporate debt.

It’s possible that whole-business securitizations, like other feats of legal and financial engineering, will go too far. Perhaps a junk-rated company without the brand loyalty or name recognition of Dunkin’ or Arby’s will get through, run into financial distress and shut off the cash flow to investors.

Massage Envy, for its part, has been dealing with a series of sexual assault accusations against employees of certain franchises, which could damage the company’s reputation, according to Kroll Bond Rating Agency. It was founded in 2002, compared with the much longer track record of the restaurant chains. A portion of the sale may also fund a dividend payment to the company’s owners. On the other hand, it has more than 1,100 locations in 49 states, so it generally fits the mold.

It’s hard to turn down the yield pickup on these transactions. The average yield on a five- to seven-year U.S. corporate bond is 3.14%, Bloomberg Barclays data show. The average triple-B debt matures in 11 years and yields 3.74%. The Applebee’s-IHOP senior secured notes pay a fixed rate of 4.194% for five years and 4.723% for seven years.

That sort of spread probably shouldn’t exist in perfect markets. But, as Eisen reported, the transactions were popularized in the mid-2000s by Lehman Brothers, which used bond insurers to guarantee the debt. That’s a double-whammy of bad financial crisis flashbacks, even if the structures held up. Plus, the ABS world is small. Guggenheim Securities LLC in 2017 added three executives to its asset-backed bond underwriting team, including Anuj Bhartiya, who had worked at Lehman and helped with the whole-business securitization to finance IHOP’s acquisition of Applebee’s in 2007. Guggenheim is a book runner on the coming Wendy’s deal.

If the last few weeks proved anything, it’s that the days of interest rates marching higher are pretty much over. To capture extra yield, investors are going to need more options. Whole-business securitizations will surely be on the menu.

Per Dine Brands's statement: "The Class A-2-I Notes bear interest at a fixed coupon rate of 4.194% per annum, payable quarterly, and have an expected term of five years. The Class A-2-II Notes bear interest at a fixed coupon rate of 4.723% per annum, payable quarterly, and have an expected term of seven years."

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.