The Legal Discrimination Still Keeping LGBTQ People Out of Work

The Legal Discrimination Still Keeping LGBTQ People Out of Work

(Bloomberg) -- June’s landmark Supreme Court decision bars bias against most LGBTQ people at work, but it doesn’t end all legal discrimination that keeps them out of work.

For Kelly Jenkins, the most disheartening encounter she had after coming out as transgender happened not at her workplace, but at a clothing store. Jenkins, who was working as a teacher in East Tennessee in the 1990s, was shopping in the women’s section of a store when an employee told her to leave and called the police to escort her out.

“I didn’t know how to go get professional clothes anymore without fear of being outed, without fear of retribution,” she said. After being refused service at a restaurant, Jenkins said she also avoided networking and going out with co-workers. She eventually left education for four years but now is teaching in Massachusetts, which has statewide protections.

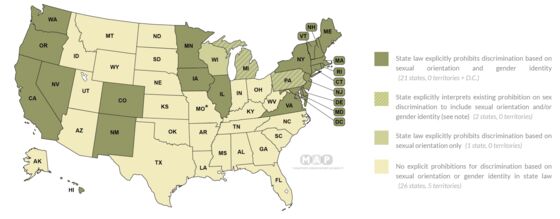

Tennessee is one of 26 states that offer no explicit state-wide protections for LGBTQ people in public places like buses, libraries, restaurants, stores and doctor’s offices, according to the Movement Advancement Project. Discrimination in these spaces creates hurdles for LGBTQ people — making them less safe, less healthy and less able to find work, said Avatara Smith-Carrington, the Tyron Garner Memorial law fellow at Lambda Legal, a civil rights group.

“You enter into a library with the hopes of using those resources to possibly look for a job,” Smith-Carrington said, “and you are harassed or discriminated against or denied access to that space — all of a sudden your ability to secure or apply for a job is cut down.”

Bias in public accommodations fuels the high rates of poverty and unemployment, according to Smith-Carrington. The Williams Institute at the University of California in Los Angeles reported in January 2019 that 9% of LGBTQ people were unemployed, compared with just 5% of the rest of the population. One in four LGBTQ people had a yearly income below $24,000.

There is no federal law prohibiting discrimination in public spaces on the basis of gender identity or sexual orientation. Many cities have nondiscrimination ordinances, but some states, like North Carolina, have passed laws to prevent local governments from extending such protections.

That means even emergency shelters, considered public accommodations in some cases, are not always a haven. Federally funded sites are prohibited from discriminating, but the Department of Housing and Urban Development recently proposed a new rule to allow them to discriminate against transgender people.

Debra Hopkins, a Black transgender woman in Charlotte, North Carolina, faced discrimination while experiencing homelessness between 2011 and 2013. She said that at one women’s shelter, the director told her she must submit to a strip search in order to stay – something that was not asked of any of the other residents.

She left the shelter and spent weeks sleeping on park benches and in a storage unit. Without a mailing address, it was nearly impossible for her to apply for and hear back from jobs. “From that point on,” she said, “I was never able to obtain employment again within corporate America.” Hopkins later founded and now directs There’s Still Hope, a nonprofit dedicated to providing temporary shelter for transgender adults.

Roberta Black, a transgender woman in St. Louis, said she faced harassment daily as she traveled to and from a vocational training program, including from bus drivers who intentionally misgendered and called attention to her. She started having panic attacks every morning before her commute. “Sometimes I would come home and cry a lot, but I didn’t have a choice,” Black said. “I pushed through as best I could and spent a lot of time thinking about ending it all.”

For many, the daily grind of discrimination begins before entering the workforce. GLSEN, formerly known as the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network, reported in 2016 that among LGBTQ students who gave a reason for wanting to drop out, over half said “hostile or unsupportive school climates were a barrier to completing high school.”

“What are the employment possibilities for somebody who may have had to drop out of school and get a GED because the school itself was not supportive?” asked Emmett Schelling, executive director of the Transgender Education Network of Texas. “And by ‘supportive,’ I really think folks need to understand this is just recognizing a child as who they are.”

Hopkins, the activist in Charlotte, said she was confronted repeatedly when she used a public restroom that matched her gender identity. “For a time, I stopped going into public accommodations and using facilities,” she said. That seemed easier than risking a scene, but it turned the fear of confrontation into a constant: “These things played havoc on me.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.