Templeton Loses Last Shot at Payments on Venezuela Warrants

Templeton Loses Last Shot at Payments on Venezuela Warrants

(Bloomberg) -- Franklin Templeton and other investors in obscure Venezuelan oil warrants just lost their last, lingering hope of a scheduled payment.

The zero-coupon notes, sold three decades ago, were supposed to pay their final biannual installment today. Except, of course, they didn’t.

Venezuela’s government is likely to claim that the slump in its oil revenue freed the nation of any obligations on the securities. Still, Nicolas Maduro’s regime, which started skipping payments on the warrants in April 2018, had discussed honoring the debt this time, according to people familiar with the matter. The idea was to garner good faith with creditors in the hope it would convince the Trump administration to ease Venezuelan sanctions, they said.

Those odds got dashed last month after the U.S. indicted Maduro for drug trafficking, offering a $15 million reward for information leading to his arrest. Meantime, the coronavirus pandemic knocked the oil notes down the priority list for both Venezuelan officials as well as their Wall Street counterparts.

Templeton’s London-based investment arm is one of the largest holders of the warrants, according to people familiar with the matter. Others include Morgan Stanley, Fidelity Investments and the West Virginia Investment Management Board, data compiled by Bloomberg show. Representatives at Templeton and Fidelity declined to comment, while officials at Morgan Stanley, WVIMB and Venezuela’s finance ministry didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Francisco Ghersi, managing director of Knossos Asset Management, said he didn’t receive payment on the oil warrants on Wednesday. In fact, the last time Knossos got any communication on the notes was when the government made its $74 million payment in October 2017, he said.

Initially, the oil-indexed payment obligations were a great success. Issued as part of the so-called Brady Plan in 1990, the notes began making payments in April 1996, which Venezuela touted in the back pages of the Financial Times.

There was just one glitch in 2004, after Hugo Chavez’s government fired striking executives from state-run Petroleos de Venezuela. The resulting chaos meant that the prices needed to calculate payments weren’t available, prompting a temporary default. But the government resumed payments soon after as its oil exports soared to a record, and by July 2008, the nation’s oil basket had reached an all-time high of $126 per barrel.

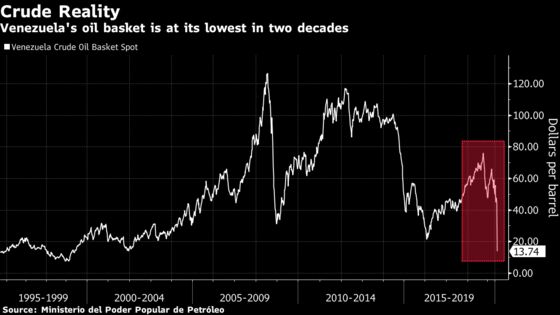

It’s been a bumpier road in recent years as government mismanagement, corruption and lower commodity prices sent the nation’s oil industry into a tailspin. Venezuela’s oil basket has since slumped to just $13.74 per barrel, the lowest since June 1999, according to the oil ministry.

Like most of the $60 billion in defaulted Venezuelan bonds, any legal tussle over missed payments will probably be lengthy. The U.S. recognizes opposition leader Juan Guaido as head of state, but Maduro still controls PDVSA as well as the oil and finance ministries in Caracas. Sanctions prohibit American investors from negotiating with most of Maduro’s inner circle.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.