Teenagers Are Driving Again. Watch Out!

Teenagers Are Driving Again. Watch Out!

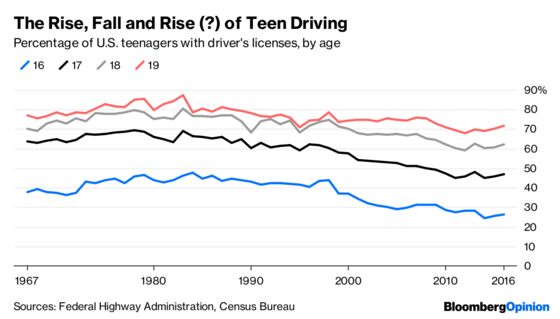

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Remember all those stories a few years ago about how American teenagers had soured on driving? They were based on real evidence: mainly a series of studies by Brandon Schoettle and Michael Sivak, then of the University of Michigan’s Transportation Research Institute, that among other things showed the share of U.S. 16-year-olds with driver’s licenses falling from 46.2 percent in 1983 to 24.5 percent in 2014.

Those numbers come from licensing statistics released annually by the Federal Highway Administration, which are currently available through 2016. And the 2015 and 2016 numbers show that teenage licensing rates actually bottomed out in 2014.

None of this changes the story that teenagers are much less likely to have licenses than they were in the 1970s and 1980s. Also, it’s not just teenagers: Members of every sub-50 age cohort in the U.S. are less likely to have a license now than in the 1980s. It makes sense to focus on the teens, though, since that’s when the initial decision to get a license or not is made. Why have they been choosing not to?

I first looked into these numbers after a colleague casually asked if maybe ride-hailing services such as Uber and Lyft were supplanting driving for teens. Uber first began offering rides outside San Francisco in 2011 but really only began to achieve critical mass nationally in 2014. So it can’t have played a role in the teen driving decline, and its continued growth since 2014 happens to have coincided with a rise in teen licensing. Maybe things have changed since 2016, as competitor Lyft has gained ground and several startups have taken aim at the under-18 market (you have to be at least 18 to establish your own Uber or Lyft account), but I wouldn’t bet on it.

The driver’s license decline also doesn’t appear to be due, at least not in a big way, to more kids growing up in cities and taking buses or subways to school. Apart from a brief turnabout right after the last recession, suburban counties have kept up their decades-long trend of adding population faster than urban counties. Public transit ridership in the U.S. did bottom out in the early 1970s, but its fitful rise since then hasn’t quite kept up with population growth, although there are some indications that transit use, biking and walking are up among younger Americans. Meanwhile, the percentage of students “transported at public expense” (taking school buses, mainly, although in some places like New York City students get transit passes) has actually fallen since the early 1980s.

Economic conditions seem like a more promising explanation. Licensing rates have long had a tendency to fall during and immediately after recessions, then recover somewhat when the economy is strong. That appears to be what’s been happening since 2014. Still, it doesn’t tell us much about the decline since the early 1980s.

One possibility is that for reasons other than cyclical ups and downs, fewer teens can afford cars. On the cost side, there doesn’t seem to be much reason for this: Cars are somewhat more expensive than they were in 1980, and insurance is a lot more expensive, but gasoline is cheaper in inflation-adjusted terms and vehicles are more reliable, too. Put it all together, and the per-mile average cost of owning and operating a motor vehicle calculated by AAA was lower in real terms in 2018 than in 1980 and about the same as it was in 1985.

On the income side, though, one can see big changes since the early 1980s. Here’s the percentage of Americans ages 16 to 19 who report either having jobs or actively looking for them:

If you don’t have a job, you’re both less likely to be able to afford a car and less likely to need one. This decline in teen labor-force participation and employment has been a much-discussed economic topic over the past few years. Some possible reasons for it seem positive: Far more 18- and 19-year-olds are in college now than in the 1980s. Others seem negative: Adults have been taking low-wage service jobs that once went to teens. Yet others involve cultural shifts that are neither obviously good nor obviously bad. In any case, the driver’s license and labor-force-participation trend lines do look so similar that they’re probably related. And the fact that the plummeting teen labor-force participation of the 2000s has given way to a modest upward trend would seem to indicate that the driver’s license numbers — which lag a couple of years behind the employment data — still have some increases ahead of them.

Schoettle and Sivak actually asked a few 18- and 19-year-olds in 2013 why they hadn’t gotten driver’s licenses. The answers were interesting, if not exactly dispositive:

The “too busy or not enough time” answer could mean lots of different things: that teens are in fact busier than they used to be, that they’re lazier than they used to be, that the perceived need for a license has become less pressing. It is undeniable, though, that getting a license takes more time and effort than it used to, and that once a teenager gets one, there are more restrictions on what can be done with it. States have also pretty much stopped offering free driver’s education in schools, and many have stopped offering it even for a fee.

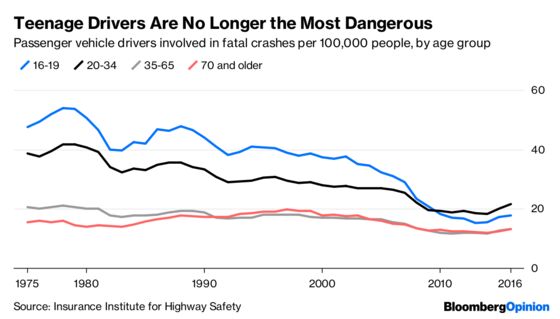

The driver’s ed cutbacks have been partly for budgetary reasons, but along with the new licensing restrictions, they’re also the product of a belief that teenagers are inherently bad at driving, as opposed to just inexperienced at it. There is some evidence for this, although accident statistics from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety also seem to indicate that delayed license-getting has shifted the age of greatest driving danger a few years later:

Also of note here is that, after decades of declines, traffic fatality rates have been increasing for all age groups over the past few years. This is probably mostly just because an improving economy has put more people on the roads. But another factor could become an ever-bigger issue in the years to come: There are more and more really old people behind the wheel in the U.S., and they’re terrible drivers.

When the Federal Highway Administration first started tracking driver’s license holders 85 and older in 1993, there were 1.4 million of them, or 40 percent of the age cohort. As of 2016, those numbers were 3.9 million and 60.8 percent. The fatal-accident rates per 100,000 people are now higher for 85-plussers than for those in their teens and early 20s, and it’s hard to see what could drive them lower, barring a licensing crackdown, until automated vehicles take over.

The percentages in the chart from 1978 onward are those from the annual Highway Statistics reports published by the Federal Highway Administration. Before then I took the annual numbers of licensees released by the FHA and divided them by Census Bureau population-by-age estimates. Those population estimates are as of July 1 each year and the license numbers are for the full year, which did some pretty funky things to the license-to-population ratios as the members of the first year of the baby boom (born in 1946) entered their late teens in the mid-1960s. (There were about 3.8 million of them, versus only about 2.8 million Americans a year older.) That's why I started the chart in 1967 rather than 1963, which is how far back the license data go.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, motor vehicles are cheaper now than they were in 1980 on an inflation-adjusted basis, but that’s because the BLS counts new features as quality improvements that increase the real value of a car even though they don’t make it any less expensive to buy one. The price of a Honda Civic started at $3,699 in 1980, which is $11,983 in 2018 dollars. The cheapest Civic now costs $19,450, but the cheapest Kia — which is perhaps a better parallel to a 1980 Civic — is $16,490.

Another possible factor is that big waves of illegal immigration in the 1990s and 2000s brought millions of people to the U.S. who in the vast majority of states are not eligible for driver's licenses.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.