Swedish Money Laundering Spins a Widening Web of Intrigue

Swedish Money Laundering Spins a Widening Web of Intrigue

(Bloomberg) -- As Sweden gets to grips with the money laundering scandal battering its oldest bank, questions are being asked about the impartiality of those overseeing the case.

Swedbank AB reportedly handled more than $10 billion in suspicious flows tied to the Danske Bank A/S Estonian laundering scandal. The case became public knowledge only this year, but according to Swedish media reports, employees at the Financial Supervisory Authority warned their bosses in 2018 that something was awry at Swedbank and recommended sanctions. None were imposed.

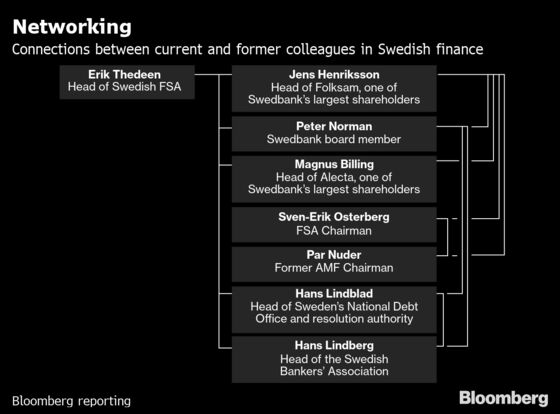

Concerns are now being aired in national newspaper editorials that old friendships and former career ties may have shaped the way the Swedbank allegations were handled by people at the nexus of power in finance, politics and regulation in a nation of 10 million. The case has already tarnished Sweden’s reputation as a paragon of probity and openness.

The bank’s alleged involvement in handling dirty money was reported in February by SVT, Sweden’s principal broadcaster, triggering a joint investigation by the financial supervisory authorities of Sweden and Estonia. The bank’s list of clients was said to have included deposed Ukraine President Viktor Yanukovych, who’s now in hiding in Russia. There are also concerns that Swedbank Chief Executive Officer Birgitte Bonnesen made misleading statements.

Louise Brown, a spokeswoman for Transparency International in Sweden, questioned the financial watchdog’s decision not to act sooner. She said having “close links” across the upper echelons of finance in a small country like Sweden “can result in a tendency to refrain from inconvenient criticism.” The “notion of mutual protection” that can develop may ultimately lead to corruption, she said.

FSA Director-General Erik Thedeen, who handed investigations into money laundering to his deputy because of his ties to a prominent Swedbank board member, also has connections with some of Swedbank’s biggest shareholders through his previous roles.

Career Links

Thedeen was a state secretary at the finance ministry when Swedbank board member Peter Norman was financial markets minister. In 2015, Thedeen was hired to work as CEO of a pension firm, KPA, by its chairman Jens Henriksson, who is now the CEO of Swedbank’s second-biggest shareholder, Folksam. Henriksson and Thedeen have both worked with Magnus Billing, the current head of the bank’s third-largest shareholder, Alecta. Henriksson was among shareholders who proposed appointing Norman to Swedbank’s board in 2016.

Thedeen “doesn’t participate in any meetings on any matter that concerns Peter Norman,” as he’s a friend, said Peter Svensson, press secretary at the FSA. He declined to comment further. A Swedbank spokesman, Gabriel Francke Rodau, declined to comment on the matter.

Billing said he’s confident that supervisory authorities have carefully examined any potential conflict of interest. He said his connections with Thedeen and Henriksson had no bearing on relations with Swedbank. Henriksson has a broad professional network, said Kajsa Mostrom, a spokeswoman for Folksam, and that’s both common and desirable for somebody in his position.

“Of course it doesn’t look good,” said Daniel Stattin, a professor in corporate law at Uppsala University. He said the problem is that “there are substantial connections” between the supervisors and those being supervised. “People have been each others’ bosses, or they have worked closely together.”

He said Folksam was “really fast in saying that they had no reason not to have confidence in Swedbank’s CEO and board." Across Sweden, Stattin said, revolving doors between high-level positions are part of the issue. “There is a considerable tendency among employees to go from the FSA on to the compliance functions of the banks,” he said.

Adding another dimension to the case, Sweden’s Economic Crime Authority last month started investigating whether insider information laws were broken after Swedbank gave its biggest investors -- representing about half the bank’s shares outstanding -- a heads-up on the February SVT report. That broadcast triggered a 20 percent drop in the bank’s shares.

A March 17 commentary article in Dagens Industri, the country’s main business newspaper, delivered a scathing judgment on the allegations : “Swedbank’s breakdown shows that Sweden is a country with corruption problems.”

The bank’s biggest shareholders will play a major role in deciding what happens next: The annual general meeting is March 28. There are already concerns that some major investors have been quick to exonerate Swedbank, despite the formal investigations. A report commissioned by the bank and published March 22 was supposed to address laundering allegations, but it left the public with more questions than answers. Sweden’s main shareholder association called the report “totally incomplete.”

The Dagens Industri article said ties between banks and those overseeing them are “so smudgy that it’s almost comical.”

“It’s not a given that these people let personal relationships cloud their judgment,” it said. “But that the question can be raised is troubling enough."

To contact the reporters on this story: Niklas Magnusson in Stockholm at nmagnusson1@bloomberg.net;Amanda Billner in Stockholm at abillner@bloomberg.net;Rafaela Lindeberg in Stockholm at rlindeberg@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Tasneem Hanfi Brögger at tbrogger@bloomberg.net, Paul Sillitoe

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.