The Stock and Bond Markets Can't Both Be Right

The Stock and Bond Markets Can't Both Be Right

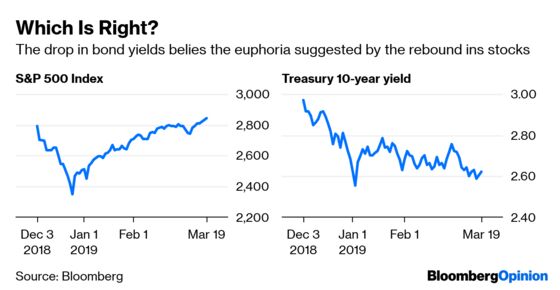

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The markets for U.S. equities and Treasury securities have diverged since Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and his fellow policy makers reversed course at the end of 2018 on the need for higher interest rates and the continued reduction in the central bank’s balance sheet assets.

The S&P 500 Index has risen 13 percent in 2019 on the idea that the Fed’s dovishness may allow the economy to sidestep a recession. Meanwhile, the yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury has fallen to below 2.60 percent. Also, the difference between two- and 10-year yields has remained little changed at an unusually tight 15 basis points. Simply put, the optimism seen in equities is not shared by bond traders. Historically, the bond market has had a better record of predicting the economy and, therefore, the divergence has important implications for investor asset allocations.

Specifically, recent developments suggest that the start of the next recession may be postponed to 2020 from later this year, and this provides room for further gains in equities. The bond market is signaling, on the other hand, that while the recession may be postponed, the risk has not been eliminated.

The widening gap in performance between the two asset classes is traceable to statements from Powell on two occasions at the beginning of the year. Perhaps rattled by the sharp drop in equities in the days following his hawkish comments on Dec. 19, where he suggested the need for two rate hikes in 2019 and a continued reduction in the balance sheet, Powell hinted on Jan. 4 that he would not hesitate to slow the reduction in the Fed’s balance sheet if necessary. He also signaled that there was no preset path for raising rates. The Fed provided more fuel for the rally in equities when it decided on Jan. 30 not to boost rates, and Powell suggested at a press conference that the central bank had reached the end of its rate hiking cycle.

Powell’s optimism on the economy did not, however, push up bond yields. While equity investors are reacting to indications that the Fed was attempting to reduce the downside risk in stocks, bond investors are focused on developments that point to a slowing of the U.S. and global economies. On the U.S. front, we learned just last week that:

- New home sales, after peaking in November, were lower by almost 15 percent in January.

- Orders for durable goods ex-transportation, a measure of investment spending, fell by 0.2 percent in January.

- U.S. manufacturing output fell in February for the second successive month.

- The core consumer price index (which excludes food and energy) rose by just 2.1 percent over the past year, belying repeated predictions by the Fed that inflation was headed upward.

Increasing signs of a slowdown led Chinese leaders to lower their economic growth expectations for 2019 to a range of 6 percent to 6.5 percent, from 6.8 percent in 2018, which was already the slowest growth in 28 years. While U.S. equities reacted to optimism that U.S. President Donald Trump and China President Xi Jinping could resolve their differences over trade before a proposed summit next month, holders of Treasuries worry that the two sides are far apart on structural issues and on verification.

In Europe, the U.K. has yet to resolve the terms of its “Brexit” from the European Union just days before the proposed separation date of March 29. Italy is already in a recession and the rest of the continent may soon be in one as well. The German economy faces risks due to the threat of Trump tariffs on automobiles and parts – the European giant’s single biggest export. German exports account for about 40 percent of its gross domestic product.

The resumption of geopolitical tensions increased demand for securities with haven-like attributes. Talks between Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un ended abruptly without an agreement, raising doubts on whether Kim would continue the moratorium on nuclear tests and the launch of missiles.

The takeaway for investors is that Powell realizes that even if the central bank were to increase rates just once in 2019, that could cause the yield curve to invert. And the Fed could even cut rates, or resume quantitative easing, if global conditions worsen more than anticipated. Equities that had been in a correction during the final days of December may again perform well for several more months with a benign Fed.

However, as the U.S. economy slows from an already weak first quarter and the combined weight of nine rate increases over the past three years, it would be time to reduce presence in equities and increase allocation to Treasuries. Equities are reacting to short-term optimism but the bond market appears to anticipate problems in 2020 and 2021.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at bburgess@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Komal Sri-Kumar is the president and founder of Sri-Kumar Global Strategies, and the former chief global strategist of Trust Company of the West.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.