Speculative Edge of Stock Market Is Where Rate Angst Is Biting

Speculative Edge of Stock Market Is Where Rate Angst Could Bite

(Bloomberg) -- Higher rates, are they good or bad for stocks? Nobody knows. But for edgier districts of the equity market where rock-bottom borrowing costs have provided years of cover, the early verdict isn’t good.

Consider the Russell 2000 Index of small caps, which a month ago was on pace for its third consecutive double-digit year despite the fact that a third of its members don’t make any money. Those shares have suddenly stopped outperforming as 10-year Treasury yields busted above 3 percent.

Drill down more and you can see how eight rate hikes from the Federal Reserve have altered the way investors view stocks. For the first time since 1999, companies whose bonds are rated junk have seen their price-earnings ratios slide to the same levels as those rated high quality, data compiled by Bank of America Corp. showed.

A basket of companies with stronger balance sheets compiled by Goldman Sachs Group Inc. is up 13 percent since December, compared with 7.5 percent for the weaker group.

The flip-flops highlight newfound caution among investors who for most of the past two decades embraced riskier companies, convinced they’d grow faster while falling rates kept solvency concerns at bay. While many consider higher bond yields a sign of a strengthening economy and therefore good news for equities, the shift in investor appetite underscores potential vulnerability at the speculative edge.

“If things turn over and interest rates are rising at the same time, that’s a toxic combination,” John Zaller, chief investment officer of MAI Capital Management in Cleveland, Ohio, which manages about $5 billion, said by phone. His firm recently trimmed some risky bets. “We’re not there yet, but that is something we’re certainly keeping an eye on.”

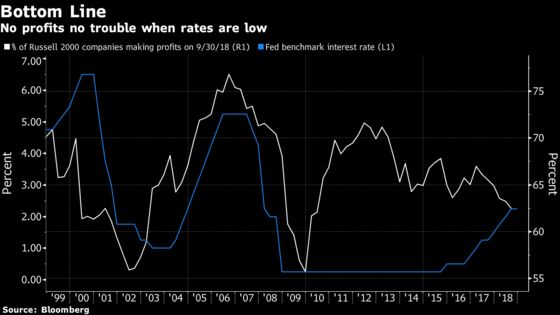

Investors have argued for years that a consequence of the Fed’s decade-long policy to hold down interest rates is the proliferation of unprofitable companies in the market. About 37 percent of the Russell 2000 members made no money in the past 12 months, the highest proportion in eight years.

While profitlessness is a trait investors are often willing to live with in growing firms, higher borrowing costs have not been a harbinger of well being in the past. A study by Leuthold Group showed that the number of money-losing firms has shown an inverse relationship with bond yields since the early 1990s. The lower the borrowing costs, the more unprofitable companies exist.

The real yield on 3-month Treasury bills peaked above 3.5 percent in 1998 and 2006, each time coinciding with troughs in the percentage of money losers, Leuthold found. While that kind of credit crunch still looks like a long way off, with the short-term Treasury bills yielding roughly the same as inflation, the danger for small-caps is growing.

“Rates have started to move higher quickly and so there is the potential that some companies will have more difficulty managing the increase,” said Kristina Hooper, chief global market strategist at Invesco Ltd. “Add to that, while the U.S. economy is strong right now, risks are increasing that could derail or at least slow the economy, making it far more difficult for companies to manage higher rates.”

Investors are taking notice. In the past month, the Russell 2000 has dropped more than 4 percent, compared with a gain of 0.3 percent in the S&P 500. It’s a turnaround from the first eight months of the year, when small-caps beat their larger counterparts by roughly the same magnitude.

“In a credit/debt dependent U.S. economy, and global economy for that matter, there is no greater input than the cost of money,” Peter Boockvar, the chief investment officer of Bleakley Financial Group, wrote in an email. “I have no idea when the next economic downturn comes but I’m very confident that when it does it will be triggered by a rise in rates that at some point hurts.”

It’s a departure from the early part of this bull market, when companies that score lowest in measures of financial strength consistently beat their sturdier counterparts. During the eight years from March 2009, the weaker cohort topped the stronger by 10 percentage points annually.

The preference to pay higher multiples on financially unstable companies, underpinned by rounds of fiscal and monetary stimulus in the 2000s and again this cycle, came to a stop as other central banks are poised to join the Fed in tightening, according to Savita Subramanian, BofA’s head of equity and quantitative strategy. Before 1999, high quality companies were mostly rewarded with a valuation premium, the firm’s data showed.

“The market has tried to get rational, each time thwarted by fiscal or monetary stimulus. The gap has finally closed,” Subramanian wrote in a note. “Tightening of credit favors continued re-rating of high quality stocks,” she said. “Investors should pay up for safety and be compensated for risk.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Lu Wang in New York at lwang8@bloomberg.net;Sarah Ponczek in New York at sponczek2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeremy Herron at jherron8@bloomberg.net, Chris Nagi

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.