There Are Signs Africa’s Market Rout Is Not Over Yet

There Are Signs Africa’s Market Rout Is Not Over Yet

(Bloomberg) -- Traders in African markets have had a year to forget, and there are signs the rout’s not over yet.

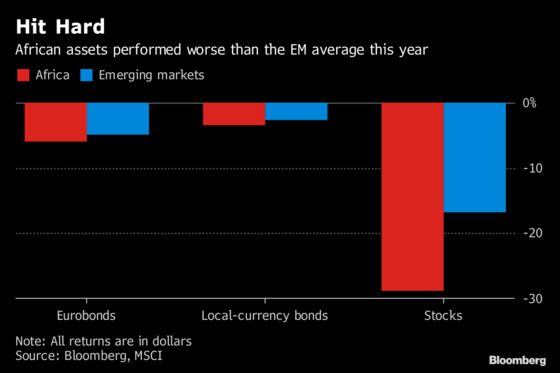

The continent’s stocks and bonds have performed worse than those of all other emerging-market regions in 2018, reversing their outperformance of last year.

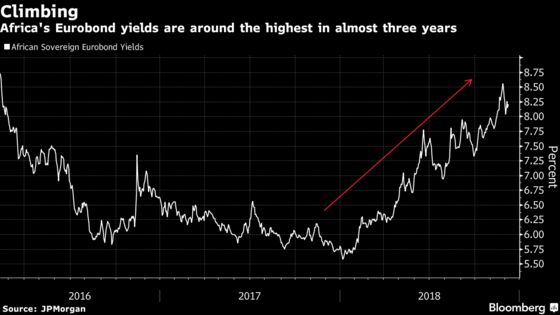

The sell-off has left equities in nations such as South Africa, Egypt, Nigeria and Kenya at or near their cheapest levels in years. And the yields of Eurobonds issued by governments have soared to a point last seen in early 2016, when investors fretted China’s economic slowdown was gaining momentum.

But bargain-hunters won’t necessarily jump in next year. Risks abound from tense elections in the two biggest economies -- Nigeria and South Africa -- to low oil prices, potential credit-rating downgrades and the prospect of sovereign defaults.

Here’s what investors should look out for:

Angola

The OPEC member is desperate to boost an economy that will contract for the third year running in 2018, according to the International Monetary Fund. This month, the government signed a $3.7 billion three-year loan with the Washington-based lender that it hopes will end severe shortages of foreign exchange, which have forced the central bank to devalue the kwanza by almost 50 percent against against the dollar since January. State energy company Sonangol, meanwhile, is trying to attract foreign investment in oil fields and increase production that’s at the lowest in about a decade.

Egypt

The central bank took a big step early this month when it ended a repatriation mechanism guaranteeing foreign-exchange availability for overseas investors. That will leave the Egyptian pound more exposed to market forces next year as bond and stock traders switch to using the interbank market. Their response so far has been “extremely positive” and few are exiting their positions, according to Citigroup Inc., which recommends that clients buy three-month T-bills yielding almost 20 percent. With a fiscal deficit of about 10 percent of gross domestic product, Egypt needs the investment.

Ethiopia

Abiy Ahmed has pledged a raft of reforms since becoming prime minister in April, including opening up the telecommunications and power industries to private investors. That could further boost an economy that’s already the fastest-growing in sub-Saharan Africa. Still, foreign-exchange shortages are acute, putting pressure on the birr. Issuing another Eurobond would increase the Horn of Africa nation’s low reserves, but the IMF warned this month that it’s at high risk of debt distress.

Ghana

West Africa’s second-biggest economy is set to exit a bailout program with the IMF at the end of this year. That’s helped fix the nation’s finances and drive the inflation rate down to its lowest since 2013. Still, investors are wary about the finance ministry’s plan to sell billions of dollars of century bonds and hope it isn’t a sign the government will revert to unsustainable spending without the guiding hand of the IMF.

Kenya

With growth of around 6 percent expected next year, the Kenyan economy remains one of Africa’s most buoyant. But Moody’s Investors Service has warned about the government’s rising debt levels and said they’ll probably reach 60 percent of GDP in the medium term. The IMF has also said that, due to central bank meddling, the shilling is almost 20 percent overvalued and no longer a floating currency, which Governor Patrick Njoroge has denied.

Mozambique

The southern African country may have been in default for almost two years, but its Eurobonds are the best performers in emerging markets in 2018, making a price return of 15 percent. Much of that’s down to the government agreeing, in principle, a restructuring deal with most of its bondholders. If other investors give their consent early in 2019, it could pave the way for Mozambique to get an IMF bailout, tiding it over until it starts exporting liquefied natural gas in the middle of the next decade.

Nigeria

Nigerians go to the polls in mid-February, with 75-year-old President Muhammadu Buhari trying to fend off a challenge from Atiku Abubakar, 72, a former vice president. Buhari says he’ll continue to fight against corruption. Abubakar’s long been dogged by allegations of graft. But many foreign investors think his policies -- including ending a system of multiple exchange rates and selling part of the state oil company -- are more likely to revive an economy still reeling from the 2014 crash in crude prices.

Senegal

The West African nation has presidential elections in late February but investors aren’t perturbed, given its history of political stability. That’s one reason, along with economic growth of 7 percent, why Citigroup says its Eurobonds could be in for a rebound after selling off heavily this year. The Wall Street bank’s analysts recommended to clients on Dec. 11 that they buy the government’s 2024 dollar notes, which yield 6.8 percent.

South Africa

South Africa faces a bumpy 2019, not least because of general elections in May. Should President Cyril Ramaphosa’s African National Congress fail to win a significant majority, he may be forced to delay market-friendly reforms such as revamping debt-laden state companies by retrenching workers or selling assets. Conversely, he could accelerate others that investors are nervous about, including changing the constitution to make land expropriation easier. Crucial, too, will be an assessment by Moody’s -- the last ratings company to judge South Africa as investment grade -- soon after the February budget. A downgrade to junk would trigger the country’s exclusion from the World Government Bond Index and outflows of as much as $7 billion, according to Citigroup.

Zambia

Next year could be make or break for Zambia, whose Eurobonds have tanked more than those of any other sovereign in emerging markets in 2018 and trade at spreads of around 1,200 basis points above U.S. Treasuries. Bank of America Merrill Lynch says there’s an “increasing risk” it’ll be forced into a debt restructuring if it can’t negotiate friendlier terms on bilateral loans from China or get an IMF bailout.

To contact the reporter on this story: Paul Wallace in Lagos at pwallace25@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Dana El Baltaji at delbaltaji@bloomberg.net, Hilton Shone, Robert Brand

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.