Rent Crisis Spirals for Landlords Awaiting $47 Billion in Relief

Rent Crisis Spirals for Landlords Awaiting $47 Billion in Relief

(Bloomberg) -- More than a year since Covid-19 lockdowns put millions of apartment dwellers out of work, almost $47 billion in U.S. government rent relief is hitting the streets. For many landlords, it’s coming much too slowly.

Joaquin Villanueva, an airport janitor who owns a three-unit rental house in East Boston, had to take out a home-equity loan just to pay the bills. One tenant, eight months behind on rent, vanished one night in March. An unemployed restaurant dish washer in another unit owes $5,000.

“I don’t want to lose my house so I’m doing whatever I have to do,” said the El Salvadoran immigrant who wipes the floors at nearby Logan International Airport. “I’m not rich like a Donald Trump.”

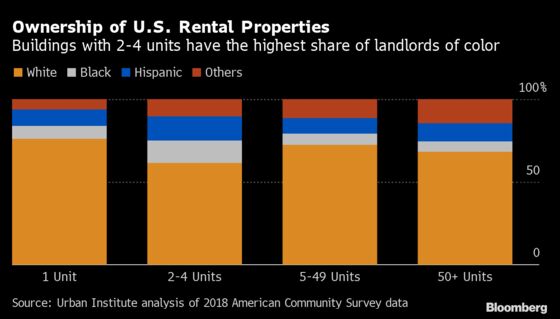

While the government passed sweeping measures last year to prevent mass homelessness among renters, there was no targeted help for mom-and-pop property owners who provide much of America’s affordable housing. Like their tenants, these landlords are more likely to be nonwhite or to be immigrants using real estate for their economic foothold. Now, mortgage, maintenance and tax bills are piling up, putting landlords in danger of losing their buildings or being forced to sell to wealthier investors hunting for distressed deals.

The tens of billions of dollars that Congress allocated for rent relief -- starting in December and then with a second allotment in March -- was supposed to help by covering back rent and unpaid utility bills. But the rollout has been moving at the speed of bureaucracy, which varies from state to state.

“The fact that we’re over a year into the pandemic really puts a lot of these landlords at risk,” said Rick Sharga, executive vice president at RealtyTrac, which provides property data for investors.

Rent shortfalls have drained owners and tenants of goodwill. But to save themselves, both sides will need to cooperate. Local governments, to prevent fraud, often require long, detailed applications signed by both parties.

There’s little data showing what share of landlords are in desperate situations, but it doesn’t take much to fall behind if income stops coming from one tenant in a small building. With each passing month, the problems get bigger and harder to solve.

Many landlords don’t qualify for federal Covid-19 mortgage forbearance, because less than a third have mortgages backed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac or another federal agency. And local governments can’t afford to forgo property taxes, especially in cities that have been hard-hit by the pandemic.

“The long-term concern here, over the course of a few years, is that a growing share of mom and pop landlords will be forced to sell and rents will go up,” said Peter Hepburn, an assistant professor of sociology at Rutgers University who researches housing inequality. “There’s a lot of private equity interest and a real possibility of growing consolidation.”

Lincoln Eccles, who owns a 14-unit building in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, New York, says he is flooded with unsolicited phone calls, texts and e-mails from investors. Selling would bring some relief -- the pandemic has put him a year behind on taxes and gas bills. But he’d like to pass the building, acquired by his Jamaican immigrant father, to his first son, born this month.

Still, headaches are mounting. One tenant owes more than $40,000 in back rent, five units are empty and Eccles can’t afford to replace or even fix a boiler that broke down again in March. The rent relief program will help only so much. He’s unlikely to get government grants to cover losses from a tenant who left in November owing $96,000.

Small owners are getting hit from many directions, said Roy Ho, who runs the Property Owners Association of Greater New York, which has 800 members who are mostly Chinese. Some also have retail businesses or are commercial landlords with stores, nail salons and restaurants now fighting to stay afloat.

Some of their residential tenants left the city during the pandemic, leaving vacancies, while others paid late or not at all, Ho said. The situation can get awkward when owners and renters live in the same building.

“It’s difficult to have a complete breakdown when one is living upstairs and the other downstairs,” he said. “But because of Covid, they talk less.”

Landlords are constrained by government bans from evicting tenants who missed rent during the pandemic. The federal moratorium will expire June 30, unless President Joe Biden extends it again.

Some property owners say eviction bans leave them saddled with tenants who were delinquent even before the pandemic. But many renters are in the same boat as landlords with debts mounting, said Cea Weaver, campaign coordinator for Housing Justice For All in New York.

“The eviction ban is a blunt instrument, but it’s needed,” Weaver said.

Even as the pace of payments pick up, other challenges are looming. The way Congress allocated the money gave an outsize share to smaller states with low renter populations.

New York’s $2.4 billion portion of the funds, for instance, is expected to cover less than 80% of back rent, utilities and late fees owed in the state as of March, according to estimates from Moody’s Analytics. In Illinois, it’s just 45%. Vermont, however, gets a roughly $350 million allocation, enough to pay for the state’s need more than nine times over.

While Congress provided the Treasury Department with authority to fix any mismatch in funding, the reallocation can’t happen for several more months.

Emergency rental assistance has been slow to get to tenants and landlords because it’s a massive undertaking that involves multiple layers of government, said Stockton Williams, the executive director of the National Council of State Housing Agencies.

Governments are trying to distribute a pot of money that’s far greater than the roughly $4 billion in rental assistance that some states and cities struggled to dole out last year. Now, they’ll have to comply with regulations that Congress set out over how the money can be spent, along with additional requirements they might have added.

“Standing up a brand new program like this that’s very high-touch and has to get out ASAP is really tough,” Williams said. A few states, including Alaska, Kentucky and Virginia, have moved quickly, he said. California and Texas, big states with big allocations, were slow at first but have picked up speed, he said.

Brandon McCall had to put his student loans in forbearance and cut back on groceries and other expenses after his condo tenant in Los Angeles fell behind on the $2,050-a-month rent. Now he’s pinning his hopes on the government. The tenant applied for rental assistance in early April, shortly after the city’s relief program began. But as of late last week, there was no answer.

“I lose money every month,” McCall said. “And I can’t even buy a place to live in myself.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.