Q&A: Neil Dutta on What the Consensus Is Getting Wrong About the Fed Right Now

Q&A: Neil Dutta on What the Consensus Is Getting Wrong About the Fed Right Now

(Bloomberg) -- For much of the last year, Neil Dutta of Renaissance Macro has been one of the most solid analysts on where the Federal Reserve, economy and market have been going. He’s been consistently bullish on the macro, bullish on stocks, and confident that the Fed would remain in an easy posture until it’s delivered on its new goals. Lately, some have argued that cracks are forming in the thesis. Inflation has run hotter than most economists anticipated. Job growth was also slower than expected last month. And some traders are now betting on some kind of hawkish turn from the Fed at this summer’s Jackson Hole meeting, perhaps in response to unexpected economic tightness. So I caught up with Neil over IB to get his full take right now on why he thinks the skeptics and critics are mostly wrong.

JOE WEISENTHAL: So to start, how would you see consensus about the Fed shifting?

NEIL DUTTA: I think the risks to the Fed call are far more balanced than Fed watchers appreciate. There seems to be a growing consensus that something big happens at the Jackson Hole meeting in late August. If this is the new baseline, then the risks are more dovish. There will be many questions still unanswered at that point. How many workers come back into the labor force following the expiration of UI, for example? We know the Fed's guidance is not just about inflation, it includes a very expansive view of what constitutes maximum employment.

JOE: Let's talk about the UI expansion/expiration for a second. In your view, how much do you think that is contributing to the slower-than-expected job growth that we saw last month? And more broadly, do you see the difficulty that some employers say they're having in hiring as a drag on GDP?

NEIL: I think it is an issue, but is it the main issue? I would argue no. In April, for example, we saw as many employed people not working due to illness as we did on average last summer. Covid-19 cases have been crumbling since the recent pick-up in April and that should show up in the employment figures in coming months. Importantly, we will get a quick test of this theory in coming months anyway. A number of states have moved to end the supplemental UI program early.

Is there a labor shortage? Yes. Job openings have exploded and the prime-age participation rate has not moved since last summer. But, why would this be permanent? The macro economy is normalizing. This includes Covid fading over time and the support programs also going away, as a result. If things are normalizing, then participation rates should too.

And, whatever drag we see on GDP is modest. What are people pointing to? A couple of data-points in housing? Auto production? What we are seeing, I would argue, is that the labor market has been healing somewhat more slowly than GDP, not that the labor market is a drag on GDP. The workweek is currently at levels we've never seen before (unusual because hours usually fall during recession). It is not sustainable.

JOE: So obviously in the near term, we do see significant inflation, and not just due to base effects. Again, this was all basically anticipated, and Powell has shown his inclination to wave it off. Have you been surprised, so far, by the unanimity that's been achieved among the FOMC members? Other than Kaplan, basically, the commitment to seeing it through and hit the aforementioned employment goals seems pretty consistent and strong.

NEIL: The only people that are not on board with Powell at this point seem to be Dallas Fed President Kaplan and Philadelphia Fed President Harker. Or should I say Fisher and Plosser? I think what has been more surprising has been the consensus' inability to just take Powell at his word.

JOE: To what do you attribute that, the failure to to just take Powell at his word?

NEIL: The consensus seems to believe that the Fed is following a similar script following the financial crisis. But, if they are, then what has really changed? The Fed started open-ended QE in September 2012, about nine months later the "tantrum" started, the Fed backed off in September 2013, and eventually did it in December of that year, about five quarters later. How is what people are talking about today any different? It isn't really and that's why I have an issue with it.

JOE: What about the idea, however, that the Fed is "fighting the last war?" We never had labor-market tightness or meaningful wage growth (particularly at the low end) post-GFC. This time we have it. This time around we have numerous companies talking about how they're swamped with demand. And furthermore, we've had much more aggressive fiscal policy, as opposed to a modest policy response that got turned off prematurely? Could it be that the Fed's new framework -- unveiled at Jackson Hole last year -- was an anticipation of an outdated fiscal policy response?

NEIL: "There are compelling reasons to expect the well-entrenched inflation dynamics that prevailed for a quarter-century to reassert themselves next year as imbalances associated with reopening are resolved, work and consumption patterns settle into a post-pandemic `new normal,’ and some of the current tailwinds shift to headwinds," Lael Brainard said two weeks ago.

We have to be open to the idea that the Fed's new strategy looks somewhat irresponsible in light of the economic data we are currently seeing.

We've had aggressive fiscal policy, but the excess saving rate is also quite high. So, I wonder how much of the current overheating is the result of demand dynamics related to fiscal policy. Rather, it looks like this is mostly about the supply curve being sticky in the short-run. The manufacturing supply chain is global in nature. We know that the rest of the world (EM) is having some trouble with Covid.

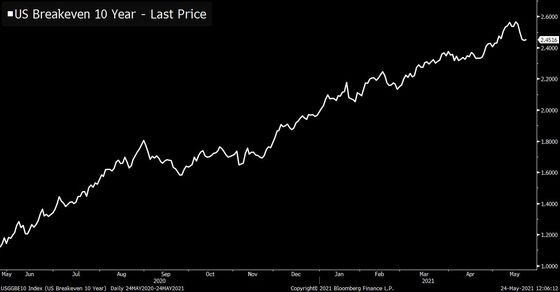

Also, breakeven rates have come down. The inflation data we have seen to date do not suggest that inflation is being driven by the kinds of sticky prices that ought to alarm the Fed but rather stuff like used cars and the reopening.

JOE: Good point on the breakeven rates having come down. It doesn't seem like that's gotten as much attention as the previous surge did prior to that.

NEIL: Why would it? The Fed is asymmetric and the consensus is too. The Fed is looking for reasons not to do something and the consensus is looking for the reasons for the Fed to pivot. I'll bet on the Fed.

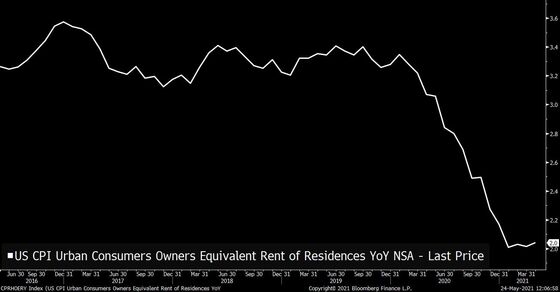

JOE: That being said, when you look at what's driving the inflation rate, you point to autos and other areas of supply chain constraints. However, Owner's Equivalent Rent hasn't bounced at all. However other housing measures have obviously soared. Do you expect that to pick up?

NEIL: Eventually yes. Some point to the idea that eviction moratoriums might be keeping a lid on OER and once they are lifted we could see OER accelerate sharply. But I think that is more of a 2022 issue. Of course by then, the prices for consumer durables will not be climbing as rapidly as they are now.

It’s also important to think about this in terms of asset-market effects and substitution effects. Home prices are surging and landlords obviously want to ask more of their tenants. But home prices are also up because demand for owning is up and that might weigh on the kinds of rents landlords can ask for in the short run.

JOE: Right. Great point. I've been wondering if perhaps we see some sort of dwindling of the renter pool, such that all these new homeowners don't have much pricing leverage over would-be tenants.

So looking ahead, where do you see the macro conversation a year from now?

NEIL: Good question. I think it can go in a lot of directions, which is to say I don’t know and I’m happy to admit that. I guess I’m worried about a couple of things. First, I wonder what return to work looks like. We’re not seeing people really go back into offices yet. What does that mean for the ecosystems of our cities? Second, we’ve seen a big drop in participation rates for those 55 and over. Are they coming back? The rise in teen participation rates would have to be enormous to offset the drop among that age group. And it’ll give a lot more fodder to the structural labor force woes people.

JOE: Great stuff Neil! I think that's a great place to leave it.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.