Public Pensions Face Reckoning From Equity Rout, Tax Losses

Public Pensions Face Reckoning From Dual Shocks of the Economy

(Bloomberg) -- U.S. public pensions suffered a double blow from the coronavirus pandemic: losing hundreds of billions of dollars in the equity market rout just as unprecedented revenue losses piled up for the governments that pay into the funds.

Funding levels will be under stress because of the losses in the financial markets, and at the same time, governments may struggle to make up the difference as the economic shutdown to stem the outbreak slashes their income.

In March, Moody’s Investors Service estimated that public pension investment losses were nearing $1 trillion. During the first quarter, the S&P 500 Index plunged the most since the Great Recession. Equity markets have since rebounded in April, and the Moody’s composite used to make the projection now implies returns of -9% instead of -21%, though the virus continues to inject jarring volatility into markets.

“Without a dramatic bounceback of investment markets, 2020 pension investment losses will mark a significant turning point where the downside exposure of some state and local governments’ credit quality to pension risk comes to fruition because of already heightened liabilities and lower capacity to defer costs,” said Tom Aaron, a vice president at Moody’s Investors Service.

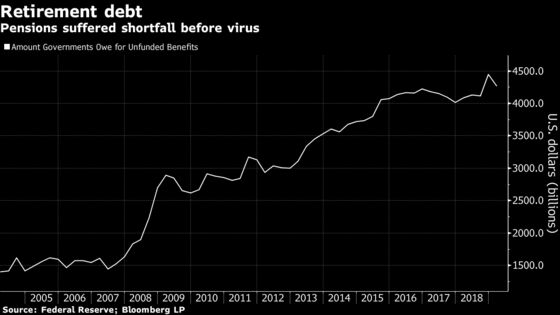

State and local governments had a combined $4.1 trillion in unfunded retirement liabilities before the pandemic hit, according to Federal Reserve data. While public pensions hadn’t fully recovered from investment losses and inadequate government contributions after the last recession, some states had made plans to put more into pension funds in the coming year.

Reduced Payment

New Jersey suffers one of the worst funded public pensions in the nation but the fund had recently made some gains. It held roughly $800 million more in cash at the end of February compared to the same time last year. Governor Phil Murphy’s proposed budget included a record $4.6 billion payment into the pension system, after years of skipped payments and underpayments.

That historic contribution, if paid, would still fall $1.5 billion short of the actuarial requirement. The fund did not respond to a request for comment.

“That payment will surely be reduced,” said Richard Keevey, who served as New Jersey budget director under Republican Governor Tom Kean and Democratic Governor Jim Florio, and the “shortfalls and the pension liabilities will increase.”

Keevey recently worked to help Democratic Senate President Stephen Sweeney craft a plan to cut the cost of public employee pensions and benefits.

On Wednesday, the New Jersey treasury department said it expects to see the impact from Covid-19 materialize in revenue figures next month, warning of a “significant impact’ on tax collections.

”We have extended the fiscal year in order to get a better handle on our revenue situation so that the administration and the legislature can map the best path forward to meet our obligations, which includes the state’s pension contribution,” said Jennifer Sciortino, a spokeswoman for the state treasury department.

Declining Revenue

In Illinois, Governor J.B. Pritzker’s administration had been working on plans to address its massive retirement debt, which has long been a drag on its credit rating, leaving the state only one level above junk.

Now, the state is facing a massive decline in revenue that could make it even harder for it make up the $137 billion owed to the state’s five retirement funds as of June 30.

In his 2021 budget address in February, Pritzker outlined his plan to use $100 million of proceeds from his proposed graduated income levy to pay down pension debt if voters approved the new tax structure in November. Jordan Abudayyeh, a spokesperson for Pritzker, didn’t immediately respond to emailed requests for comment. On Tuesday, Pritzker said Illinois is facing a “very, very difficult” financial challenge.

Painful choices

Public pension officials are watching their liquidity closely, hoping to avoid the painful decisions some funds had to make during the last deep recession in 2008 in order to pay bills like benefit checks for retirees and capital calls from investment partners.

“The biggest reason you need liquidity is to make sure you can pay the benefit payments that you’ve committed to paying,” said Kristen Doyle, head of public funds at pension consultant Aon Plc. “In this environment there’s a lot of uncertainty -- contributions that are expected from the employer could be stressed.”

Maintaining enough cash on hand is essential for a pension fund, especially during a downturn. It ensures funds won’t have to sell assets into down markets -- a fate the California Public Employees’ Retirement System fell victim to during the 2008 recession.

Calpers, the largest fund in the U.S., saw its daily market value plummet about 17% from more $402 billion in January to about $335 billion in mid-March. It’s since climbed to about $372.7 billion as of April 14. The fund learned from its 2008 experience, when it had to sell assets into plunging markets to meet capital calls, by shortening the period in which employers have to pay liabilities and calculating contributions more conservatively, said spokesperson Megan White.

The $53.6 billion Los Angeles County Employees Retirement Association has lost roughly 12%, or $7 billion, in market value since the end of December, though its sitting on $2.2 billion in cash, eight times its target.

“We’re very focused on our cash,” said the fund’s Chief Investment Officer Jonathan Grabel. “Cash is something that we’ve monitored and it’s something that we do on a daily basis at this point.”

Liquid Assets

Since that recession, many public pensions keep more cash on hand and lean more on government bonds that can easily be unloaded if markets go south, Doyle said. Even in a downturn, a combination of short-term holdings and cash flows are typically enough to get by, added Jean-Pierre Aubry, associate director of state and local research at the Boston College Center for Retirement Research.

That means for the most part, public pensions aren’t at an immediate risk of failing to make benefit payments, Aubry said. In a worst case scenario, they could sell assets if needed, he added.

“It’s important to recognize that the pension funding challenge is a long-term issue, not a short-term one,” Aubry said. “When the dust is settled, we’ll have to revisit the issue of pensions and serious questions will be asked about the future and financing of these plans going forward.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.