Princeton’s Scholarship Students No Longer Have to Fork Over Summer Earnings

Princeton’s Scholarship Students No Longer Have to Fork Over Summer Earnings

(Bloomberg) -- Princeton University gave a full scholarship to Marlin Gramajo, the daughter of a Los Angeles fast-food cook. But the school still expected her to chip in $2,000 from summer work and earn an additional $3,500 from campus jobs such as cleaning up the dining hall. That wasn’t easy.

“I had my shift, and I would stay up until 3 or 4 in the morning because I had a writing seminar the next day,’’ said Gramajo, 26, who graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 2016 and will attend law school this fall.

For generations, American colleges have required even the poorest students to pay something—or in the bland parlance of financial aid pros, make a “student contribution.’’ The idea was that everyone should have “skin in the game.”

Now, a few of the nation’s wealthiest schools are rethinking that approach because of fear that it is heightening inequality on campus. Even small financial burdens can put stress on students, who need the money for essentials or to help their families. It can force them to forgo extracurricular activities and unpaid internships and even to drop out of school.

Starting in September 2020, Princeton will no longer require scholarship students to pay the school, on average, $2,350 from their summer earnings. Undergraduates will still likely need to come up with $3,500 for books and other incidentals. This year, Princeton’s price is $73,000, though about 60% of undergraduates get financial aid.

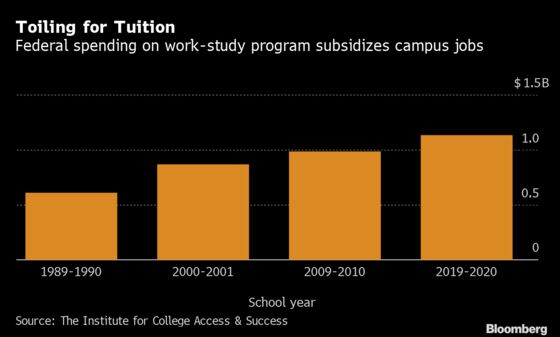

Scrapping the summer contribution is expected to cost Princeton $6 million a year—a lot for most colleges but not for Princeton. Its $26 billion endowment amounts to more than $3 million per student, the most of any major university. (The federal government spends $1.1 billion a year subsidizing work-study, but schools still pay some of the cost.)

“The great thing is we are able to do something about it,’’ said Robin Moscato, Princeton’s director of undergraduate financial aid. “It has a definite, direct impact on the student.’’

Similarly, Williams College is eliminating one of its four required summer payments, which average $1,500. For students on scholarships, Yale will pay for one summer abroad. Harvard recently started offering $1,500 stipends to incoming freshman who work at least 100 hours in public service jobs in their hometowns.

Some schools are helping with expenses that might otherwise have required poor students to work or borrow. In fact, at all but the wealthiest schools, colleges include loans in financial aid packages. In 2016, Harvard and Yale both said they’d give $2,000 grants to help the poorest first-year students with such expenses as books and bedding for their dorm rooms. In a pilot program, Brown this year is paying for the textbooks of 1,100 low-income students, mostly freshmen.

“These new policies have the potential to address some of the hidden inequities that trip up lower-income students,’’ said Anthony Jack, an assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and author of “The Privileged Poor: How Elite Colleges are Failing Disadvantaged Students.”

These shifts follow intensifying protest from students. This year, Yale undergraduates blocked a road to protest the school’s expected student contribution, which could be up to $5,950. (Yale, for its part, says it doesn’t bill students for that sum or require them to work for it.)

“No more income contribution,” the New Haven Register quoted them as chanting. “Let’s improve this institution.”

But others say even the poorest students should be expected to contribute some sweat equity to their studies, because a college degree carries great value that can pay off with a lifetime of higher earnings.

“There’s clearly a moral argument for saying, ‘If we're giving you money, you should be doing something in return,’” said Neal McCluskey, director of the Center for Educational Freedom at the Cato Institute, a Washington think tank that promotes limited government and free markets.“There could be mitigating circumstances that are important. But there's no such thing as a free lunch.”

Those who want to free up poor students from work requirements say times have changed. In the 1979-1980 school year, Yale charged $8,140 in tuition, room and board, or more than $28,000 in today’s dollars. Then, it was possible for middle-class kids to work a more significant chunk of the way through college. The cost now surpasses $70,000 a year.

In today’s economy as well, students often need internship experience to get decent first jobs. Low-paying or unpaid internships may not be an option for poor students who need to send that money to their colleges.

“It can be a huge obstacle for students who are trying to get ahead,” said Erica Rosales, executive director of College Match, a Los Angeles college prep program for low-income students that helped Gramajo and her brother, Eli, a 2019 Princeton graduate. “You come to these places because you want the networks. You want to have access and opportunity to careers that do provide a better life.’’

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Alan Mirabella at amirabella@bloomberg.net, John Hechinger

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.