Powell May Soon Have to Detail Fed Vision of ‘Inclusive’ Economy

Powell May Soon Have to Detail Fed Vision of ‘Inclusive’ Economy

(Bloomberg) -- Federal Reserve officials say they want to use monetary policy to promote an inclusive economy, but so far they’ve shied away from describing what such an economy might look like.

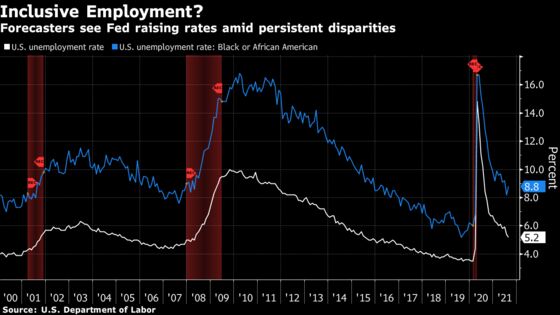

For now, forecasters say they expect the U.S. central bank won’t begin raising interest rates until 2023, when national unemployment will have sunk to 3.6% and Black unemployment to 6.1% -- roughly where those numbers were in early 2020, right before the pandemic struck. That’s according to the median estimates of the 16 economists who made predictions for both metrics in a recent Bloomberg survey.

But Fed Chair Jerome Powell, who is currently awaiting word from the White House about whether he will be reappointed when his term expires early next year, will get a chance to clarify whether those kinds of numbers would meet his definition of “inclusive” when he takes questions from reporters Wednesday following a two-day policy meeting.

“At some point, they can’t actually punt on the question of the Black unemployment rate,” said Claudia Sahm, a former Fed economist who participated in the survey. “The closer they get to liftoff, the more and more they are going to be forced to come up with something.”

It’s a key question for the year ahead as the U.S. central bank gears up to begin winding down the bond-buying program it launched at the onset of the pandemic in 2020, and then start raising its benchmark federal funds rate, which it slashed to nearly zero at same time. Two important developments since then have thrust Fed-watchers trying to predict where monetary policy is headed next into uncharted territory.

First, in August 2020 -- following a 20-month internal review of its rate-setting strategy and a wave of protests against racial inequality across the country following the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis -- the Fed redefined the “maximum employment” mandate that Congress gave it in 1977 to be “broad-based and inclusive goal.”

In other words, a low national unemployment rate is no longer sufficient for declaring “mission accomplished” -- Fed officials now want to see low-income communities benefiting from a strong economy too, something that only started happening at the tail end of the long economic expansion that preceded the pandemic.

The second development came a month later, in September 2020, when the central bank’s rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee announced that it expected to hold the funds rate near zero “until labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee’s assessments of maximum employment.”

That’s also different from the way the FOMC conducted policy in the past, when it sought to begin tightening monetary conditions prior to reaching maximum employment. The idea was to get out ahead of inflationary pressures that might be harder to subdue later on. In December 2015 -- when it first began raising rates after cutting them to near zero during the 2008 financial crisis -- the unemployment rate was 5% and Black unemployment was 8.5%.

But from 2015 to 2020, both overall and Black unemployment continued trending lower -- Black unemployment fell as low as a record 5.2% in 2019 before bouncing back to 6% at the beginning of 2020 -- and inflation remained tame. That experience led to regrets among Fed officials over misjudging the inflation threat and helped shape the outcome of last year’s policy review.

As of last month, national unemployment was 5.2% and Black unemployment was 8.8%. Both are expected to come down rapidly in the coming year as the economy recovers from the impact of the pandemic.

The big question now is whether monetary policy makers view the labor-market conditions that prevailed in early 2020 as representing the best possible outcome to hope for, all else equal, or if there is still room for improvement beyond that.

“Would they look back at February 2020 -- with the Black unemployment rate at 6%, and the country at 3.5% -- and say, that was an inclusive labor market? Because if that wasn’t an inclusive labor market, then that means, with monetary policy, when we get to February 2020 levels, we are not at ‘mission accomplished,’” Sahm said. “And if we are not at ‘mission accomplished,’ we should not be raising rates. But they haven’t told us.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.