Pay Gap for Working Women Keeps Wages Down for Everyone in Japan

Pay Gap for Working Women Keeps Wages Down for Everyone in Japan

(Bloomberg) -- In recent years, Japan has championed its growing number of working women as an answer to the country’s shrinking population and lackluster economy. But rather than feeling empowered, many are harboring a growing sense of inequity.

“I don’t think we’re being paid fairly,” said Sakiko Takasawa. As a care worker for the elderly, she’s part of a predominantly female industry paid far less than the national average. “There’s still such deep-rooted gender inequality,” added the 35-year-old, who was drawn to the profession during university as she watched her grandmother struggle with dementia.

While it’s globally common for salaries in female-dominated professions such as nursing to be lower than in mostly male industries, Japan’s gender pay gap, which measures the difference in wages between the sexes, is the highest among the Group of Seven rich nations.

Angst over pay disparity is running high in the nation as Prime Minister Fumio Kishida vows to revitalize the economy with his “New Capitalism” agenda of bolstering wages and distribution, and as Japan’s major employers and labor unions hold annual wage negotiations, called Shunto, in the next few weeks.

Takasawa counts herself lucky to be hired full-time, as a majority of women work part-time or on non-permanent contracts.

Daiji Kawaguchi, an economics professor at Tokyo University, said the gap was the biggest single factor in the country’s lack of wage growth over the past two decades.

“The rising number of women in the workforce has meant that wages don’t rise,” he said.

Kishida has called on companies at this year’s Shunto to agree to wage hikes of at least 3% after years of minimal or no increases beyond seniority-based raises. Yet economists doubt such government-led efforts will work, with companies likely to avoid costly hires amid worries over the pandemic and Russia’s Ukraine invasion.

Long Overdue

Few dispute that wage hikes are long overdue in Japan, with a labor market near its tightest on record and a working-age population now 17% smaller than it was in 1995.

In dollar terms, salaries in the world’s third-biggest economy have remained flat over the last two decades, while they rose 25% in the U.S. and 18% in France. South Korean workers have been earning more than the Japanese per capita since 2015, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Kishida’s call for wage hikes is also aimed at addressing criticism of his predecessor Shinzo Abe, whose “Abenomics” expansionist policies are seen to have led to a business recovery and benefited shareholders, but not the average worker.

The government blames stagnant wages for blunting the impact of stimulus measures, including the Bank of Japan’s massive monetary easing and repeated rounds of fiscal spending. Significant pay raises, policy makers say, would help to lift consumer spending, kickstarting a virtuous cycle of stable inflation and stronger domestic investment.

In addition to publicly calling on executives, Kishida has implemented additional tax breaks for those that boost employees’ wages starting this year. But less than 40% of companies pay the relevant corporate taxes to begin with, due to an array of tax avoidance measures. The majority wouldn’t see it as much of an incentive, economists said.

Some companies such as Toyota Motor Corp. have promised significant wage hikes after strong global sales. But a recent Nikkei survey of more than 6,000 companies showed 30% won’t raise pay at all, with most planning for wage hikes of far less than 3%.

A prolonged pandemic and a surge in energy prices heightened by the war in Ukraine mean companies are likely to continue hiring more non-regular workers, including part-time staffers and workers dispatched by third-party agencies, economists said. Such workers, who have few opportunities for training or career advancement, account for roughly 37% of the workforce, up from 29% in 2002.

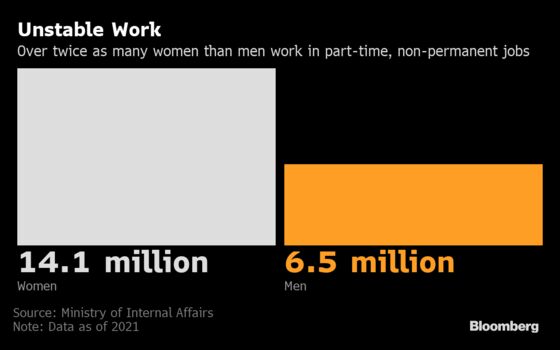

The rise of this new underclass of workers was helped by labor deregulation in the early 2000s and has overlapped with increased job participation among women. Last year, women took up more than two-thirds of these non-regular jobs, while only 22% of men are employed under such conditions.

“Because there was a rising number of women coming into the workforce, firms weren’t incentivized to push up wages,” said Kawaguchi at the University of Tokyo. Real wages, which account for inflation, fell around 6% between 2000 and 2017, and he estimates around two thirds of that decline was due to the gender gap.

To be sure, few fault Abe for advocating for more women in the workforce. Many women also prefer to work part-time, given Japan’s corporate culture in which overtime is normal and assignments to remote locations are hard to refuse for permanent employees. With women still taking on most of the housework and child care duties, many find it’s the only way to balance responsibilities.

Sonoko Tsukada, a 51-year-old mother of three and receptionist for an osteopathic clinic, is one of them.

“When you’re raising kids, you can’t do overtime, and you can’t work weekends,” said Tsukada, who used to be a full-time salesperson but now works three days per week. “My son did badminton in primary school and there were matches at weekends... I’m glad I was able to be there.”

Yet she, too, is not entirely satisfied, saying she’d like to put her English skills and study-abroad experience to better use one day. She also hasn’t had a raise for 10 years.

“Prices keep rising. Food, children’s lessons like swimming, they keep going up,” she said, adding that she’s tried to find full-time work with better pay but was finding it difficult at her age.

Mostly Male Unions

The increase in non-regular, part-time workers such as Tsukada has driven down union membership. Guild enrollment in Japan is now less than 17%, according to the labor ministry, falling gradually from a peak of 56% in 1949. It is even lower among women at under 13% -- a trend labor organizers hoped to change when picking Tomoko Yoshino as the first female head of the Japanese Trade Union Confederation, the country’s biggest union, last year.

Today’s unions are mostly cooperative with management, and wage negotiations are rarely combative as they were around the 1950s when Shunto, which means “spring offensive” in Japanese, began.

The collapse of Japan’s asset inflation bubble in the early 1990s also drove unions to focus on protecting lifetime employment and steady, seniority-based pay increases for members rather than agitating for salary hikes. That trade-off has helped the official jobless rate mostly stay below 3% throughout the pandemic.

Given the diminished impact of Shunto, Koichi Kurosawa, secretary general of the National Confederation of Trade Unions, said it was time to rally for an increase in minimum wage.

It’s not just union officials who say that raising pay for the country’s lowest earners would help close the gender gap and bolster overall pay. Michio Goto, professor emeritus at Tsuru University, said the current minimum wage of around 930 yen ($8) was based on the assumption that such pay was largely for women and thus supplementary to a household.

Kishida, sensing discontent among lower paid workers disproportionately affected by Covid-19, recently announced raises for public sector workers in nursing and daycare. That included a hike of 4,000 yen a month for nurses and an increase of 9,000 yen a month for elderly care workers.

Takasawa, who’s recovering from Covid after an outbreak at work, said she was unimpressed. Despite overnight shifts and physically exhausting routines, care workers’ monthly pay of around 240,000 yen is a third less than the average salary.

“Don’t be smug about a mere 9,000 yen hike,” she said. “It should be 10 times higher.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.