Opioid Settlement Encourages Sale of More Opioids, Critics Say

Opioid Settlement Encourages Sale of More Opioids, Critics Say

(Bloomberg) -- Purdue Pharma LP has proposed a settlement in bankruptcy court that could provide as much as $10 billion to help U.S. communities cope with the opioid epidemic. But for some states, the moral cost of accepting the deal is too high because it relies on even more sales of OxyContin, the highly addictive painkiller that helped create the public-health crisis.

The settlement offer calls for Purdue’s owners, the Sackler family, to pay at least $3 billion over seven years, with another $1 billion from current Purdue assets. The family, which amassed a $13 billion fortune, also would give up ownership of the company to a trust controlled by the states, counties and cities that sued Purdue, generating billions of dollars in additional income to be spent on treatment programs and law enforcement.

About half the states have agreed to the deal, saying the payout would help ease the burden on taxpayers. The other half said they’ll fight it in bankruptcy court. A judge must decide if the proposal is sufficient to absolve Purdue and its owners of liability from more than 2,000 lawsuits.

Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey, who sued Purdue last year and wants the company liquidated, said she’s concerned the settlement would be funded “by future sales of dangerous and addictive opioids.” She added: “I find that deeply offensive, and it certainly doesn’t qualify as accountability in my book.”

Many opponents of the settlement also say it falls short of the costs borne by U.S. communities and that the payout may be less than promised. They claim the Sacklers are getting off too cheaply and should pay a bigger financial penalty for their role in fostering an addiction epidemic that’s killed more than 400,000 Americans. But a distaste for the opioid business has emerged as potent stumbling block.

‘Not Enough’

“The proposed settlement amount is contingent on drug company proceeds, and I firmly believe that any settlement should not be based on profits from the sale of opioid products worldwide,” Letitia James, the New York attorney general, said in an emailed statement.

To be sure, OxyContin is a government-approved prescription drug, one of many opioids used by millions to manage pain. Given the medical need, supporters say, future sales of OxyContin won’t automatically be dirty money.

Purdue said the settlement filed in bankruptcy court Sept. 15 will benefit the public because it preserves the value of the company, which no longer markets OxyContin, and will include donations of addiction-treatment drugs and overdose medicines to communities across the U.S.

Purdue disputed the claim that the settlement would essentially put states in the business of selling OxyContin, because the company would be in the hands of a trustee, providing “multiple layers of governance insulating” the states.

“The framework absolutely does not call for state attorneys general to be in the business of selling opioids,” Josie Martin, a Purdue spokeswoman, said in a statement. “Once the plaintiffs appoint independent trustees and define the mission, they would be done other than receiving billions of dollars and potentially millions of doses of life saving medicines.”

“The debate over the opioid crisis has been often misleading and, in terms of providing solutions to the nation’s urgent public health needs, mostly unproductive,” the Raymond Sackler wing of the family said in a bankruptcy court filing. “The family is hopeful that Purdue’s filing and the proposed settlement can be a turning point in that debate and focus all parties on delivering real help where it’s needed -- in communities that are suffering.”

A spokesman for the Raymond Sackler family, as well as a spokesman for the Mortimer Sackler side, declined to comment on the objections to a settlement tied to future opioid sales.

Read More: Purdue’s Opioid Pact Unlikely Facing a Clear-Cut Bankruptcy Path

More than $4 billion of the proposed settlement won’t come from future OxyContin sales, at least not directly. In addition to the $3 billion promised by the Sacklers (likely from the sale of Purdue’s international opioid business), another billion or so would be cash from Purdue and possible insurance payouts, opposing state attorneys general contend.

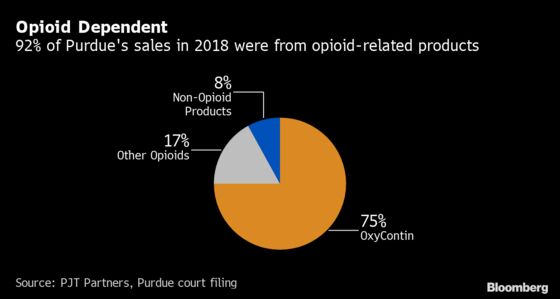

But Purdue’s own court filings suggest more than half of the proposed payout may come from selling more opioids, which remain “the vast majority” of its revenue.

Last year, OxyContin made up 75% of Purdue’s sales and opioids overall accounted for 92%, according to a bankruptcy court declaration by Jamie O’Connell, a partner at Purdue’s investment banking firm, PJT Partners LP. Development of new drugs could diversify the business, but are unlikely to generate any revenue before 2022, assuming they get regulatory approval, the filing says.

Opioid-related medications generated $975 million in revenue last year, down from about $2.2 billion in 2010, O’Connell said. The company expects sales to keep slowing, with this year’s total forecast at $644 million, and plunging to $82 million by 2024, as the patent on OxyContin expires.

‘More-Reasonable Prescriptions’

Purdue voluntarily halted marketing of opioids “so that even our toughest critics can rest assured that the business will operate in a manner consistent with its public mission.” In other words, future income will be based on more-responsible prescriptions and sales rather than the alleged abuses that were central to claims against the company.

Still, the trustees would run Purdue to generate money for the settlement, which means profit from OxyContin will flow to governmental plaintiffs.

Texas, Ohio and Florida are among those urging acceptance of the deal, saying it would provide immediate financial help in combating the addiction epidemic and get the Sacklers out of the opioid business.

“Any money that comes out of this is going to come from the sale of opioids, one way of the other,” Tennessee Attorney General Herbert Slatery said in an interview. “Getting money more quickly to deal with people dying is why we’ve decided to back” the settlement, he said. “We need more money now.”

Illegal Marketing

Purdue is one of more than two dozen opioid makers, distributors and pharmacies facing lawsuits by governments alleging drugs were illegally marketed to boost prescriptions, spurring a public-health crisis.

While improper OxyContin prescriptions have eased in the U.S., abuses still occur, and the problem may be widespread in other countries, according to several state attorneys general challenging the settlement.

“We have to answer an important question: What happens to OxyContin?” said Connecticut Attorney General William Tong, who opposes the settlement. “We do not know that yet. But any proceeds from the liquidation and distribution of that asset need to go to addiction science, treatment and recovery.”

“Going after the personal fortune of the Sackler family” would provide a “morally superior” alternative to the proposed settlement without the potential conflict of interest, said Joseph Carrese, a professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University’s Berman Institute of Bioethics in Baltimore. “This money already exists, and is not dependent on future sales of OxyContin.”

Some of the attorneys general opposing the deal also want an admission of wrongdoing by the family and the publication of internal documents that would reveal how decisions were made about pushing opioid prescriptions.

Alyssa Burgart, a Stanford University medical and ethics professor who prescribes OxyContin in her practice, said critics of the settlement may be overlooking the significance of getting the Sacklers out of the opioid business.

“I understand the attorneys generals’ reluctance to use money they see as dirty,” Burgart said. “At the end of the day, it’s better to have the states and other governments running Purdue to generate money for treatment than allowing the owners to continue to run it.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Erik Larson in New York at elarson4@bloomberg.net;Jef Feeley in Wilmington, Delaware at jfeeley@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: David Glovin at dglovin@bloomberg.net, Steve Stroth

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.