Once the World's Worst, Turkey and Argentina Bonds Are Leading the Pack

Once the World's Worst, Turkey and Argentina Bonds Are Leading the Pack

(Bloomberg) -- Turkey and Argentina have gone from dogs to darlings in the bond market.

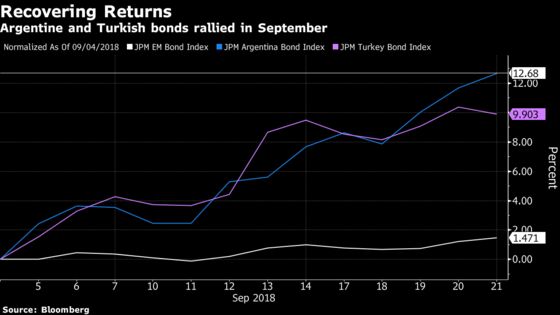

The rout that hammered their sovereign bonds last month is reversing amid signs that policy makers are taking concrete steps to right what’s wrong with their troubled economies. After being the world’s worst performers in August, notes from both countries are leading global gains in September even as concerns remain about details of the plans.

Argentina is working with the International Monetary Fund to repair its finances and Turkey has pledged support for its banks. But both countries are still burdened by massive current-account and fiscal deficits and inconsistent policy making that seemed to completely sap analysts’ confidence just a few weeks ago. The swing in sentiment highlights how much investors are willing to forgive when confronted with fat yields -- Argentine bonds pay 6.2 percentage points more than Treasuries and Turkey offers a 4.4-point spread.

“People are taking time to fundamentally go through the stories and making up their mind about whether they give credibility to the stories that the Turkish government and central bank or Argentine government and central bank give the investor community,” said Josephine Shea, a portfolio manager at Standish Mellon Asset Management in Boston.

Turkish bonds have returned 10 percent this month, while Argentina followed with a 9.9 percent gain, easily outperforming the average 1 percent advance for emerging markets. Meanwhile, Turkey led emerging corporate bonds, as banks Yapi Kredi and Isbank posted 20 and 19 percent returns respectively, trouncing the 0.8 percent index average.

The return of investors to countries that were among the worst performing bonds only a month ago comes as the governments of both nations take steps to contain the crises and traders return from a summer lull with a renewed risk appetite.

In Argentina, the government’s negotiations with the IMF for a bigger credit line are beginning to pay off. Argentina’s currency lost more than half its value in 2018, leading the government to seek a $50 billion loan and the central bank to hike interest rates to 60 percent -- the highest in the world. The IMF’s loan may increase by as much as $5 billion.

“The market was not expecting it,” said Shamaila Khan, director of emerging-market debt at AllianceBernstein in New York. “But that does help solve a lot of their funding issues for next year.”

Meanwhile, the Turkish Banking Association said Sept. 19 that banks accounting for 90 percent of total loans in the country have signed a restructuring framework agreement that aims to support companies struggling to pay debts. Investors have been concerned that banks could struggle to make payments on dollar-denominated debt after the value of the Turkish lira plummeted 38 percent this year, the second-worst performer in emerging markets.

A lack of clarity may damp investor confidence in the future of the economy. Few details are available for Turkey’s plan to support the banks. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s history of going head-to-head with markets -- once calling for the central bank to cut rates just hours before their eventual decision to hike -- has also made investors skittish.

“They might have an issue with restoring credibility,” Shea said. “It’s a very short-term question mark and it all revolves around the true willingness of the government to address the structural issues.”

In Argentina, where President Mauricio Macri says a revised IMF agreement will shore up investor confidence, it’s not exactly clear what would lure skeptics back. Even if Macri’s moves send the economy toward a recovery, tight fiscal policy could jeopardize his government’s chances in the upcoming elections, presenting a long-term risk for markets.

Argentina’s response was further clouded on Tuesday after the head of the central bank, Luis Caputo, quit after just three months on the job. He’ll be replaced by Finance Secretary Guido Sandleris, raising questions about the direction of monetary policy. The move generates uncertainty at a time when the country can least afford it.

For all the talk of renewed risk appetite, a resolution is far from certain for Turkey or Argentina, according to Shea.

“I don’t think we’ve seen the last of either story,” she said.

To contact the reporters on this story: Justin Villamil in Mexico City at jvillamil18@bloomberg.net;Alexandra Stratton in New York at astratton4@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Rita Nazareth at rnazareth@bloomberg.net, ;Jeremy Herron at jherron8@bloomberg.net, Brendan Walsh

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.