On Black Wall Street, Hope and Fear as Trump Comes to Tulsa

On Black Wall Street, Hope and Fear as Trump Comes to Tulsa

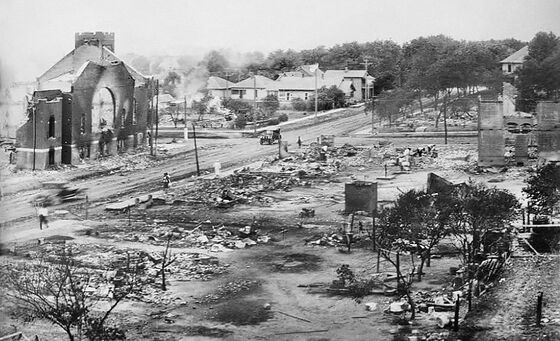

(Bloomberg) -- Little survives of Greenwood, the once-thriving neighborhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, that was burned to the ground by White rioters 99 years ago.

The area, known as Black Wall Street, was one of the most prosperous African-American enclaves in the U.S. before the slaughter of its citizens. Today, a mere handful of Black-owned businesses operate on its single remaining block. And with President Donald Trump about to descend for his first campaign rally in months, the hopes and fears of Greenwood — and Black businesses across the nation — have resurfaced.

Trump’s insistence on bringing thousands of supporters to Tulsa on Saturday has stunned many. After the coronavirus and nationwide protests over police violence, the spotlight turns to the place where mobs killed hundreds of Black people during the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921.

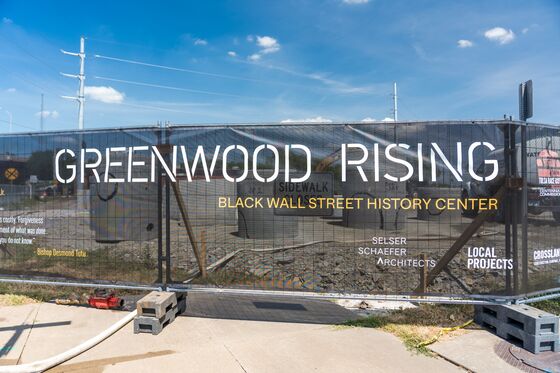

“It just feels like the perfect recipe for chaos,” said Venita Cooper, a former educator who last year opened Silhouette Sneakers & Art, a shoe store and gallery steps from where workers are building the Greenwood Rising History Center. “As a business owner, I’m hopeful. I want to show off Greenwood and Tulsa. I’m also incredibly scared.”

Trump has threatened violence against the left, tweeting Friday that protesters and “lowlifes” would be treated more harshly in Tulsa than in Minneapolis, Seattle and New York. “It will be a much different scene!” he wrote.

But Black business owners have spent weeks worrying that Greenwood, because of its increasingly well-known history, would become the target of White supremacists. During Black Lives Matter protests sparked by the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, rumors kept Cheyenne McKinney up at night.

“On Greenwood, the environment is such a friendly vibe. No matter what color you are, we’re going to say hi,” said McKinney, who opened Cheyenne’s Boxing Gym last year. But, as for Trump, she said, “he’s not welcome.”

Oklahoma’s Republican governor initially invited Trump to tour Greenwood, but later said he would advise against a visit. “Ultimately, the president doesn’t ask for permission before he comes to different places,” Kevin Stitt said.

Trump had planned to hold his rally Friday, which is Juneteenth, a holiday that celebrates the end of slavery. After an outcry, he rescheduled for 7 p.m. local time Saturday.

Greenwood’s own Juneteenth celebration had been canceled, but was quickly revived after Trump announced his visit, and activists plan a counter-rally in Tulsa’s Veterans Park.

“I want it to feel like a festival or block party, so we can ignore the fact that he’s here,” said organizer Tykebrean Cheshier, 21. “We don’t want to be so riled up that we forget to have fun and eat a hot dog.”

Protests in Tulsa since Floyd’s death have been mostly peaceful, with one jarring exception: On May 31, several were injured when a truck drove through a crowd of protesters marching on a highway to mark the 99th anniversary of the Greenwood massacre.

“All my years of life, I’ve never seen anything so visceral, so disturbing,” said Keith Ewing, a Farmers Insurance agent with an office on Greenwood Avenue. Nor do many Black residents count on their city for support.

In 2018, a Gallup poll commissioned by the city found 46% of Black respondents trust the Tulsa police “not at all or not much,” compared to 16% of Whites. Just 23% of Black residents agreed that the police department “treats people like me fairly.”

While segregation is no longer the law as it was in 1921, Black residents, who make up 15% of the population, predominately live on the north side. The city is also divided economically. The median Black family income in Tulsa County is $28,262, Census data show, about half that of the typical White family — a gap even wider than national disparities.

Indeed, in the U.S., the difference in wealth between Blacks and Whites has been largely unchanged in the past half century.

Only about a third of business loans sought by African-Americans are approved, compared with more than half for Whites. African-Americans are more likely to rely on personal wealth when starting a business, and home ownership -- a major mechanism of wealth accumulation and transfer -- also falls along racial lines. From 1983 to 2016, the Black home ownership rate fell, while Whites and Hispanics gained. Residential segregation, discriminatory pricing, and de facto redlining continue to this day.

During crises, such as the current coronavirus-sparked recession, those differences are most exposed. Nearly half of small businesses owned by Black Americans have closed — double that of White peers.

In the early 1950s, there were more than 6,000 black-owned grocery stores, said Maggie Anderson, a Chicago author who wrote “Our Black Year: One Family’s Quest to Buy Black in America’s Racially Divided Economy.” Now, there are about about 20. The steepest falloff began with integration, she said.

“African-Americans fought so hard for the right to be able to eat and shop wherever they want that we unintentionally abandoned our responsibility to maintain the community,” Anderson said. “We abandoned our perfectly top-quality department stores and restaurants and hotels.”

And then there’s Black Wall Street. More people, both in Tulsa and around the world, are now aware of the 1921 massacre, set off by the arrest of a Black man under dubious premises. White citizens rampaged, burning, looting and killing as many as 300 people. African-American citizens were rounded up and held for weeks.

After decades of being ignored or even suppressed, the massacre is now part of the state’s school curriculum — and last year was a pivotal plot element in the HBO series “Watchmen.”

Very little remains of the original neighborhood. Though survivors quickly rebuilt in the 1920s, much was later paved over by redevelopment schemes and a highway built through its heart. “They bounced back from the massacre, but they didn’t bounce back from urban renewal,” said Freeman Culver, chief executive officer of the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce.

A block-long stretch of businesses on Greenwood Avenue north of Archer Street is almost all that remains. In April, Culver’s Chamber was awarded a $500,000 grant from the National Park Service to help repair 10 buildings, which need new roofs, heating and cooling systems and brickwork.

“It needs to be a destination district. It needs to be filled with Black artists and Black entrepreneurs,” said Ricco Wright, the owner of Black Wall Street Gallery who is also running for mayor.

Greenwood is a short walk from a budding arts district that includes the Woody Guthrie Center and the future home of the Bob Dylan Center, scheduled to open next year. Both were bankrolled by Kaiser, who also helped finance the Gathering Place, a $465-million, almost 100-acre “park for everyone” along the Arkansas River in 2018.

Until now, protests seemed to be bringing positive attention, and customers, to Greenwood. Cooper, whose sneaker store was shut for months, recently reopened and found business better than ever. The “Buy Black” movement “has been very helpful,” she said.

Angela Chambers, who helped create the Tulsa Black Owned Business Network, said she wants the sentiment sustained long after the national focus has shifted.

“Our goal is to make a place where people can find products they’re looking for and support people who look like them,” said Chambers, 49. “We need to spend more money in the black community. We can’t go back to the old normal.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.