New Study Sheds Light on the Roots of Today’s Vaccine Hesitancy

New Study Sheds Light on the Roots of Today’s Vaccine Hesitancy

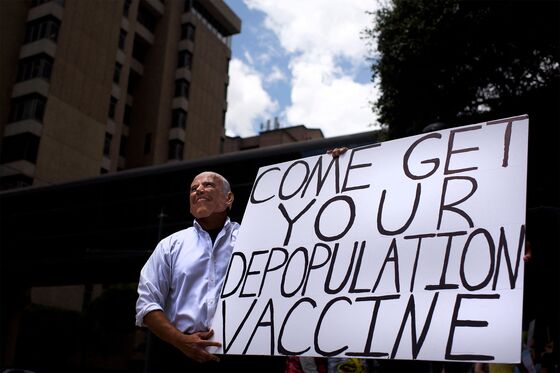

(Bloomberg) -- The anti-vaccine movement that has helped stoke widespread resistance to Covid shots has long been traced back to a single, now-retracted 1998 journal article linking autism to childhood immunizations. Now, a new study sheds light on just how much impact the study had, finding it led to a doubling of reports of side effects.

The discredited vaccine research and the rise to fame of author Andrew Wakefield have long been viewed as the beginning of suspicion of standard immunizations, which has blossomed in the coronavirus pandemic. Since the study appeared in the prestigious Lancet medical journal more than two decades ago, resistance to childhood vaccinations has grown steadily. The shots have been falsely linked to debilitating autism, mercury poisoning and other ills, despite study after study debunking those concerns.

Yet doubts about vaccines existed before Wakefield’s paper. The authors of a new paper published Thursday in the journal PLOS One asked, how much punch did one fraudulent scientific study really pack?

Quite a lot, as it turns out.

At a time when cases of autism were on the rise, the paper provided concerned parents with a much-sought explanation as to why. Even without the aid of modern social media, it went viral.

To gauge the change in public opinion before and after the paper, the study’s authors turned to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, a government-run, publicly available database where anyone can report possible side effects. Although entries in the database are unverified or fact-checked, it allows authorities to look for patterns and investigate if warranted.

Wakefield’s paper fraudulently suggested that the standard measles, mumps and rubella vaccine was linked to autism. Researchers led by Oklahoma State University political scientist Matt Motta combed through the VAERS database to see if there was an impact on reports to the database.

They found an immediate increase of about 70 MMR injury-claims cases per month after the paper’s publication. Before Wakefield’s paper, typically under 2,000 adverse MMR events were reported in the system each year. By 2004 it had more than doubled to over 4,000.

“The MMR vaccine is the same shot the day before Andrew Wakefield published this paper and the day after,” Motta said. “The chemistry of it doesn’t change. The administration practices don’t change. The only thing that changes is that we now live in a world where there’s media attention to the possibility that it might cause autism.”

The new study highlights not only the impact of the paper itself, but the role of scientists and the press today, as Covid vaccine hesitancy stands in the way of coming to grips with a deadly pandemic, Motta said. The Lancet was criticized not only for publishing Wakefield’s paper, but also for failing to fully retract it until 2010 despite concerns with the work that arose immediately after publication and multiplied significantly over the years.

Media’s Role

The press also played a significant role in bringing Wakefield into the spotlight, and keeping him there despite the controversy surrounding the work. For years after his study was published, Wakefield was a darling on the media circuit, his work receiving ample coverage in newspapers, his face appearing on the evening news and talk shows.

“When folks in the media give attention to academic studies that are controversial, that haven’t necessarily been been replicated in other formats, when we treat those things as gospel, we run the risk of creating a communication environment where people think that vaccines might be unsafe,” Motta said, “and that shapes the way that they interact with those vaccines.”

From early enthusiasm about treatments like hydroxychloroquine, to the widespread confusion about the effectiveness of masks, both scientists and the media have encountered challenges in delivering consistent, understandable public health messages about the pandemic. Early last year, for example, coverage of Stanford University research suggesting the Covid death toll may not be as bad as others feared helped fuel anti-lockdown sentiment.

“What this really underscores is that when a surprising study comes out that says something that nobody else in the literature had been saying before,” Motta said, “it is so, so important to contextualize it.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.