Muji’s Minimalist Aesthetic Is Too Easy to Knock Off

Muji’s Minimalist Aesthetic Is Too Easy to Knock Off

(Bloomberg) -- The retailer Muji became one of Japan’s most recognizable brands by selling simple, practical items that it hopes will last for decades. It turns out, though, that “less is more” has its limits as a business strategy.

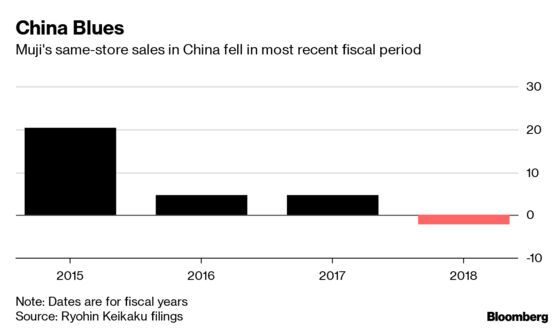

After a decade of expansion that brought its minimalist emporia of modular shelving, sturdy kitchen gear and earth-tone fashions to cities from Toronto to Shanghai, Muji is struggling. In April, parent company Ryohin Keikaku Co. reported its first decline in operating profit in eight years and a financial outlook below analysts’ expectations, as well as a rare drop in same-store sales in China.

Investors are worried: After the value of the company almost tripled from 2013 to 2018, Ryohin Keikaku shares have declined nearly 40% in the past year.

There’s more at stake than consumers’ ability to buy simply designed plastic folders and wastebaskets. With once-revered companies like Sony Corp. and Panasonic Corp. a shadow of their former selves, Muji is one of a small crop of Japanese brands that have succeeded in winning a worldwide following. Its potential decline doesn’t bode well for Japan Inc.’s ability to thrive in international markets; although its economy is the world’s third largest, the insular country has only one true global retail champion, Fast Retailing Co.’s Uniqlo.

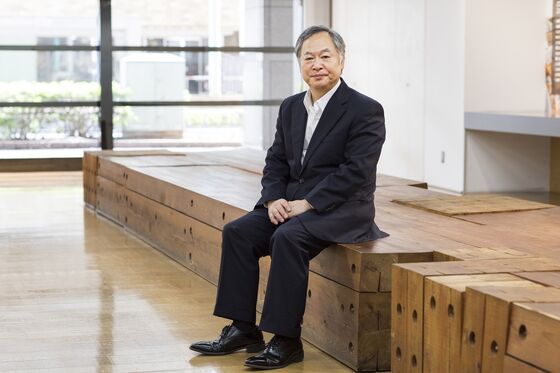

“I have a vision where in 2030, Muji stores are in most of the world’s major cities, and customers are buying the products and using it on a daily basis,” President Satoru Matsuzaki said in an interview at the company’s headquarters in northwest Tokyo, a nondescript building designed in the sparse, reclaimed-wood aesthetic sometimes known as “Muji style.” “For that, we need to break down and build up a lot of things.”

Matsuzaki, who spent his career at Muji opening stores from China to Kuwait, is hoping to navigate the retailer through global growth while also staying true to its original philosophy. In his four years at the helm, he’s embarked on new ventures like Muji-branded hotels and Muji-designed buses while pushing into new markets such as India and Switzerland. To drive growth, he’s now taking steps like shifting production to cheaper locations and designing products specifically for Chinese consumers.

Muji started in 1980 as a private label of the Seiyu supermarket chain, intended to offer a limited selection of low-priced products. (The brand’s full name, Mujirushi Ryohin, literally means “non-branded quality goods.”) At the time, Japanese consumers placed a premium on aesthetic perfection, and produce that didn’t meet exacting standards was often discarded. Muji went the other way: One of its first offerings was broken pieces of shiitake mushroom, sold at a discount—giving meaning to one of the company’s mottos: “lower priced for a reason.”

Seiyu spun off Ryohin Keikaku as a separate company in 1989, and Muji soon attracted a cult following in Japan, with product lines encompassing food, stationery, luggage and even furniture. Its products tended to remain unchanged for years, to underscore their functionality and sustainability. Items were designed in a minimalist manner that might delight the clean-up guru Marie Kondo: stackable drawers of differing width and height, but the same depth, or modular plastic containers for de-cluttering desks of pens, staplers and the like.

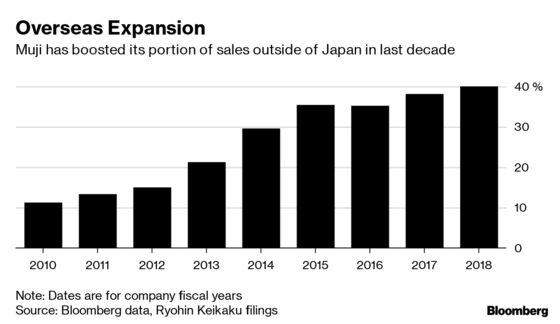

Although Muji’s first international location opened in London in 1991, aggressive international expansion only began in the 2000s, accelerating with a spate of store openings in China in 2012. Sales soared: Muji’s revenue has more than doubled since, to about 400 billion yen ($3.7 billion), and overseas stores now account for about 40% of overall sales.

Still, Muji’s forays abroad haven’t always hit the mark. It’s always expanded to other countries with the same items it sells at home, assuming that its product range needs little translation for overseas consumers. That works well enough for, say, pencil cases, but not necessarily other items: It took Muji a decade in China to introduce sheets that fit standard Chinese beds.

Meanwhile, Muji’s “no brand” branding and straightforward, unchanging designs have made it a prime target for low-cost Chinese copycats. Muji’s prices are considerably more expensive outside of Japan due to taxes and tariffs, and a cottage industry of Chinese competitors like Miniso, Nome and OCE has sprung up to offer the same aesthetic for a fraction of the cost.

A recent visit to one of Shanghai’s Muji locations illustrated the problem. A small notebook was selling for 25 yuan ($3.64)—a bargain, perhaps, but still more expensive than the 315 yen, or $2.92, that it retails for in Japan, according to its label. A portable fan was listed at 190 yuan, compared with just 39.9 yuan at Miniso.

“In order for Muji to be true to themselves as a provider of low-priced quality essentials, they have to bring down the price point and make it available to everybody around the world,” said Yoshinori Fujikawa, a management professor at Hitotsubashi University’s School of International Corporate Strategy in Tokyo.

To do so, Muji will produce more of its items in the countries where they’re sold. Next year, the company will roll out over 200 made-in-India products for its local stores. It’s also shifting more production to Southeast Asia, where labor is cheap. In China, it opened its first development office in September, with employees responsible for monitoring local lifestyle trends—a belated acknowledgement that Tokyo-based designers may not have the necessary insight into Chinese desires. Not everything will be internationalized, however. Muji will continue to make cosmetics, for example, in Japan, as the promise of high-quality raw materials is part of their allure.

“We have to sell products that are necessary or missing from Chinese consumers’ lifestyles,” Matsuzaki said. “Up until now, they’ve been buying us as a Muji brand, but now the time is coming where Muji is just a part of everyday life.”

Given how quickly its low-cost imitators have moved, Muji faces an uphill battle in China. And there and elsewhere, its ambition to become a global retail behemoth to match Uniqlo may require some of the strategic compromises made by other mass retailers—whittling its 7,000 products down to those of greatest sales potential, manufacturing items for speed rather than durability, and opening large locations in expensive shopping districts.

These steps may clash with Muji’s founding philosophy of simplicity and functionality, and risk putting off some of its fans, who are fiercely devoted to the experience of stepping into its botanical-scented stores and chancing upon items that are at once odd and practical, like right-angled socks or mattresses with legs.

Although it benefits from “a really good brand,” Muji’s aggressive expansion has created a complex set of problems, said Mike Allen, an analyst at Jefferies Japan Ltd. “They got their fingers in every single cookie jar in the world, and some of them have cookies in them, and some of them have rats,” he said. “I think they’ve bit off more than they can chew.”

Matsuzaki insists he can handle the balancing act required to turn Muji around. Though his ambitions are grand, he expresses them in characteristically restrained, Muji-esque terms. “We started in 1980 as a business from the broken pieces of shiitake mushrooms, but now we’ve become like one piece of tofu,” Matsuzaki said. “By 2030, we’d like to have the corporate value of two or three tofus.”

--With assistance from Jin Ye.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Chang at wchang98@bloomberg.net, Matthew Campbell

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.