Worst of Bond Selloff May Be Over, Morgan Stanley’s Sheets Says

Worst of Bond Selloff May Be Over, Morgan Stanley’s Sheets Says

(Bloomberg) -- The worst of the bond-market selloff may be over even though the Federal Reserve’s monetary-policy tightening is only just getting under way, according to Morgan Stanley chief cross-asset strategist Andrew Sheets.

Morgan Stanley recently closed the underweight bond positions it held since July, shifting to neutral after the 10-year Treasury yield soared past its year-end target of 2.6%.

Sheets estimates that the bond market has already priced in much of the impact of the Fed’s coming interest-rate hikes after Treasuries tumbled by the most on record during the first three months of the year. That’s made valuations more attractive just as the investment bank has become less optimistic about the U.S. growth outlook as consumers adjust to tighter financial conditions.

“We think bond yields can stabilize around the current levels,” Sheets said in an interview. “What’s already in the price matters. I can see a scenario where the Fed is being hawkish and is still hiking, but longer-dated bond yields don’t rise very much.”

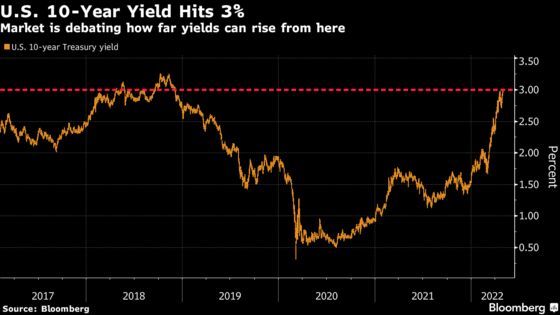

The 10-year Treasury yield has risen by nearly 1.5 percentage points this year as the market expects the Fed to move aggressively to tamp down the worst inflation in 40 years. The rate crossed 3% on Monday for the first time since 2018 and is holding around 2.92% Tuesday.

Even so, some analysts think bonds may continue to face pressure. Pacific Investment Management Co. said in its May asset-allocation report that it’s favoring stocks, anticipating that bonds still face “headwinds of high inflation, robust growth, and increasing government bond supply as central banks begin to unwind their balance sheets.”

The Fed is expected to raise its key interest rate by half a percentage point when it concludes its two-day meeting on Wednesday, which would mark the biggest rate hike since 2000. Policy makers are also expected to move toward trimming the central bank’s bond holdings by as much as $95 billion a month, a quicker shift than most forecast at the start of the year, and signal that more rate hikes will come over the rest of the year.

But a Fed decision to cut its bond holdings -- which will drain cash from the financial system as it stops buying new securities to replace those that mature -- doesn’t necessarily mean that yields will rise, said Sheets.

Rates came down in 2018 and 2019 during the Fed’s previous round of balance-sheet reduction, known as quantitative tightening, or QT. Conversely, yields rose during the central bank’s quantitative easing between late 2012 and 2013.

One possible explanation is that policy makers tend to resort to such bond buying during times of economic stress, when yields are low to begin with. As the policy eases that stress, yields move higher. QT takes place when growth is stronger and needs a tighter policy, which can result in slower growth that pushes down yields.

“There’s a paradox here over the past 10 years,” said Sheets. “The limited history that we have suggested that QE doesn’t necessarily mean go long duration and QT doesn’t mean be short bonds. It’s more complex than that.”

The swaps markets are currently pricing in that the Fed’s benchmark rate will peak around 3.4% in August 2023, up from a band of 0.25-0.5% now. This raises a question on whether the Fed can surprise the market with an even more aggressive pace of tightening without hurting the economy, Sheets said.

“That’s historically a pretty fast pace. For the market to be surprised, the Fed needs to do something even more than that,” he said. “Maybe the economy doesn’t have as much runway as it usually does.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.