Japan’s Government Bonds Have a Cute Sales Mascot, But Only One Buyer Matters

Japan’s Government Bonds Have a Cute Sales Mascot, But Only One Buyer Matters

(Bloomberg Markets) -- In the land that gave us Hello Kitty, it’s no surprise the Japanese government employs an endearing mascot to sell its bonds. His name is Kokusai-sensei. A pint-size rendition of him welcomes visitors to the investor relations office at the Ministry of Finance. Pudgy and professorial, he’s got his own Twitter account and stars in an online manga.

Yet this whole publicity campaign seems rather unnecessary. There’s just not much for Kokusai-sensei to do these days, thanks to the existence of a single, massive buyer of Japanese government bonds: the Bank of Japan. Why bother to encourage private investors to buy JGBs when the BOJ has been devouring enough of them to finance the bulk of the government budget deficit since Prime Minister Shinzo Abe took office in December 2012?

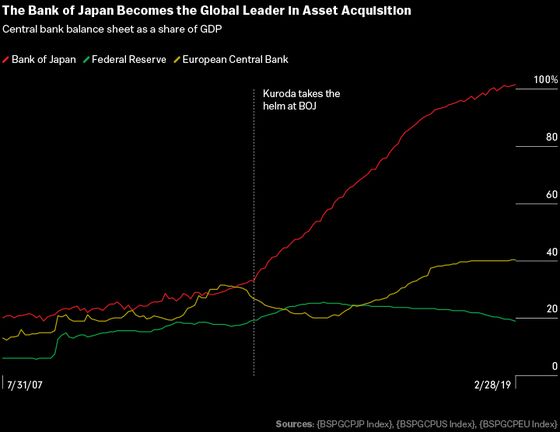

Japan’s central bank has clamped a tight grip on the bond market in an effort to pull down borrowing costs and inject massive liquidity—all to propel the nation out of the deflation and stagnation that took hold in the 1990s. It’s worked, up to a point. In recent years, BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda’s policy, backed by Abe, has helped boost growth and incomes in the world’s third-largest economy.

But the negative side effects of the Abe-Kuroda strategy are starting to pile up as investors and lenders increasingly struggle to cope with zero interest rates. Rock-bottom rates help sustain unproductive companies by shielding them from market forces. They also diminish the capacity of weak banks to absorb losses, especially regional institutions without nationwide networks.

It’s a cautionary tale for advocates of modern monetary theory who argue that countries can run up big public debt loads (and Japan has the biggest) with little negative consequence thanks to their ability to finance spending through central banks. Parts of the financial system are being driven to take risks they may not be prepared for.

“The real game changer will be when households take risk” with assets that now amount to about $17 trillion, says Shigeto Nagai, an economist who previously worked at the BOJ. The country is now in “kind of slow moving, chronic crisis,” he says.

Kuroda, even as he presides over the most extreme phase of a two-decade monetary campaign, seems to recognize this. Sort of. “I would like to pay careful attention,” he told Japan’s parliament on Feb. 13. But then he reiterated his commitment to the current stimulus program: “I believe it is my duty to stably achieve our 2 percent price target by continuing monetary easing persistently.”

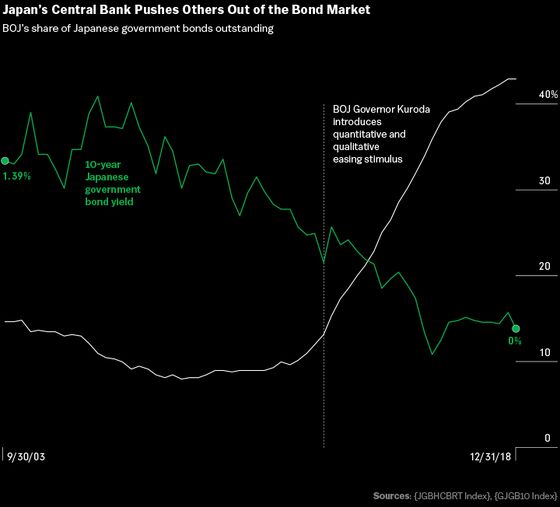

The BOJ has a 43 percent share of the entire JGB market, compared with a Federal Reserve share of U.S. Treasuries of just 14 percent. Japan’s policy enforces a yield curve that’s incredibly flat, ranging from a negative 0.1 percent on some very short-term cash reserves to about zero percent for 10-year JGBs.

The market is starting to show signs of worry. “There are huge risks to the banks from these kinds of policies,” says Heather Montgomery, an economics professor at International Christian University in Tokyo. Mizuho Financial Group Inc., Japan’s third-largest bank, went overseas to look for assets with higher returns. It didn’t go well. In its quarterly earnings announcement on March 6, Mizuho disclosed 150 billion yen ($1.4 billion) in losses on overseas bonds.

Other analysts and practitioners agonize over the notion that the BOJ has neutered the bond vigilantes who are supposed to safeguard the economy when governments and central banks act irresponsibly. If the central bank has a monopoly on JGB purchases, the bond market can’t punish the government for running up the world’s largest public debt load—more than 230 percent of gross domestic product—or force politicians to pare back borrowing. “For fiscal policy to be properly implemented, we need market discipline to fully function,” says Kazumasa Oguro, a Hosei University economics professor who previously worked at the Ministry of Finance. “But because the BOJ is flattening yields, that function is constrained.”

Japan’s policies are a kind of in vivo experiment for other advanced economies that only more recently began to confront deflation and an aging, shrinking population. So the rising voices of concern about its unorthodox remedies could hold lessons for policymakers considering prolonged asset-purchase programs in any future downturn.

Bond 350 began life in March 2018 as a 10-year JGB, the benchmark for long-term borrowing costs in Japan. It’s a direct descendant of Bond 1, which was sold in 1972. As of Feb. 20, the BOJ owned 88 percent of the 10 trillion yen of Bond 350 outstanding. It’s likely other public Japanese institutions—such as Japan Post Holdings Co., the country’s second-largest holder of deposits—own slivers of the remainder of Bond 350. Those stakes aren’t disclosed, but those investors typically hold such bonds for regulatory reasons. That leaves precious little for other investors.

Montgomery has been observing the financial and economic challenges for more than two decades. During a 1997 internship at Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan, she was surprised to find the state-backed lender embroiled in a battle with bad loans. LTCB, which collapsed the following year, was symptomatic of Japan’s financial and economic demise, which forced the BOJ into unprecedented action. It drove interest rates down to zero and after that provided liquidity by buying assets.

With little progress to show by 2013, when Kuroda took the helm, the central bank doubled down. Literally. The gamble was to double the supply of money in two years through bond purchases, generating an inflationary jolt that would set the economy on a sustained and faster path of growth.

“It is too bad they didn’t do it more aggressively, earlier,” Montgomery says. After all, Japan had been more forceful in the past. In November 1932, legendary Finance Minister Korekiyo Takahashi oversaw sales of government bonds to the BOJ to boost liquidity and pull the economy out of the Great Depression. Which it did—years before President Franklin D. Roosevelt oversaw reflationary policies in the U.S.

Takahashi’s experiment ended badly despite its early success. Once the economy was on the mend, he attempted to restore fiscal discipline. But the country’s ascendant military was determined to keep boosting BOJ-financed spending. Extremist officers assassinated him.

After World War II, the BOJ was banned from buying JGBs directly, except in extraordinary circumstances and with parliamentary approval. That’s because some economists regard direct purchases as debt “monetization,” which could undermine confidence in the stability of the yen. Today the BOJ buys bonds only in the secondary market, not directly from the Ministry of Finance.

Even so, it doesn’t wait long. By the end of the first month of Bond 350’s existence, the central bank had consumed 11 percent of the amount outstanding. By late May 2018, it had taken up about half—another step toward completing its mission.

Over the course of three decades, Susumu Kato has been watching the bond market up close. Now a consultant, he’s held roles including chief Japan fixed-income strategist at the former Lehman Brothers and chief Japan economist at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. With the BOJ hoovering up so much of the government’s new issuance over the past several years, he says, bond dealers have been left with little to do. “They just go to the JGB auction and bid as the primary dealers are required to do, and then turn around and sell to the BOJ,” he says.

Kato says some of his bond-dealer contacts have lost their jobs because of diminished volatility. There’s just not that much demand anymore for experienced, highly compensated dealers who can arbitrage anomalies across the yield curve and trade futures and interest-rate derivatives.

Since long before Kuroda became governor, traders have griped about the BOJ big-footing the market. But the noise level soared as Kuroda boosted bond purchases to an annual target of 80 trillion yen a year. As the industry has repeatedly made clear in meetings with the central bank, according to minutes of those sessions, nothing seemed to matter anymore: Whether the economy was strong or weak, whether stocks were tumbling or soaring—these factors have had little bearing on Japan’s bond market. Economic indicators can come in hot or cold; yields won’t move. The so-called price discovery function has been lost.

By last year, Kuroda himself was expressing concerns about the moribund state of trading. “It has been pointed out that with a great narrowing of long-term yield movements, trade volumes are in a declining trend,” he said in July. He made those remarks after the BOJ board agreed to allow 10-year bond yields to fluctuate as much as 20 basis points either side of its targeted zero percent rate. The move, he said, “will improve the flexibility of yield price formation and ease some of the effects on market functioning.”

The central bank has also dramatically slowed the pace of its bond purchases, nowadays focusing on just keeping yields within their target zone. Partly because of its mammoth buying in the past, it doesn’t take much of an effort to prevent yields from rising. The annual pace of purchases was running at about 25 trillion yen as of mid-February, much less than half the official objective. That’s still enough to cover the bulk of the 33 trillion yen in new JGBs that the Ministry of Finance plans to issue for the 2019 fiscal year.

Even so, trading volumes remain subdued. In 2017, according to minutes of one meeting with the BOJ, industry representatives said that unless things changed, a large share of players will be so young that they will “have never seen the JGB market being volatile.” Even after the 2018 adjustments, a group of more than 60 market participants warned, some market orders just couldn’t be executed. Kato, the ex-Goldman economist, says the lack of veteran dealers and depressed trading volumes mean there would be “huge turmoil” if the bank ever shifted to tighten policy.

One trader who saw the writing on the wall was Xinyi Lu. Originally from China, he studied in Japan in the 1980s. In 1994, drawing on his advanced studies in options pricing at the University of Chicago, he jumped into the Japanese bond market with a job at Credit Suisse First Boston. Back then, 10-year JGBs yielded substantially more than those with shorter terms, and Lu would devise trading strategies by analyzing the structure of the yield curve. “People were very dynamic and took on risk,” he says.

By 1999 he reckoned he needed to switch focus. Amid deepening financial and economic woes, the central bank had lowered its benchmark rate to near zero. Believing the policy “would continue forever,” Lu concluded that Japanese companies just didn’t have the appetite to ramp up borrowing as they once had. The JGB market, he remembers thinking, “was dead, and there was no chance for it to come back.”

By the following year, he’d moved on to a job at Tokai Bank, focusing more on U.S. Treasuries. Despite all the misgivings about today’s policies, Lu says the example of the 1930s failure to cut off BOJ funding of the national debt still looms large, and he predicts that the stimulus will be similarly difficult to curtail because of political pressure.

Montgomery, who’s held visiting research positions at the BOJ and the Federal Reserve, worries about more than the upending of the bond industry. She and Ulrich Volz, an economist at SOAS University of London, sifted through 15 years of data from more than 100 banks before concluding in a paper presented to the American Economic Association annual meeting in January that prolonged BOJ stimulus has had only a “quantitatively small” impact on boosting bank lending. Worse, they reported, “the lending stimulated by providing banks with higher liquidity was mostly lending by sick, undercapitalized banks.”

In time, Montgomery says, there will be consolidation among smaller lenders. “We’ll see a lot of problems with the regional banks—maybe something extreme like failures, maybe mergers where healthier banks are pressured or encouraged” to take on their debilitated counterparts. Japan’s Financial Services Agency is increasingly concerned; it’s stepping up scrutiny of regional banks and plans stress tests as soon as this summer.

In addition, says Nagai, who’s now head of Japan economics at the research group Oxford Economics, “extremely low interest rates have contributed to the low rate of metabolism among businesses. Unprofitable companies have survived and are dragging each other down by causing stiff competition on prices.”

What’s more, wafer-thin returns have forced big investment funds to look outside of Japan. Japan Post, the big nationwide lender that likely owns a slice of Bond 350, has seen its holdings of JGBs tumble by 95 trillion yen from 2009 to 2018, according to records compiled by Michael Makdad, a Morningstar Inc. analyst in Tokyo; by contrast, the value of Japan Post’s stockpile of foreign bonds soared to 62 trillion yen from just 1 trillion yen during that period, even though those bonds incur foreign exchange risk unless the bank hedges its bets.

Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund, the world’s largest investor of its type, has also moved decisively away from JGBs since Abe took office and ushered in reflationary policies. Against this backdrop, it’s only natural that giant national banks such as Mizuho and Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Inc. would venture overseas in search of assets with higher returns. “These challenges for Japanese banks are structural and will continue as long as interest rates remain near zero,” Moody’s Investors Service Inc. said after the Mizuho mishap.

But don’t look for the stimulus policy to change anytime soon, says Makdad, who previously worked at Moody’s: “The bottom line is that the current situation can go on for a long time—as long as the global economy continues to expand marginally.” If the BOJ continues to buy bonds at the pace it did during the early months of this year, he says, it can probably keep the purchases going for another nine or 10 years, barring some major external shock. In the meantime, Kokusai-sensei will grow older and wiser, but he’s not likely to have much to do unless he’s tasked with a new challenge—like encouraging strong companies to invest more at home.

Anstey is managing editor for Asia cross assets at Bloomberg in Tokyo. Takeo and Fujioka cover the Japanese economy in Tokyo.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stryker McGuire at smcguire12@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.