Mexican Women Storm the Streets as Murder Toll Spikes

Mexican Women Storm the Streets as Murder Toll Spikes

(Bloomberg) -- Dozens of angry women tried to interrupt President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador’s press conference last month, shouting “not one more, not one more!”

Failing to get past his security brigade and into the National Palace, they spent hours outside, chanting and spray-painting messages -- “femicide state” and “they’re killing us” -- on the 500-year-old building’s walls. Finally, a select group was invited in to meet with one of the president’s top advisers, Leticia Ramirez Amaya, who runs the Office of Citizen Attention.

She listened politely to their concerns -- and, they said, told them she had no power to do anything about the scourge of violence against women in Mexico.

It was a disappointing and not entirely surprising response after months of street protests that have challenged Lopez Obrador’s commitment to human rights, said Rosalinda Penelope Pimentel, one of the demonstrators and a member of Frente Nacional Para la Sororidad.

“The authorities are stained with blood,” Pimentel said. “The people are no longer willing to be quiet.”

Simmering outrage over a culture activists have long condemned as demeaning to and endangering women has taken a new turn, threatening Lopez Obrador’s popularity. The latest surge came after the mutilated body of 25-year-old Ingrid Escamilla was discovered on February 9, and horrific photos of her corpse circulated on social media. A newspaper printed one on its front page under the headline, “It Was Cupid’s Fault,” stirring more fury over cavalier attitudes toward femicides.

A burgeoning protect-women movement has put the Lopez Obrador administration on the back foot. Three major newspapers and a top polling firm released recent surveys showing the president’s approval rating has fallen. It was 57% in a poll by El Universal, far below his all-time high of 79% one year ago. Among women, it was 53%.

That is hardly a no-confidence vote. But to the activists, it shows their message is, even if just on the margins, finally being heard.

“We’re getting to this level of outrage because, in spite of two decades of awareness of how severe violence against women has become in Mexico, there hasn’t been an effective response by the government at any level,” said Maureen Meyer, Mexico director at the Washington Office on Latin America, a think tank. “You still see widespread permissiveness within society of violence against women.”

The problems in a patriarchal society of discrimination and abuse surfaced prominently in 1993 in Ciudad Juarez, when the body of 13-year-old Alma Chavira Farel was found with signs of sexual attack and strangulation, introducing many to the term femicide for the first time. Chavira Farel’s uncle was arrested in the course of the investigation.

In 2006, then-President Vicente Fox notoriously referred to women as lavadoras de dos patas, or washing machines with legs, when commenting on how technological advances will free them from that household chore. Cat-calls and groping are so prevalent that buses and subways have dedicated cars for women and girls.

Jesus Cantu, information chief of Lopez Obrador’s press office, says his administration is is coordinating and assisting state governments where femicides are being investigated. “There’s a lot to do, but the performance of the authorities is improving,” Cantu says. “This is a feminist government.”

There’s been significant progress on a lot of the instances that had caught public attention and the government’s existing social programs will help women, Cantu added.

More than ever before, the federal government is under attack for what critics decry as its failure to beat back a wave of gender-based violence that affects seven in every 10 women, according to the United Nations.

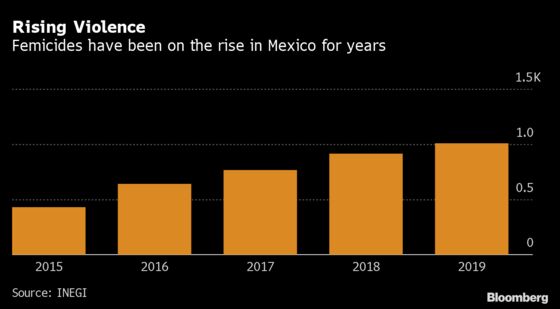

In fact, femicides have risen under Lopez Obrador’s watch, according to government statistics. More than 1,000 women were murdered in 2019, up from 912 the prior year and 426 in 2015. The explosion in gender-based violence is in line with a general increase in homicide rates, which have jumped 93% since 2015. In 2019, an average of about 100 people were killed every day.

Most homicides in Mexico aren’t investigated, and women in particular have few options when reporting crimes. They’re discouraged from pursuing legal complaints, and police stations -- which often are run by men -- lack important equipment, including rape kits.

On February 11, two days after Escamilla’s body was found, a 7-year-old named Fatima was kidnapped while waiting for her mother outside her school in Mexico City’s Tulyehualco neighborhood. Her body, showing signs of torture, was discovered less than three miles away inside a plastic bag.

Lopez Obrador was criticized for his response to questions about Fatima: He blamed neoliberalism -- a derisive reference to his predecessors -- and what he called “social decadence” for the security crisis he said Mexico faces.

Carla Rios, deputy director of advocacy group Marabunta, says his administration’s response to the femicide crisis has been tone-deaf.

“They need to listen to the victims and to the people protesting,” said Rios, who won’t venture outside Marabunta’s offices in Mexico City without first texting her whereabouts to a friend.

The women in the February 14 meeting with Ramirez Amaya included anarcho-feminists known for covering their faces with bandanas, students from Mexico’s national university and the mother and daughter of a woman named Diana who was murdered in the state of Mexico.

After their lack of success with the president, dozens of organizations are promoting a massive march on Sunday. They’re also calling on women to boycott work the next day. Mexico’s federal government and some of the country’s largest companies including Wal-Mart de Mexico SAB, Walmart’s local subsidiary, have promised no retribution against women who stay home.

Already, rumors of threats including physical violence and acid attacks against participants on Sunday’s march are circulating on social media. Protesters have been advised to take precautions.

Pimentel, a chemical engineer by training, took up the cause of women’s rights 30 years ago. Now she’s studying for a degree in law so that she can be more directly involved in individual cases.

Throughout the interview with her, she answered questions while texting furiously. About an hour in, she apologized and took a call from a woman seeking help, telling her to go straight to a police center colloquially known as the Bunker to file a complaint. Pimentel left the interview early to help her through the process.

“All the time, we’re dealing with emergencies,” she said before leaving. “We’re fighting for our lives. The thing about Ingrid Escamilla, the thing that was the most brutal and terrorist-like, is that we all lie in bed thinking that we could be next. Because that’s a reality in this country. Any one of us is a potential victim.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Justin Villamil in Mexico City at jvillamil18@bloomberg.net;Cyntia Barrera Diaz in Mexico City at cbarrerad@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Carolina Wilson at cwilson166@bloomberg.net, Anne Reifenberg, Melinda Grenier

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.