A Favorite Lyft Metric Is Messy

A Favorite Lyft Metric Is Messy

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As Lyft Inc. pitches itself to potential stock investors this month, it will stress numbers to show the improving financial profile of offering car rides. But one metric that Lyft — and Uber, most likely — will pitch is not as revealing as Lyft backers believe.

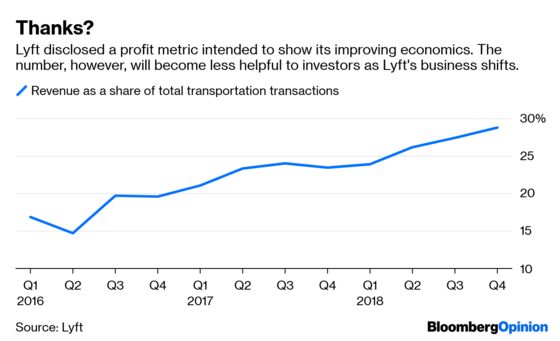

The metric is Lyft’s revenue as a share of the total value of car rides and other transactions. The figure, often called a “take rate,” is closely watched for companies that help connect buyers (passengers, in Lyft’s case) and sellers (drivers). Lyft disclosed the take rate last week among the key metrics for potential investors in its initial public offering. It’s meant to show that as Lyft grows, it’s taking a larger slug of money from drivers for each ride and paring financial incentives to keep drivers on the roads.

The more Lyft can control its driver economics, the more money it can keep for itself and the likelier the company is to become profitable at some point. This revenue as a share of total ride value was 28.7 percent in the fourth quarter compared with 19.6 percent at the same point two years earlier. To Lyft and its supporters, that’s a sign of improved financial efficiency.

This take-rate number, however, is not a clean evaluation of Lyft’s profit potential. That’s because the figure is getting — or will get in the near future — an artificial boost as Lyft generates more sales from bicycle rentals, electric scooter rides, flat fees from riders or organizations and car rentals to Lyft drivers. Those businesses other than single rides on demand muddy Lyft’s take rate, or what the company calls revenue as a percentage of “bookings” — the total value of transportation it facilitates.

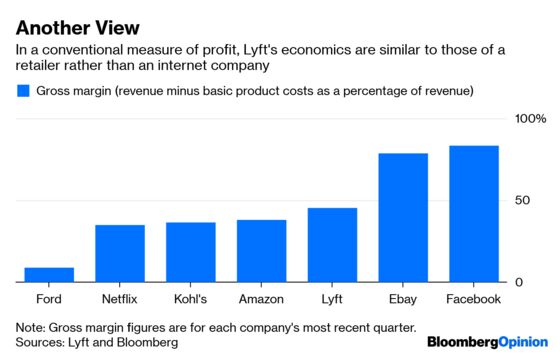

Here’s what I mean: When a Lyft driver completes a ride, he hands over fees and commissions to the company. The driver effectively holds on to the majority of each passenger’s fare, with Lyft taking the rest. Lyft records what it collects from the driver as revenue. If Lyft can boost the take rate, or the effective share it takes from each dollar of a ride, the company significantly improves its economics. That improved efficiency — potentially at the expense of drivers — is a big reason Lyft’s losses are ugly but not as ugly as they used to be. There’s big power in an improved take rate.

But in a growing number of cases, Lyft is recording the full value of what a customer pays as revenue. When it rents electric scooters, as it does in about a dozen U.S. cities, or bicycles through its recently acquired bike rental network, there is no driver with whom to share fees. When Lyft rents cars to drivers, it also records the full value as revenue. The take rate is also impacted by Lyft’s still nascent business of charging fees to doctors and other businesses that want to ensure their customers get to them.

As these businesses become a larger share of Lyft’s total transportation offerings, the take rate becomes less helpful for judging Lyft’s economics in its on-demand ride business. Uber Technologies Inc.’s take rate will most likely be even messier, if it decides to include it in its IPO documents. In short, it is getting tougher to judge whether Lyft and Uber’s core business is financially viable.

Lyft acknowledges the coming shift in the take rate. The company said its car rental program was responsible for 1 percentage point of improvement in its take rate in 2018, with better efficiency in driver incentives and higher fees and commissions from drivers responsible for the other 3 percentage points. Lyft said the impact of scooter and bike rentals was “not material” in 2018, but the company didn’t say whether the impact was significant in the fourth quarter, for example.

To be fair, this take rate has long been a messy number, and existing investors in Lyft and Uber know it. It’s not clear how much weight public investors will put on the take rate or bookings, another metric whose value will diminish over time.

Lyft’s IPO document also discloses figures such as the number of active riders and revenue per ride intended to highlight loyalty of riders and how much more they spend over time. Notably, though, those figures — and the take rate — are not that revealing on the all-important question of the financial health of the on-demand ride business.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shira Ovide is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. She previously was a reporter for the Wall Street Journal.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.