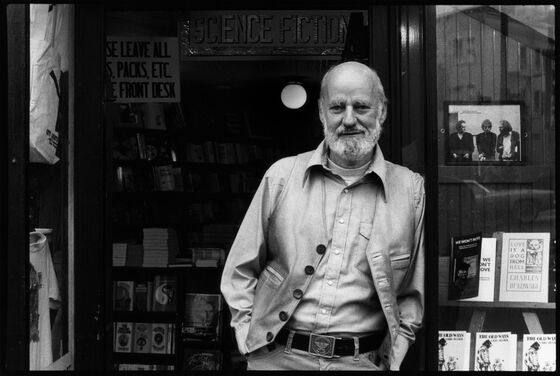

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Beat Poet, ‘Howl’ Publisher, Dies at 101

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Beat Poet, ‘Howl’ Publisher, Dies at 101

(Bloomberg) -- Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the poet and bookstore owner whose publication of Allen Ginsberg’s poem “Howl” in 1956 led to a landmark obscenity trial that spotlighted the Beat literary movement, has died. He was 101.

He died Monday at his home in San Francisco, according to the Washington Post, citing his son Lorenzo. The cause was lung disease.

Ferlinghetti’s City Lights became the nation’s first all-paperback bookstore when it opened in San Francisco’s North Beach section in 1953. Since then, it has served as a gathering place for writers, artists and bohemians, from Jack Kerouac and the Beats to hippies, punk rockers and iPhone-carrying hipsters.

He also wrote more than 30 books, including 1958’s “A Coney Island of the Mind”, a collection of poems that has sold more than 1 million copies. Fluent in French and Italian, Ferlinghetti translated poetry into English, wrote plays, art criticism and essays and was a talented painter. In 1998, he was named San Francisco’s first poet laureate. France awarded him the title of Commandeur des Arts et Lettres.

Ferlinghetti published “Howl and Other Poems” as part of City Lights’ fledgling Pocket Poet Series, printing 1,500 copies that sold for 75 cents each. U.S. Customs seized 500 books from a second printing, citing the poem’s “obscene” nature.

Obscenity Trial

“It is not the poet but what he observes which is revealed as obscene,” Ferlinghetti wrote in a column in the San Francisco Chronicle after the books were confiscated in early 1957.

Ten days after the column ran, the Collector of Customs released the books and the U.S. attorney dropped the matter. Still, San Francisco police arrested Ferlinghetti -- and local authorities brought obscenity charges against him.

In a much-publicized trial, defense witnesses including critic Kenneth Rexroth and author Mark Schorer, a professor at the University of California at Berkeley, testified to the book’s literary merits.

The trial resulted in a widely hailed decision against censorship. Judge Clayton W. Horn of San Francisco Municipal Court acquitted Ferlinghetti, declaring that “Howl” had redeeming social importance and was thus protected under the U.S. Constitution.

Banned Books

“Before ‘Howl,’ there were so many books that weren’t allowed in the U.S.,” Bill Morgan, author of a history of the beat generation, told the Newark Star-Ledger. “You had to sneak in copies of ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’ and ‘Lolita’ from Paris.”

By the trial’s end, more than 10,000 copies of “Howl” were in print.

Lawrence Ferling was born March 24, 1919, in Yonkers, New York, the youngest of five sons of Carlo and Clemence Ferling. At age 36, he changed his name to Ferlinghetti, the surname his father had shortened on arriving in the U.S. from Italy.

His childhood was turbulent. His father died before Lawrence was born and his mother, overcome by grief, suffered a breakdown and was placed in a state hospital.

Relatives of Lawrence’s mother, Ludwig and Emily Mendes-Monsanto, took him in when he was about a year old. Soon after, Emily left her husband and brought Lawrence with her to France, according to Ferlinghetti’s biographer, Neeli Cherkovksi. After returning to New York four years later, Emily took the youngster with her to Bronxville, New York, north of the city, where she’d been hired as a live-in French tutor to a wealthy family’s daughter. When Emily subsequently left, Ferlinghetti was raised by the family, Anna and Presley Bisland. He chose to stay with the Bislands when his mother, by then a virtual stranger, showed up.

Greenwich Village

Ferlinghetti attended high school at Mount Hermon, a boarding school near Greenfield, Massachusetts. He earned a journalism degree from the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill in 1941, then joined the U.S. Navy during World War II.

He lived in New York’s Greenwich Village while working on his master’s degree at Columbia University. It was there that his interest in poetry bloomed. He read William Carlos Williams and Marianne Moore and continued to buy any new work by his Village neighbors E.E. Cummings and Kenneth Patchen.

Ferlinghetti moved to Paris to obtain his Ph.D. at the Sorbonne and met his future wife, Selden Kirby-Smith, on a ship sailing to France from the U.S. in 1949. They were married two years later in Florida before settling in San Francisco.

Early Beats

City Lights, named after the 1931 Charlie Chaplin film, was originally a pop-culture journal published in a cramped space above a flower shop by Peter Martin, a transplanted New Yorker. When it folded, Martin told Ferlinghetti about his idea to open a book store specializing in paperbacks, which were then a new product. They each put up $500, and City Lights Books was born in June 1953.

“Once we opened the door,” Ferlinghetti said, “we couldn’t get it closed.”

Martin sold Ferlinghetti his interest and moved back to New York two years later. By then, Ferlinghetti had expanded the store’s scope to include the City Lights publishing imprint.

Ferlinghetti attended Ginsberg’s now-legendary reading of Howl at San Francisco’s Six Gallery on Oct. 7, 1955.

The audience erupted in cheers after listening to “Howl,” whose first line -- “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness” -- would become indelibly linked to the Beat Generation. The poem lashed out against what Ginsberg saw as the suffocating forces of materialism and cultural conformity.

‘Apocalyptic Message’

Ferlinghetti went home that night and typed a note to Ginsberg paraphrasing one that Ralph Waldo Emerson sent to Walt Whitman upon receiving a copy of the 1855 edition of “Leaves of Grass”: “I greet you at the beginning of a great career. When do I get the manuscript?”

“I knew the world had been waiting for this poem, for this apocalyptic message to be articulated,” Ferlinghetti wrote in 2006. “It was in the air, waiting to be captured in speech. The repressive, conformist, racist, homophobic world of the 1950s cried out for it.”

A year after “Howl,” City Lights published “Gasoline” a collection of poetry by Beat writer Gregory Corso. To his later regret, Ferlinghetti turned down an opportunity to publish Kerouac’s now-classic novel “On the Road,” though he did bring out his “Book of Dreams” in 1961.

Ferlinghetti continued to write poetry and operated City Lights for more than a half-century. In 2003, he was awarded the Robert Frost Memorial Medal and the Author’s Guild Lifetime Achievement Award.

He always tried to de-emphasize the term Beat Generation, a phrase coined by Kerouac, as a description of the San Francisco literary scene of the 1950s. He preferred to call it “an early phase of counter-culture poetry regeneration in America.”

Ferlinghetti and his wife, who were divorced, had two children: Julie and Lorenzo.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.