Kochs Downplay Politics to Find Common Ground in Liberal Silicon Valley

Kochs Downplay Politics to Find Common Ground in Liberal Silicon Valley

(Bloomberg) -- Last year at Base Camp, the sleepaway summer gathering hosted by venerated venture firm Sequoia Capital, a surprise guest greeted the assembled entrepreneurs—Charles Koch, the chief executive officer of Wichita, Kansas-based Koch Industries Inc.

Dressed casually in blue jeans and a maroon button-down shirt, Koch sat under a large canvas tent alongside Stripe Inc.’s Patrick Collison. He spoke to the crowd of tech elites, gathered at Base Camp to hear talks by day and sing campfire songs by night, and espoused the virtues of empowering employees and building a good corporate culture, according to multiple people who were present. All of the people asked not to be identified because what happens at Base Camp is intended to stay at Base Camp.

The famous libertarian industrialist’s appearance at a whimsical retreat in the liberal stronghold of Silicon Valley seems incongruous. But it’s just one example of the inroads the Kochs have made into the startup ecosystem. The appearance was brokered by famed Sequoia investor Mike Moritz, who knows Charles Koch, as do VCs Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz, as well as Wilson Sonsini founding partner Larry Sonsini. Koch even recently taped a segment on entrepreneur Tim Ferriss’s podcast. All those connections have helped along Koch Industries’ most ambitious foray yet into the world of tech, the conglomerate’s corporate venture fund, Koch Disruptive Technologies.

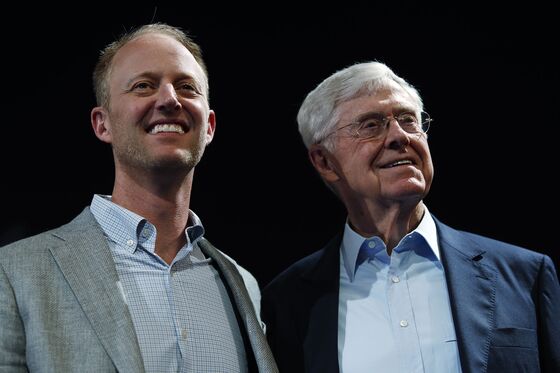

As the wider company reckons with the tech revolution, Koch Disruptive Technologies is focused primarily on startups that can work with existing Koch companies, or help Koch Industries itself build out its tech portfolio. The fund’s president is Chase Koch, Charles’s son and the rising star of the business, who is widely assumed to be heir apparent to the Koch empire. In recent years, Chase has been stepping up media appearances, usually of a less overtly political nature than the older generation of Kochs have become known for. That nonpartisan approachability, plus his and Charles’ work stoking Valley good will, has helped Koch Industries build up enough credibility to allow the conglomerate to pour about $500 million into startups over the last two years.

Now, though, as the presidential election season is bringing politics back into high focus, fresh concerns over the Kochs’ history of prolific political giving could dampen the fund’s momentum. The recent death of Charles’s brother, David, who was especially politically involved, has refocused attention on that history. Hobnobbing at parties, learning about hot companies and wooing founders could become difficult for the Koch-linked fund, particularly as 2020 candidates ratchet up their anti-tech rhetoric, drawing an industry that has long yearned to distance itself from Beltway drama increasingly into the scrum.

Over the decades, the Koch family has contributed tens of millions of dollars to mostly conservative political causes, becoming a force in American politics. Charles and David Koch backed a variety of think-tanks, candidates and organizations, including the deep-pocketed advocacy group Americans for Prosperity.

“There are certainly preconceived notions of Koch,” said Jason Illian, managing director of Koch Disruptive Technogies. But in most meetings with entrepreneurs, said Illian, “They’ll say, ‘Tell us what you’re about.’”

A former entrepreneur himself, Illian has followed an unusual career path. In 2005 he appeared on the Bachelorette, which prompted him to author a book of romantic advice called Undressed: The Naked Truth About Love, Sex, and Dating in 2006. He wrote another in 2007, called MySpace, MyKids: A Parent’s Guide to Protecting your Kids and Navigating MySpace.com. Then, after a stint running the media company behind Godtube.com, in 2010 Illian founded BookShout, a Dallas-based ebook distributor. He got to know a Koch executive years ago via investing circles in Dallas, and the fact that his wife comes from Wichita helped him cement ties with the company, including Chase Koch.

Illian said he emphasizes areas where he believes he can find common ground in the Valley. For example, there’s Charles Koch’s work for criminal justice reform, which is also a pet cause for organizations such as Alphabet Inc.’s Google.org and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. And like most of California, the Kochs did not support the election of Donald Trump. The industry also has its own well-documented libertarian streak, often bucking what it sees as onerous government regulation, a viewpoint that jibes with the Kochs’ famously anti-regulation leanings.

That leaves plenty of room for controversy. For example, the Kochs have worked against environmental legislation aimed at combating climate change, a popular cause in Silicon Valley. The Koch network also opposed the expansion of health insurance in 2010’s Affordable Care Act and acted as a vocal critic of President Barack Obama, who was popular in California. Meanwhile, Americans For Prosperity also supported the confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who came under fire over sexual assault allegations made by psychologist Christine Blasey Ford, who teaches at Stanford University.

David Vogel, a professor of business ethics at the University of California, Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, said it wouldn’t be unreasonable for a startup to think twice about taking funds from any group whose hallmark positions the startup and its founders eschew. “If you’re concerned they use their resources in ways you disagree with, if your company does well, you’ll be contributing more to those resources,” he said.

Illian said he wants political differences not to be a deal breaker. “We’re not asking everybody to agree with us on every topic,” he said. “We just want to build relationships.”

The seeds for Koch Disruptive Technologies were planted at a fertilizer conference attended by Chase Koch. Amol Deshpande, the CEO of venture-backed Farmer’s Business Network Inc., hit it off with Chase, who was then running Koch Agronomic Services. The younger Koch invited Deshpande to visit Wichita in early 2017, according to spokesman Rob Carlton.

In Wichita, Deshpande emphasized the strategic insights and benefits that startups could gain from Koch Industries, whose businesses include consumer packaged goods like Brawny paper towels and Dixie cups, as well as a sprawling portfolio of refineries, cattle ranches and electronic component makers, with an estimated combined revenue at $110 billion last year. Galvanized by his conversation with Deshpande, Chase pushed the Koch machinery into action. The venture fund launched later that year.

The Kochs “don’t get enough credit for their entrepreneurial mentality, probably because of where they’re situated, and some of the connotations with the name,” Deshpande said. When asked, he clarified that by “connotations,” he meant politics.

But with the elevation of Chase, those connotations could shift. The younger Koch told Politico last year that politics is “not at all what I’m passionate about.” In public appearances, the younger Koch has focused less on supporting Republicans, and more on anti-poverty programs. At the same time, the Koch-backed Americans for Prosperity has said it would seek more “nonpartisan solutions.”

In meetings in the Valley, Joe Lonsdale, an investor and co-founder of Palantir Technologies Inc., said Chase Koch appears “eager to avoid controversy and to work on innovation and philanthropy in ways that are non-partisan.” Lonsdale hosted the first major meeting for the younger Koch at his home, gathering a group of tech investors and entrepreneurs for dinner. It would become one of a series of dinners thrown for Chase Koch around Silicon Valley.

“I went into that with, admittedly, probably a closed mindset,” Chase said of one of the mixers, according to an account told to CNBC. He was thinking, “How are they going to view Koch? How are they going to view me? Are they going to be open? And I was blown away.”

Koch Disruptive Technologies, or KDT, made its first startup investment in late 2017, leading a $150 million round into Insightec, an incision-less surgery startup based in Miami and Israel. “What Koch came to us with is ‘Look, we’re not just about money,’” said Insightec CEO Maurice Ferre. “They opened doors for us and helped us build our business.” For example, Ferre said he’s consulted more than once with experts at various Koch companies, including Molex, an electronic-component company, which gave advice even before the investment. The Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology also helped connect Insightec with a handful of hospitals around the country that might buy its tools for treating Parkinson’s tremors and other afflictions.

The following year, KDT led a $125 million round into a software company called D2iQ, after being introduced to the startup by Andreessen Horowitz, a previous investor. In January, it led a $160 million round into 3D-printing company Desktop Metal, which also now works with Koch businesses like equipment-maker John Zink Hamworthy Combustion. And in August the fund put an undisclosed amount of money into a mobile rewards service called Ibotta.

None of the companies report any negative fallout as a result of their investor’s political connections. “I’ve never been in an awkward situation where someone has come up to me and said, ‘You’ve taken Koch money,’” Insightec CEO Ferre said. CEO of D2iQ Michael Fey said, “It doesn’t come up with my employees. It doesn’t come up with my recruits.” Besides, he added, “trying to attach values to the source of the money is difficult to do.” The sources of the cash behind even traditional venture funds—like pension funds, endowments or Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds—are often not made public.

Ric Fulop, CEO of Desktop Metal, said he welcomed the Koch’s controversial viewpoints, regardless of whether he agrees with them. Fulop grew up in Venezuela, and said he saw political leaders there stamp out opposition to the detriment of the economy. “We need to go to a world where everybody’s entitled to their own opinions,” he said.

As questions over the source of big tech’s funding become more relevant, particularly after controversies surrounding Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, some in tech believe it’s increasingly important for companies to consider who their investors are when the information is available. "It is much more dangerous to be unaware of whom you're taking money from, and what kind of politics they support," said Kellie McElhaney, a University of California, Berkeley professor. And while complete alignment with an investor may not be possible, "you sure as heck should have some core values you're not going to compromise on."

The question of taking the Kochs’ money did come up for Ibotta CEO Bryan Leach, who was introduced to Koch Industries through the high-powered tech lawyer Larry Sonsini. Leach, who identifies as a progressive, said he was asked about the Koch investment during a recent staff meeting at the mobile rewards company. “We don’t have an ideological litmus test for people who can use our product,” he told employees. “Nor do we have an ideological litmus test for who works at our company.” A grateful conservative employee in the audience came up and thanked him afterward, he said.

Yet as Koch Industries moves deeper into the world of tech, not everyone is comfortable with the association. Data and satellite imagery startup Descartes Labs employs many climate scientists and others who hold differing views to Charles Koch on how to combat climate change. So when the company started working with Koch Industries a few years ago, CEO Mark Johnson said it led to “vigorous debates” over the connection. Though he added that the same vigorous debates take place over other clients, such as the Department of Defense.

“We work with these companies who are industrial companies because we want to be inside the tent,” Johnson said. “We want to help them be better stewards of the environment.” Descartes is still doing business with Koch Industries, and continuing the debates.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Anne VanderMey at avandermey@bloomberg.net, Emily Biuso

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.